When it comes to university executive pay, civil society expects increased levels of transparency and accountability from both the public and private sector, regardless of where the revenue is sourced from.

Government expects reasonableness and fairness. However, what is perceived as “reasonable” depends on several factors including political ideology. There is also the relative role that a public funded university plays with other institutions such as health trusts and local councils in communities and the effect this has on perceptions of executive pay.

Equally, universities are considered centres of truth that society relies upon. This can create an expectation of higher levels of integrity, fairness and transparency when it comes to the way they behave and reward, including executive remuneration.

Unfortunately, evidence seems to suggest that higher education is dragging its feet

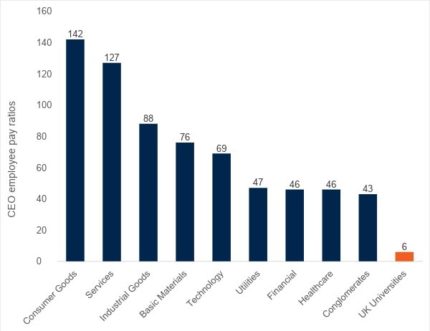

As Wonkhe has covered elsewhere, executive pay in UK higher education has been a point of tension for at least the past 25 years. In fact, this has been an issue across many sectors and it would appear for good reason. Figure 1 highlights the pay disparity between a CEO and the average staff member across a range of sectors.

Figure 1 | Average ratios of CEO pay to staff pay package, by industry sector

Taking this a step further, the High Pay Centre (2018) found that for every £1 the average FTSE 100 employee is paid, their CEO receives £145. This is higher than last year (128:1 in 2016 or 146:1 in 2015), but in a different stratosphere when compared with the £45 they would have received 25 years ago. No wonder the average punter feels aggrieved.

Higher education is not immune from this debate. There are repeated articles in the media and statements by politicians about higher education executive pay.

A signal of value

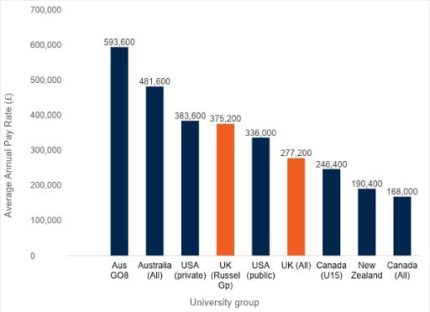

UK higher education commentators, media and politicians all frame remuneration from a point of view of cost (i.e. they are paid too much). Figure 2 provides a comparator of vice chancellor pay across multiple countries and institutional forms.

Figure 2 | Higher education vice chancellor pay

While it may be difficult to draw too many conclusions from this data, the surprising element that comes out is that the UK maybe doesn’t “overpay” its most senior executives relative to others. It is comparable to pay levels for similar roles in Canada and the USA. The anomalies here are the Australian universities, particularly Group of 8 institutions.

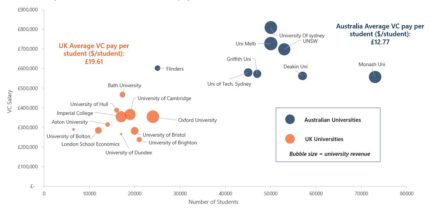

Further analysis between the UK and Australia paints an even more intriguing picture of executive salaries. Figure 3 analyses the ratio between the size of the student body verse the vice chancellor’s pay.

Figure 3 | Analysis of student numbers vs vice chancellor pay

What emerges here is that in both jurisdictions, there is higher pay in general for institutions that have larger student bodies. Research from the University of Kent also appears to show that the smaller institutions follow the larger ones on executive pay.

Different lenses give perspective

Setting the right executive pay (and managing the performance expectations that befit the pay) is a contested domain. The OfS recently stated that higher education executives should be paid less year on year seems narrow in view as does the converse argument of “you get what you pay for.”

If there is a real story, then it should be one where greater maturity is required by both the sector and the OfS. Institutions must do a better job at articulating the rationale for executive pay including pay rises and payouts, and genuinely engaging the community is this discussion in a language that the community appreciates.

In the end, there has been too much commentary on the topic and too simplistic a response by the regulator and the sector. It’s time to properly work through the issues together and to co-create an approach that moves beyond single points of view to one that garners respect from all parties.

Select an independent head (probably with an ethics background) to review and recommend an approach to executive pay in higher education, Spend time listening and really understanding the different lenses. Hold proper co-design sessions with diverse stakeholders that are expertly facilitated. Use data and see what other regulated industries are doing around the world. Put out discussion papers. Be bold with the possible.

Frankly, we can all do better than where we are today and have been for the past 25 years.

I think it is quite problematic to compare universities with profit-making corporations. Universities aren’t real businesses – especially when most of the income comes from government (albeit indirectly). Universities’ success is not measured by profit. This is apples and pears. there is also evidence that this habit of benchmarking is what is fueling the inexorable and entirely unjustifiable hikes in VC pay.

The only really shocking thing is that no-one ever seems to ask these questions of Australia.

This is just nonsense from start to finish. Try comparing UK VCs’ pay with their equivalents in European publicly funded universities and you will see that they are much more generously remunerated, in general. Secondly, in the UK academic salaries in general have been hugely held down by below-inflation pay rises for years and years now. Why should so-called ‘executives’ be immune from this trend? Thirdly, academic leadership and university leadership should have nothing to do with being compared to the private sector. Higher education is a public service/public good, academics are public servants, and we need a much more… Read more »

I agree with both previous comments. The very notion of “executive pay” or the concept of a “CEO” in a university context smacks of unthinking philistinism (which unfortunately has dominated the public debate and policy making in the Anglophone world for far too long). Yes, most universities in the UK are private incorporated organisations with a charter etc. Yet they are also non-profit and quasi-public organisations due to their purpose, funding and regulatory context. Governance structures and logics imported/adopted from the for-profit sector (and here the model of the widely held company) are at odds with the aforementioned. Instead of… Read more »