For a long time, when immigration numbers were rising and Conservative ministers were having account for that, they argued something quite simple.

Yes – but we’re in control of who’s coming now. Us. Not those Eurocrats.

As such, despite the mixture of naivety and performative bafflement swirling its way around the sector at the increasingly tightening student immigration regime, what’s happening now was inevitable.

Because ministers don’t look in control – and that’s worse when pretty much all that’s left of the Conservative Party in government are those that campaigned to take it back.

And before you get excited at the prospect of an election, what is Labour Shadow Yvette Cooper’s go-to line on the government when it comes to immigration? That it has “lost control” of the immigration system.

It’s why arguments that explain the economic, social or cultural contribution made by international students are likely to continue to fall on deaf ministerial ears.

The important question is therefore to ask how that happened – and what might be put in place to reassure future ministers that any reversals to restrictions won’t cause a similar problem in the future.

A buccaneering trading nation

If we take ourselves back to 2019, Boris Boosterism and tales of trade filled many a Number 10 press release. In the early days of Brexit it was crucial to send signals – both home and abroad – that Britain was open for business and poised for a slew of scientific and technological breakthroughs.

You could see it all in the announcement that ushered in the Graduate Route visa. Yes, the stated idea was that talented international students would be able to build successful careers in the UK – but that was justified on the basis that half of all full-time postgraduate students at the time were studying Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths (STEM) subjects:

This will build on government action to help recruit and retain the best and brightest global talent, but also open up opportunities for future breakthroughs in science, technology and research and other world-leading work that international talent brings to the UK.

The problem is that this isn’t what has happened. Hundreds of thousands of students studying social care and business studies is what happened. Yet even that might not have mattered but for the pace of expansion that then ensued.

When then Trade Secretary Liam Fox – a notable “out” campaigner – had launched the International Education Strategy in March of that year, he said it was “more critical than ever” to build on the UK’s position as a world leader in education and trade. International students were crucial exports:

Our education institutions are among the world’s best. We have four universities in the top ten globally, so it’s no surprise that the UK is the second most popular study destination in the world for international tertiary students, with more than 440,000 higher education students from abroad choosing to study here.

Our ambition is to grow the value of education exports to £35bn by 2030 – an increase of 75 per cent. That is why today we’re also announcing our ambition to increase the number of international students choosing the UK as a study destination for higher education to 600,000 per year by 2030.

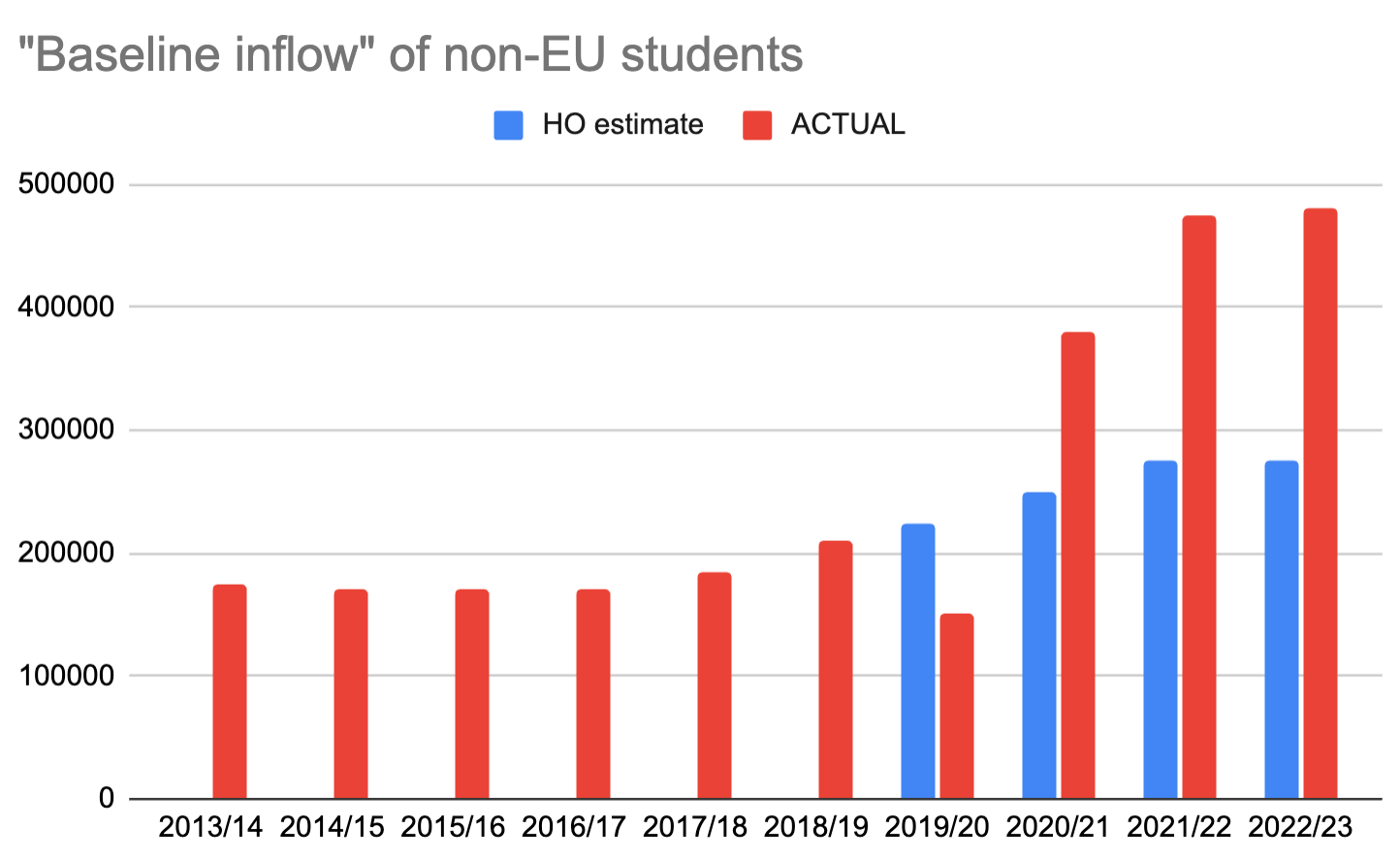

But that isn’t what happened either. Given the immigration part of the political consensus at the time, anyone that thinks that hitting that target the best part of a decade early – wrecking the modelling carried out by the Home Office in 2019 – was good news is again either being naive or performatively ignorant of the politics of government.

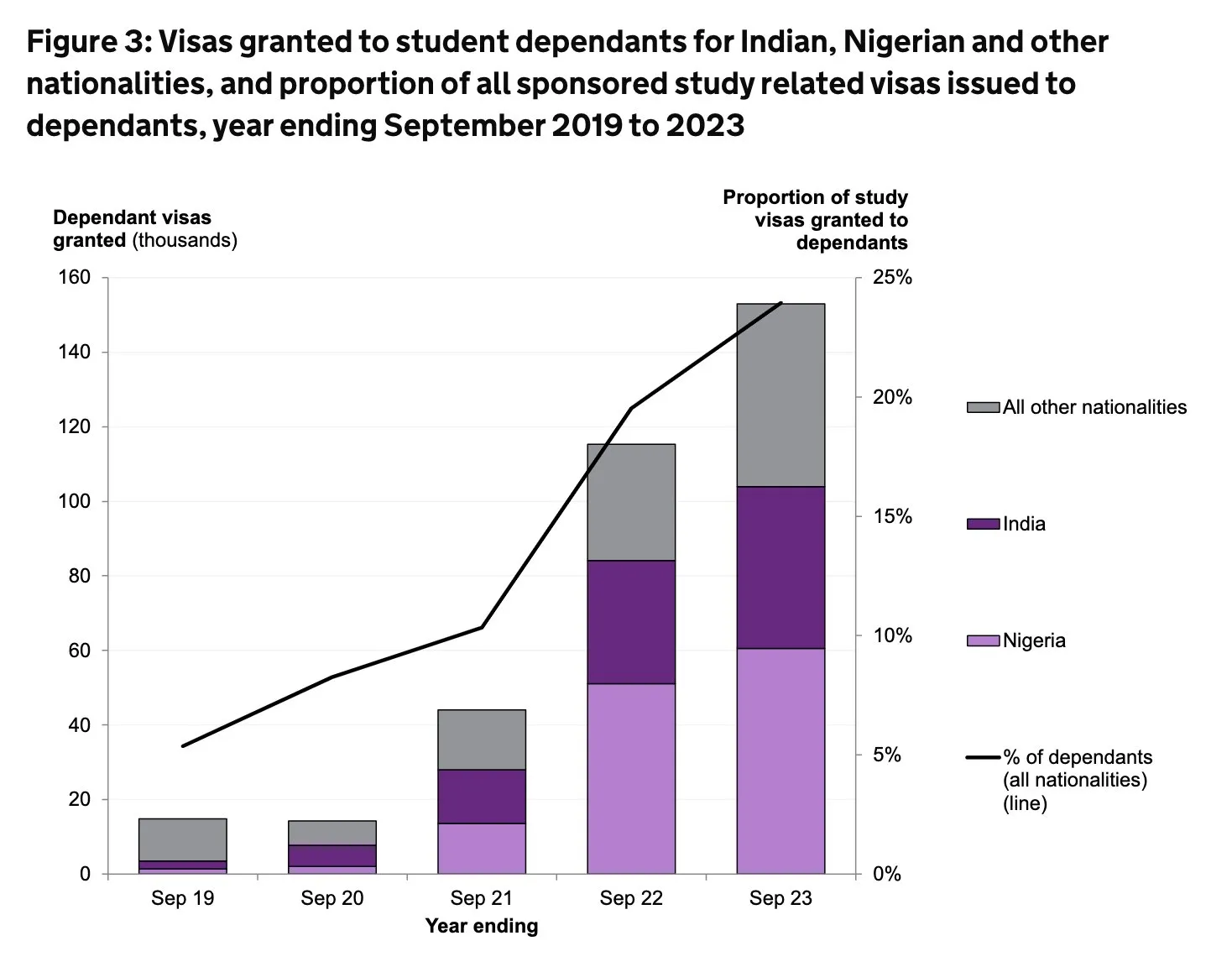

Then add dependants – barely mentioned in the impact assessment, never anticipated, and so not modelled for impacts.

Then add dependants – barely mentioned in the impact assessment, never anticipated, and so not modelled for impacts.

In other words AY 2022/23 closed out at about 360k visas issued ahead of where the estimate was.

Graduate route takeup has been about 1 in 4, which isn’t far off what they guessed – but it’s a quarter of a much bigger figure than they thought, and itself has a compound impact on temporary population growth.

Growth that nobody ever agreed to.

Widening the net

Despite the pervasiveness of the argument to take international students out of figures that calculate it, this isn’t really about “net migration”.

Even if every international student left after completing their degree and/or the graduate route, adding the best part of a million people to the UK’s cities and university towns over three years required and requires both institutional and community infrastructure that nobody appears to have been willing to take responsibility for planning or securing.

If we view international students as a kind of educational tourism, it would be like staging the Eurovision in a city with no hotels. Everyone would be late to the event, prices would rocket, locals would be furious at not being able to get on the metro, and so on. Waiting for the market to respond with capacity is too slow – and basically immoral.

The Home Office impact assessment did some stuff on the regional location of where graduates would end up – but nothing much on any impacts of very high growth itself. Population absorption – both logistically and politically – is straightforward when increases are modest and spread over time. It’s always a different story when it’s very high numbers very quickly.

As I’ve noted on here before, last December’s James Cleverly announcement of “the biggest ever cut to legal migration” only sounded like a lot against a backdrop of a rise of about 400k more student visas a year (100k ish of which stay on on the grad route) in three years.

That was likely not far off the biggest ever increase in legal temporary migration – a position that was unlikely to have survived unscathed under a government whose manifestos kept promising lower numbers.

And it’s true that for the Department for Education (DfE) and the Treasury, this has all enabled home domiciled fees to be frozen without, until now, causing a huge amount of pain.

But I suspect people overestimate the extent to which there’s a grand plan in there anywhere – instead, it’s almost certainly been much more likely to be chaotic decision making lurching from pressure point to point, without anyone stepping back to determine any kind of “plan”.

The blame game

We could try to work out the answer to the question of who’s to “blame” for the estimate being so out – but we really should also ask how, once the lines on the growth started to spike, they let growth get so big so fast without taking action until recently.

The first problem is the mixture of reputation lag, data lag and compound expansion impacts that characterise our understanding of student numbers.

By reputation lag, I mean that even if international students are having a rotten time now, reputation reasons prevent the sector from either finding out or admitting it until it’s much later. Hence strong demand plus research performance is misread as excellence, at least for a while.

When growth is steady and slow, HESA stats are a useful guide to what’s going on. When it rockets up in the way that it did, heavily lagged HESA data, plus visa issuance data (which masks the way the total here is totting up via the graduate route and switches to skilled routes) eventually make it look like ministers and the public were being lied to.

Internally in the Home Office, the immigration rules were always supposed to offer a kind of brake. There have never been caps on subjects – perhaps because officials and ministers simply believed that it was STEM that would grow – but at least there were rules that assured course quality, immigration compliance and a consideration of infrastructure implications when issuing Confirmation of Acceptance for Studies (CAS) numbers.

Course quality – carried out officially by the Office for Students (OfS) in England and the QAA elsewhere – has proved to be a disaster because neither of the systems have proved able to operate in a rapid growth scenario. Both are themselves systems instead designed for gentle growth – with OfS in particular dependent on lagged indicators to even trigger, let alone apparently languidly inspect, “poor” provision.

Immigration compliance is interesting because all of the original announcements reference it – making much of the “highly trusted” sponsor status of universities that were to be doing the recruitment. Whatever “abuses” the Migration Advisory Committee are poised to assert exist in the current system will almost certainly be a mixture of things that only like look abuses when they’re at the scale we’ve seen, and things that UKVI will have had to admit that it didn’t see coming – hence pressure to shut the stable door now.

The infrastructure implications thing is especially odd. The immigration rules have said throughout that providers can apply for an increase in CAS allocation of up to 50 per cent of the previous year’s allocation – and that if the request would increase the current student body by 20 per cent or more, the request may trigger an Educational Oversight inspection.

It’s never been clear whether that 20 per cent was of the whole student body or the international student body – but either way, at least in England, the quality regime just isn’t set up for and hasn’t resulted in “receiving a report from your Educational Oversight body” even if UKVI wanted one, unless OfS has just written back and said “well, they’re still on the register”.

The misjudgement over the positive impact that the Graduate Route would have on demand – coupled with a post-pandemic spike in desire to travel and the stars aligning on currency comparisons between a weak pound and historically good numbers in the global south – then arguably also led to nobody thinking about the incentives problem.

Very few actors in the system are held back from recruitment on the basis of the restraints that are supposed to be there. OfS is too slow, consumer protection law doesn’t work in this space, the Advertising Standards Agency isn’t watching influencers’ YouTube videos, the Agent Quality Framework isn’t working and the people that think that external examiners or the reassuring bureaucracy of supposed entry requirements can withstand a need to keep the money flowing once you become dependent on it need a lie down.

Like sweeties

Aside from quality, though, the immigration rules have also said that when considering any request to renew (or by association, increase) the annual CAS allocation, it would take a number of factors into account, including but not limited to:

- Agents that used to recruit international students, where they have been linked to immigration abuse in the past

- The number, type and level of courses provided

- The student-teacher ratio in classes for the courses

- The number of students currently studying at the organisation

- The number of academic (teaching) staff employed on a full-time basis

- The total student capacity of the premises and any capacity restriction

Maybe it did take those things into account, or maybe its eye was off the ball. Maybe the list – which in full reads like it’s aimed at smaller providers with less of track record – looks at the wrong things. But either way, UKVI could have put the brakes on at any minute.

If its officials have been read the riot act over allowing numbers to grow so quickly, you can be sure that they’ll be doubling down on an over-correction – both in terms of the actions they can take regardless of the formal rules, and in terms of recommendations of changes to those rules. They allowed the boom – now they’ll be seeking to cause the bust.

Outside of what the Home Office has and hasn’t done, the Department for International Trade (DIT) won’t have being doing anything to signal to Universities UK or other sector bodies that doing anything other than topping up its even-harder to reach targets is brilliant stuff. And the Department for Education (DfE), whose priority has always been schools, will have been (and very much was) talking up international recruitment precisely because it’s been unable to get money or permission out of the Treasury to raise domestic fees even if it wanted to.

That then leaves universities themselves. I won’t repeat here my amazement that universities – who spend a lot of time defending their autonomy – have veered between suggesting that there is no quality or infrastructure problem with international PGT (when there self-evidently is), and pretending that they’ve had no control over the growth.

Whatever “deal” Gavin Williamson suggested he’d struck with Number 10, he’s long gone, leaving universities fatally exposed – because when you spend all day long saying you should be left alone to be responsible for something, you get the blame when numbers that look irresponsible need a fall guy.

So on the assumption that either instant, or at least delayed implementation bad news is coming, what should happen next?

No return to boom and bust

It’s not stupid to lobby Labour over the economic, social or cultural contribution that international students make – the mood music there has been better, after all – but it would miss the point.

In the grand scheme of things, the sector does sometimes suffer from “big number” syndrome – assuming that the figures that appear in reports make up more of a contribution to GDP than they really do. And given that so much of that “contribution” is in rent, it may not be the unbridled benefit to working people that we think it is.

Much more importantly, an Yvette Cooper keen to demonstrate that she is in control is going to want to know how any reversal to the crackdown, and subsequent increase, will be managed. And if I was in her team, I’d be raising eyebrows at promises from the sector, its regulator and a Department for Education that may not be winning arguments for fee increases.

When Cooper was last in government in the 2000s, the EU expanded significantly by adding ten new member states, primarily from Central and Eastern Europe. The UK, unlike most other member states, immediately allowed workers from these new EU countries access to its labour market.

That led to significantly higher than expected immigration numbers from these countries, particularly the “A8” – Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Migration was much greater than anticipated, with 129,000 migrants from A8 countries entering the UK in 2004 and 2005 alone.

That rapidity became a central issue in UK politics, intensifying debates over free movement and contributing to growing public and political dissatisfaction with the EU, culminating in the Brexit referendum decision in 2016.

The government had assumed that other member states would open their labour markets and so diffuse migration flows, and the decision was perceived and framed among the British political elite as a geopolitical matter rather than one focused on immigration.

Cooper will be wanting to avoid making the same mistakes for all sorts of reasons. And that’s why bleating on about the benefits of international students – even if a set of universities go to the wall – isn’t going to help. Explaining how expansion could be actually be managed this time around – educationally, regionally and in headline numbers terms – very much will.

That management of numbers could take many forms. You can see how it might be attractive for a Labour government keen on devolution to give the task of managed growth to the cities and regions – balancing their own housing and infrastructure needs with economic growth.

You can also see how international student immigration caps – of the sort currently rolling their way out around Canada – might look attractive in a context of relative positivity about benefits.

An alternative would be for the sector itself to manage the growth, either through its own restraint, or via one of the arm’s length bodies – although in the face of deepening funding problems, nobody is going to be thrusting their hand up to take that job (and blame/ire) on.

And instead of knee-jerk resisting any and every attempt at regulation (only to repeatedly have accept blunt versions of it when its assurances go sour), it really is time for the sector to propose regulation that works in a mass HE system – of agents, quality and expansion/capacity.

As we’re seeing and feeling now, higher education is a sector that is profoundly unsuited to rapid contraction. And if we’re honest, both for educational quality reasons and political reasons, it’s profoundly unsuited to rapid expansion too.

So there does need to be a restraint plan. Because if the sector wants to avoid another painful bust, it really needs to avoid another boom.

Great analysis of the blind spots in the policy-making and the repercussions. One blind spot that I feel hasn’t been recognised yet is with the product that the UK education establishment was selling…Master’s degree. These degrees were looking for a market as they have little value to most British industries and and inside joke in academia is that they are pretty much a ponzi scheme that needs to be propped up. However, the quality and impact of Master’s degrees hasn’t been questioned in this whole unraveling.