It was Philip Hammond’s first, and as it turns out, last Autumn Statement. The Chancellor really did follow through on his promise to streamline the UK government’s budgeting and economic policymaking by abolishing the Autumn Statement in favour of one annual Budget (to be held in Autumn). And so we say farewell to this tradition.

The idea was to move away from the hyperactive Osborne years when big changes came every six months. Although it doesn’t seem that the Chancellor held back too much this time, despite his distaste for the occasion. And as it turns out, universities and the research community will be significant winners from the new Chancellor’s largesse.

Deficit elimination, once again, has been delayed. Abandoning the old fiscal rules enabled the Treasury to dig out £23 billion over the next five years, despite the OBR’s significant downgrade in projections for growth and increased projection for inflation over 2017 and 2018. Tellingly, the OBR avoided any further radical new projections into 2019, an effective admissions that they have no idea which way the economy will turn as we approach the Article 50 ‘cliff edge’.

Out of the new £23 billion for the National Productivity Investment Fund (NPIF), £4.7 billion will go to science and innovation between 2017 and 2021. The extra annual spend will increase gradually year-by-year to £425 million in 2017-2018, £820 million in 2018-2019, £1.5 billion in 2019-2020, and finally an extra £2 billion in 2020-2021. Confounding some projections, this is real cash, funded by extra borrowing. Aside from housebuilding, it is the largest segment of new spending in NPIF, reflecting the sector’s success in ensuring that research is seen as a national investment and an effective use of government money.

The statement says that the new funding will be distributed by UK Research and Innovation, in line with the Chancellor’s aspiration not to be ‘prescriptive’, but it does highlight two particular areas where some cash will go:

Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund – a new cross-disciplinary fund to support collaborations between business and the UK’s science base, which will set identifiable challenges for UK researchers to tackle. The fund will be managed by Innovate UK and research councils. Modelled on the USA’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency programme the challenge fund will cover a broad range of technologies, to be decided by an evidence-based process.

Innovation, applied science and research – additional funding will be allocated to increase research capacity and business innovation, to further support the UK’s worldleading research base and to unlock its full potential. Once established, UKRI will award funding on the basis of national excellence and will include a substantial increase in grant funding through Innovate UK.

The last sentence sounds very much like an emphasis on QR funding via REF, but we shall wait and see. The government will also review the tax environment for R&D, and Science & Innovation Audits will continue. Much more detail will need to emerge before we can adequately assess the plans, but the early reaction from the science and research communities has been broadly positive.

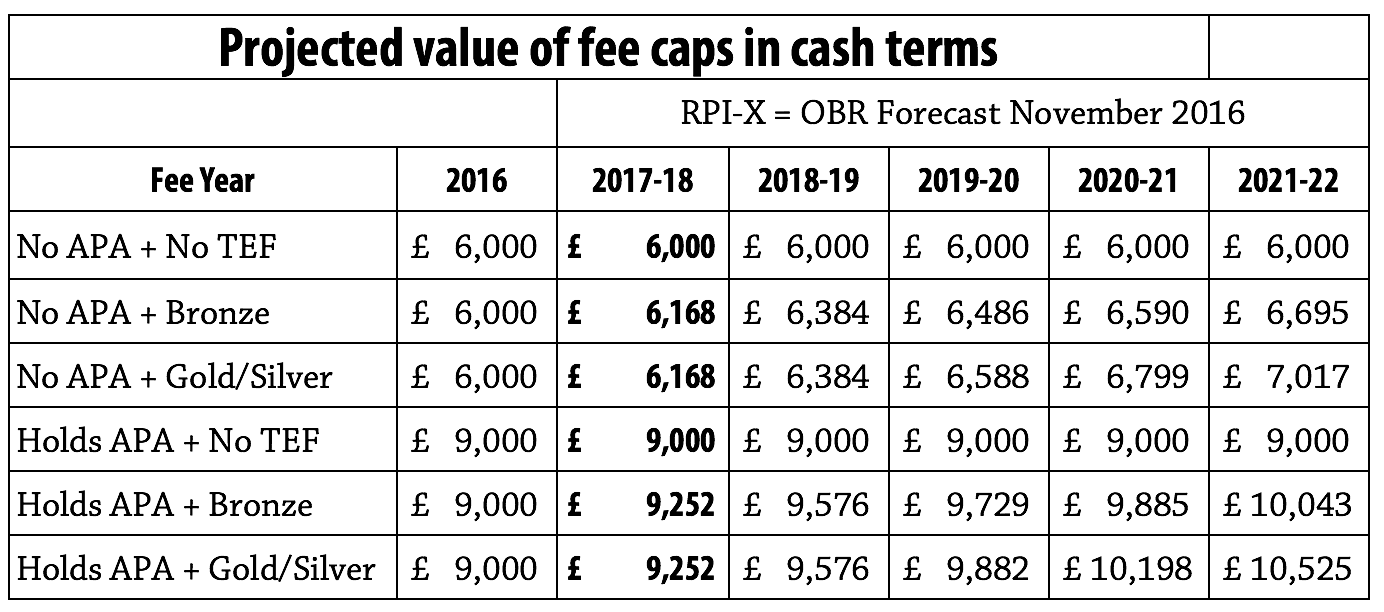

Beyond research and science, there are other interesting nuggets of news for higher education. Most notably, the difference between the OBR’s inflation forecasts for 2017-18 in March and now. A direct effect of Brexit and the depreciation in Sterling means that the 2.8% increase in tuition fees will no longer equate to RPI-X inflation. If today’s forecasts are correct, then fees will actually be £72 lower than they ‘should’ be.

This doesn’t sound like much, but multiply by 15,000 undergraduates in a university, and that’s a £1 million gap. The need to announce fee rises long before they are implemented based on relatively distant inflation projections will be a challenge going forward for future increases: if inflation is higher than expected, the sector will lose, but if it is lower than expected, the sector will win. With Brexit set to further hurt Sterling and the OBR reluctant to be too pessimistic in its forecasts (despite its ‘independence’), it is likely that the sector will more often lose, at least for the next few years.

We did a quick crunch of what the new forecasts actually look like for the fee levels in cash terms over the next few years, based on the 6 ‘caps’ that will exist in the system following the full roll-out of the TEF:

*APA = Access and Progression Agreement

We’ll be returning to this issue in more detail soon.

Elsewhere and along with deficit elimination, the sale of the student loan book has once again been pushed back. According to the OBR:

The process of preparing for the initial sale tranche continues, but we now judge the probability that the first sale will be completed in 2016-17 to be less than 50 per cent. We have assumed that the first sale will be completed in early 2017-18, but that the Government will still be able to complete the second sale by the end of 2017-18. Uncertainty over these timings and the rest of the sale programme remains.

Yet student loans are not only a headache to sell. The OBR’s forecasts also reflect how behaviour in relation to the loan book is now a significant aspect of consumer and household economic activity, as well as government finances. Student loan outlay will now be counted as a new form of household income, while student loan repayments will be counted as household spending. As loan outlays continue to increase, this might appear to inflate household incomes somewhat – as if the loan book needed any more political significance…

There were no significant adjustments to government department spending, announcements on new forms of student financing, or tweaks to the budgeting and accounting of the loan book – all developments that we got used to at such ‘fiscal events’ during the Osborne years. Departments will be left to get on with this themselves in the interim.

Hammond’s abandoning of Osborne’s old fiscal rules means that there is much more flexibility for the Chancellor during future budget announcements, something that will be needed if the Brexit car crashes violently.

The paradoxical impact of all this is that universities and researchers could continue to be big winners if Hammond continues to try and boost productivity and gets more relaxed about borrowing. That’s not the impact we were quite expecting from Brexit – whether it makes up for the real cost of leaving the EU remains to be seen.

I suspect much will be said about the census point for the rate of inflation that will apply to tuition fees – the sector finds itself in a similar position to train operators with regard to regulated fares with both students and institutions equally frustrated!

As an aside it will be interesting to see the effect of inflation on student living costs and whether this contributes to a change in student behaviour.