In these days of very public critique of universities, Brexit mayhem, and continued concerns about the impact of government immigration policies on students and staff, it is important not to forget about the key outward-looking aspect of higher education, represented by the various forms of Transnational Education (TNE).

There have been some big developments in TNE in recent which have emerged in several recent reports. Most notably UUK’s International Unit produced a detailed analysis in the Scale of UK higher education transnational education 2015-16 which includes regional trends drawn from HESA’s Aggregate Offshore Record (HESA AOR) data.

The overall finding is that over 700,000 students were studying for UK degrees outside the UK in 2015-16, which is 1.6 times the number of international students in the UK in the same year.

In brief, the UUK report describes the UK’s HE TNE provision in 2015 –16 as follows:

- 701,010 students were studying UK HE TNE programmes.

Excluding Oxford Brookes University, whose BSc in AppliedAccounting accounts for around 45% of these students

- 82% of UK universities delivered UK HE TNE.

- 23 UK universities hosted more than 5,000 TNE students, an increase from 18 in 2012.

- 82% of all TNE students attended these 23 universities.

- 65% of students were undergraduates and 35% were postgraduates.

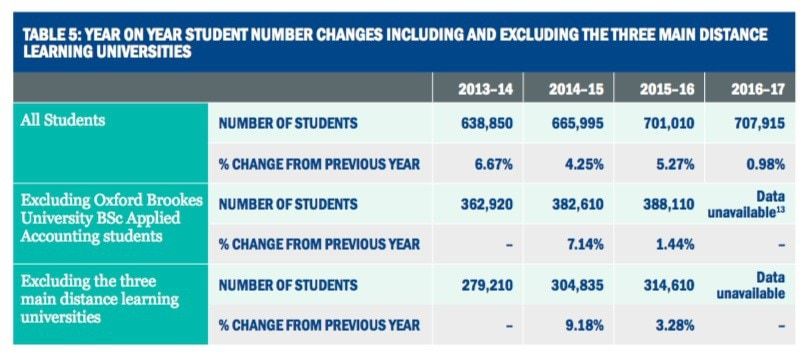

More details are in this table

The three main distance learning universities are Oxford Brookes, the Open University (OU) and University of London International Programme (UoLIP). Together they account for about 55% of TNE student numbers.

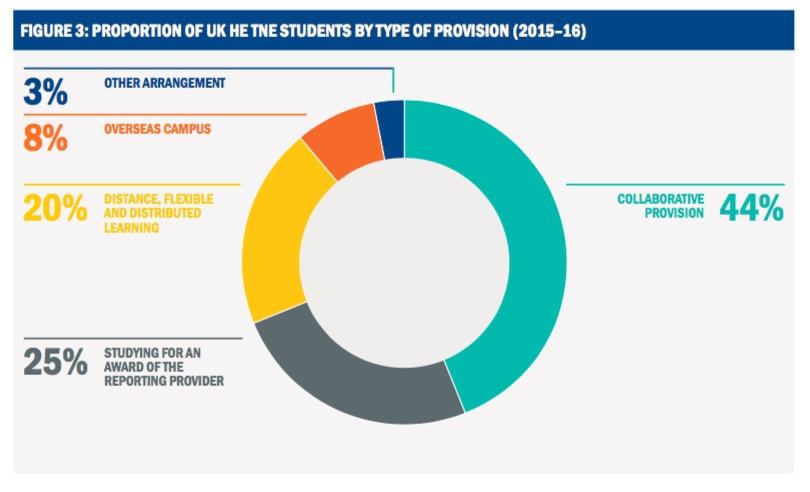

Looking more closely at the range of TNE types here (again excluding the three main distance learning universities):

But where are they all, I hear you ask. The main host countries for UK HE TNE students in 2015-16 are set out in the table below and, as can be seen from the list, the 10 countries hosting the highest numbers of students in 2015-16 were the same as in 2014-15, albeit with some minor changes of placings. In both years Malaysia and Singapore hosted the highest number of students (78,850 and 49,970 in 2015–16 respectively).

- South America had the highest average year on year growth from 2012-13 to 2015-16 (12.6%)although there was no change from 2013-14 to 2015-16. North America had the lowest (1.7%)year on year growth rate and saw a 0.8% decrease in student numbers from 2014-15 to 2015-16.Student numbers fell by 5% in non-EU Europe over the same period.

The branch campus dimension of TNE

I’ve written here before on branch campuses and, although they only account for a relatively modest percentage of student numbers as identified above, they are nevertheless significant in terms of in-country impact, as this post notes.

A report last year from the Observatory on Borderless Higher Education (OBHE) comments on the success factors which feature in a genuinely mature international branch campus or IBC. The report examines institutional integration and leadership, host country support and resources, regulatory environment and academics, and student experience to reveal what elements have proven influential in sustaining some IBCs for an extended period.

A few of the more significant ones:

- Support and integration. In all cases, the IBC has strong support from the highest levels of the university and is integrated into the academic and administrative functions of the institution.

- Collaborative leadership. There is a close relationship between home and branch campus leaders with constant contact between the two. Decision-making is often a collaborative process with some IBC autonomy.

- Evolving Relationship. The relationship with the local partner and/or government of the host country evolves over time.

- Finances and Resources. The focus of the home and branch is on quality over profit.

- Cooperation with regulators. Leaders of mature campuses emphasize the importance of having positive working relationships with local regulators and complying with local regulations.

- Research. If conducted, research is a function of the needs and capabilities of local, regional, and national contexts. There is active collaboration between the parent and branch campuses that do research.

- Replication. Institutions ensure that consistent academic practices exist at the home campus and all IBCs.

- Student mobility. While student mobility between institutional sites is usually a pillar of IBC strategy, it is not always as active as desired and is often skewed in one direction.

These, and many of the other points made in the report feel about right to me.

Whilst the University of Nottingham has been a trailblazer in IBC development and was the first Sino-foreign campus to open in China, the University of Liverpool, which opened its joint university with Xi’an Jiaotong University, XJTLU, shortly after the University of Nottingham Ningbo China, now has the largest IBC in China. University World News has reported though of plans to expand XJTLU further with the addition of a second campus:

The plans for the new campus were unveiled as May visited China accompanied by University of Liverpool Vice-Chancellor, Professor Dame Janet Beer. The new campus, to be constructed in the city of Taicang, will mirror aspects of XJTLU’s existing provision and will open in 2020, with the aim of growing to accommodate 6,000 students by 2025.Launched in 2006, XJTLU is a joint venture between the University of Liverpool and Xi’an Jiaotong University, which has rapidly grown to a diverse international community of more than 12,000 students and 1,000 staff, who come from more than 50 different countries…

The partnership is based at the modern, purpose-built XJTLU campus in the city of Suzhou and its students gain both Chinese and UK degree accreditation. Many XJTLU students opt to finish their degree overseas, and there are currently around 3,000 studying at the University of Liverpool. A number of Liverpool students take the opportunity to spend a year of their studies in Suzhou.

According to the reported the proposed campus in Taicang is expected to contribute to the overall growth of XJTLU to 24,000 students by 2028. That is huge growth which, although it will not add greatly to the total number of TNE students, will certainly make XJTLU the world’s largest IBC.

Multi-dimensional TNE

Of course, there are many dimensions to TNE as I have noted here before and many universities are involved in some or all of the activities identified in the UUK report. The additional international aspects, not covered by the TNE definition but also important, include internationalisation at home, in terms of curricular elements, diverse student and staff bodies but also a general cultural internationalism too. These can be critical reinforcing aspects to an outward-facing TNE strategy. And, as noted before, all of these elements are a crucial counterweight to the parochial introspection and retrenchment promised by Brexit.

Insightful as always – looks to be a significant growth area also judging by the types of international partnership development roles we are seeing in the sector .