Released today, Universities UK International’s Gone international: Rising Aspirations report highlights the benefits of study, work and volunteer programmes for students, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The report comes at a pivotal time with continued uncertainty about the UK’s future involvement in Erasmus+. In stark contrast to the current domestic uncertainty, in Brussels and Strasbourg, the future Erasmus+ programme – to run from 2021 to 2027 – is already well underway to being moulded. At the end of March, the European Parliament voted overwhelmingly in favour to adopt the European Commission’s proposal for a renewed and invigorated Erasmus+ programme. The Commission’s proposal to double the budget was matched by MEPs who voted for a real-time tripling of the current budget to over €45 billion, 527 votes to 30. This was a no-brainer decision for them.

Because EU’re Worth It

Despite the price-tag, the Commission and Parliament’s enthusiasm for the programme is not without justification. In a recent survey by Eurobarometer, 27,424 individuals across the 28 European member states ranked Erasmus+, fourth as the most positive result of the European project behind only freedom of movement, peace and the Euro.

It’s not hard to see why. According to the recently published Erasmus+ impact study conducted by the European Commission, 80 per cent of participants found their first job in less than three months after graduation, and 40 per cent of participants who went on a traineeship were offered a job in the organisation they trained in. Erasmus+ graduates are more satisfied with their jobs and a higher share class them as ‘high income’ jobs compared to non-Erasmus+ participants. UUKi research found that UK students BAME students who study abroad are 17 per cent more likely to be in a graduate job six months after graduation and mature students who participate in these programmes earn 10 per cent more than their peers. Given the attainment disparity amongst BAME students highlighted in Universities UK’s recent #closingthegap report, mobility could play a crucial role in addressing this.

The UK economy needs Erasmus+

The UK currently lags in Erasmus+ participation and therefore in its access to these benefits. By the end of the 2018/2019 academic year, around 17,000 UK higher education students will have studied or worked abroad as part of the current scheme; compared to 44,000 students at French institutions.

What’s immediately worrying are the implications for the UK economy. Research by the CBI found that UK graduates fall short on key skills required for an increasingly globalised workforce. 7 out of 10 SMEs believed that future executives will need foreign language skills and almost half were dissatisfied with graduates’ language skills. 39% of employers were dissatisfied with graduates’ intercultural awareness.

It’s not just about jobs or academia. Studying or working abroad allows a unique engagement with different cultures, a chance to interact and form international networks and is the genesis of life-long friendships and relationships. A million children have been born to couples who met on Erasmus+.

Bringing the post-18 sector together

The programme doesn’t just offer opportunities to higher education students and staff. In 2014, it evolved from Erasmus to Erasmus+, offering mobility opportunities to different cohorts of learners, including those on vocational education and skills (VET) courses, primary and secondary school staff and youth groups, adult education students and sports organisations. Often participants from these sectors are from underrepresented groups and although mobilities may be shorter, they are as impactful.

A key finding from UUKi’s report on Widening Participation in Outward Student Mobility found that even short-term mobility was enough to increase skills, perceptions and open minds. For example, in the Erasmus+ VET programme coordinated at mainly at further education colleges, a typical student will undergo a 2-week Erasmus+ work placement in Europe as part of a foundation year or BTEC qualification. In many cases, these students will not have previously possessed passports.

Colleges are the main providers of VET courses and driving forces in social inclusion, but their funding has fallen in real terms since 2011-2012 according to a recent report by the Social Mobility Commission. They rely on the external funding provided through Erasmus+, which if removed, will be devastatingly discontinued. This would be counter-productive to the government’s intentions to rollout the new TVET qualifications as a vocational equivalent to A-levels in England and Wales. A compulsory requirement of the new TVET qualification is a 3-month work experience placement in industry, and Erasmus+ VET funding provides opportunities for students to undertake this abroad.

Let’s innovate, not duplicate

Despite the government’s own international education strategy published in March which set a target of doubling the number of outwardly mobile students by 2020, there’s no clarification on the future of the Erasmus+ programme.

Association to the next Erasmus+ programme would be a means of remaining internationally focussed after Brexit. It would help the government to meet its own targets, particularly in narrowing the attainment gap for BAME students and providing further education provision for underrepresented groups.

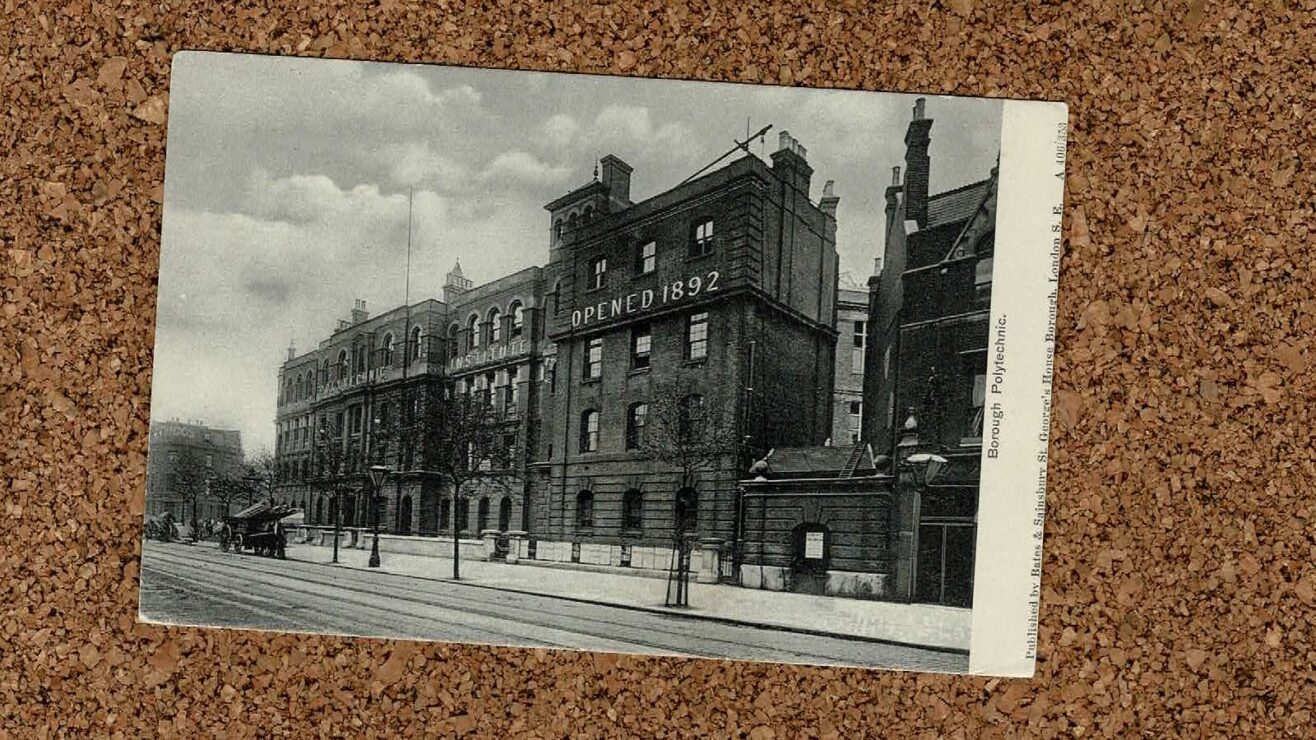

Beyond this, a dramatic cultural shift in the HE sector is needed; one where students actively choose their degrees based on international elements and mobility opportunities on offer. Universities now must stand in solidarity with organisations across the education sector to lobby for continued access to Erasmus+. A future programme, should at its core, be one about being a responsible international citizen. Given the Erasmus programme’s 30-year history, established acclaim and clearly demonstrable benefits, it’s difficult to envisage how a UK domestic replacement scheme would or even should emulate this.

80 per cent of participants found their first job in less than three months after graduation: isn’t this the same with all graduates? 40 per cent of participants who went on a traineeship were offered a job in the organisation they trained in: isn’t this the same with all graduates? UK BAME students who study abroad are 17 per cent more likely to be in a graduate job six months after graduation: isn’t this the same whether via Erasmus or via their uni’s own arrangements? Erasmus+ graduates are more satisfied with their jobs and a higher share class them as… Read more »