Universities were hard to find at a Conservative Party Conference whose fringe seemed to be much more exercised by culture war wedge issues than economic concerns.

It underlines a particular problem for the “solution to growth” lobbying position that the sector tends to adopt – the HEPI “Vice Chancellors Manifestos” event was largely attended by sector people talking to themselves, while the sessions on free speech and family values were standing room only.

But while universities and home domiciled students struggling with a cost of living crisis were hard to come by, international students popped up in all sorts of places.

Pretty much every event on immigration (and they were plentiful) contained references to the numbers of study visas being issued since the post-Brexit liberalisation of the system.

The headline concern was usually about net migration – and with evidence in short supply on whether the new burst of students are likely to stay or go after study, ministers were generally able to point to the forthcoming PGT dependent ban as action to tackle what are for now perceived “abuses” in the system.

But listen closely and what was also emerging was concern not just about international students as potential contributors to net migration, but contributors to pressure on infrastructure while they’re here – especially housing.

House music

At HEPI’s manifestos event, some “notable areas of consensus” included the “growing shortage” of student accommodation. University of Birmingham VC Adam Tickell argued that universities need to ensure that we don’t let international students “crowd out” students from within the UK:

This is non-trivial; students need places to live and study in and, as the financial settlement currently depends on a cross subsidy from international students, we will need to ensure that there is enough accommodation and that our estates allow us to teach at high quality.

And University of Sussex VC Sasha Roseneil called for incentives for local authorities and universities to work in partnership to develop public student housing:

Together they should have access to the Public Works Loan Board to build accommodation and the community facilities needed to support increased numbers of students in particular neighbourhoods. This would give universities access to cheaper capital and local authorities would get a much needed revenue stream from student rents, and a greater say over the type of accommodation built.

This is a version of the debate that takes rapid international student growth as its natural start point, and calls for more housing. But elsewhere on the fringe, the concern was on dampening demand rather than increasing supply.

Immigration minister Robert Jenrick argued that net migration needs to come down:

…because it’s having real world implications in communities right across the country to the point where students are struggling to get the housing that they want in the university towns or cities that they want to study in them.

Madeleine Sumption, Director of the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, reminded the Policy Exchange audience that even if a minority stay, a minority percentage of a growing number is still large:

Although I would still expect a majority leaving, even if you have only of 10 to 20 per cent of international students remaining permanently in the UK, when the number of students is so high, that’s still actually a non-trivial contribution to net migration.

But as well as the “leaver” figure getting closer to the “arriver” figure, what’s clear around the fringe is that the numbers while here were a concern too. Jenrick:

Although they may be transient and some may leave the country, nonetheless it’s placing unbearable pressure on our housing right now. And that’s one of the many strong arguments for taking a stronger approach than we have in the recent past.

And the taxpayer’s alliance reflected that view:

So at the moment we have a system where effectively the only check on student migration is how fast can universities expand their courses. And this migration still matters. Universities catch the benefit of this migration, but all the externalities are placed on the big cities with public services and housing pressures.

This was all mixed in with some Matthew Goodwin stuff on national identity. But separate that stuff from sheer pressure on rental markets, and this becomes a problem for a sector that is used to arguing that international students have a negligible impact on long term migration to the UK.

How big a problem that is is harder to quantify.

Extrapolations

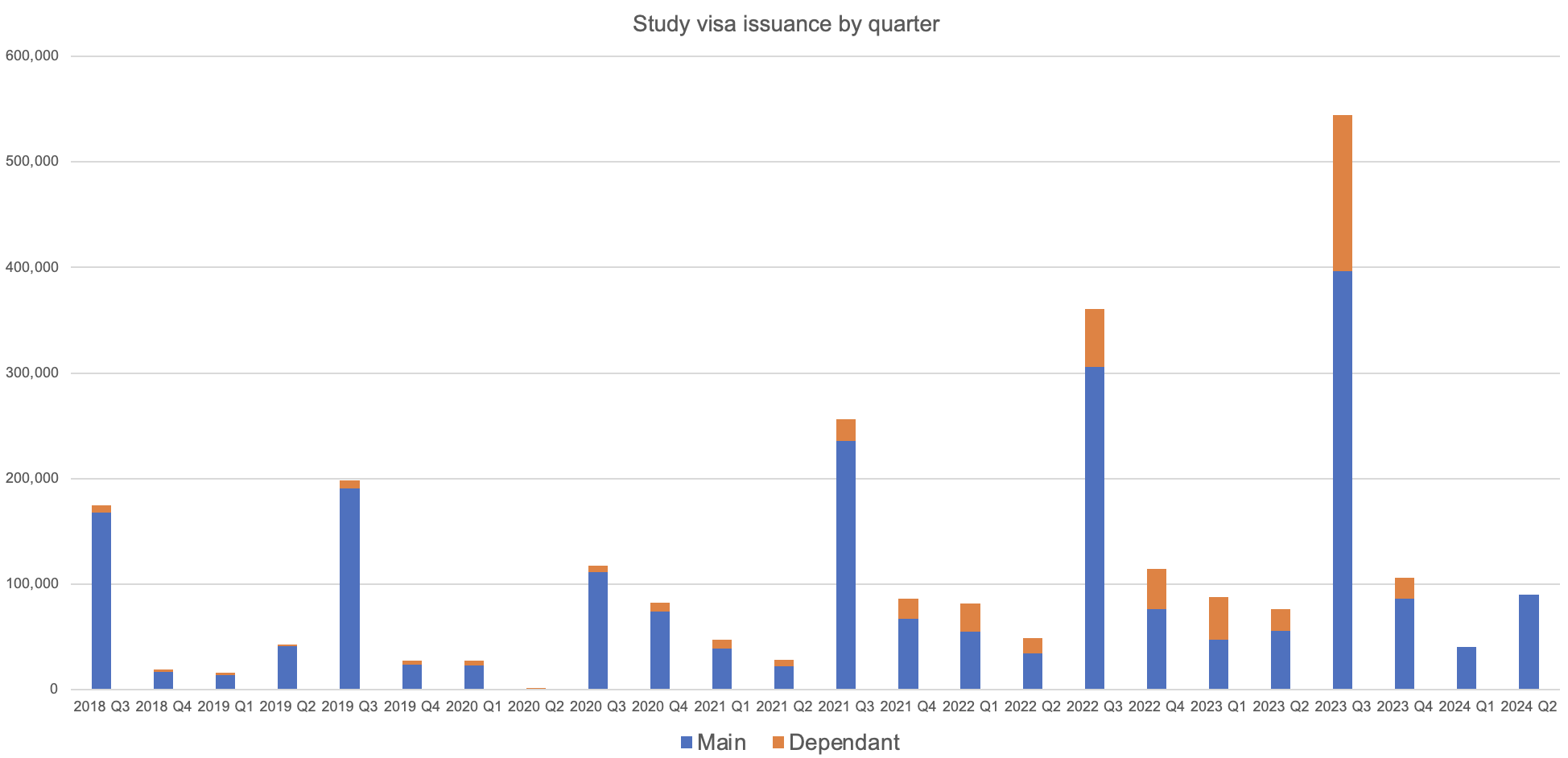

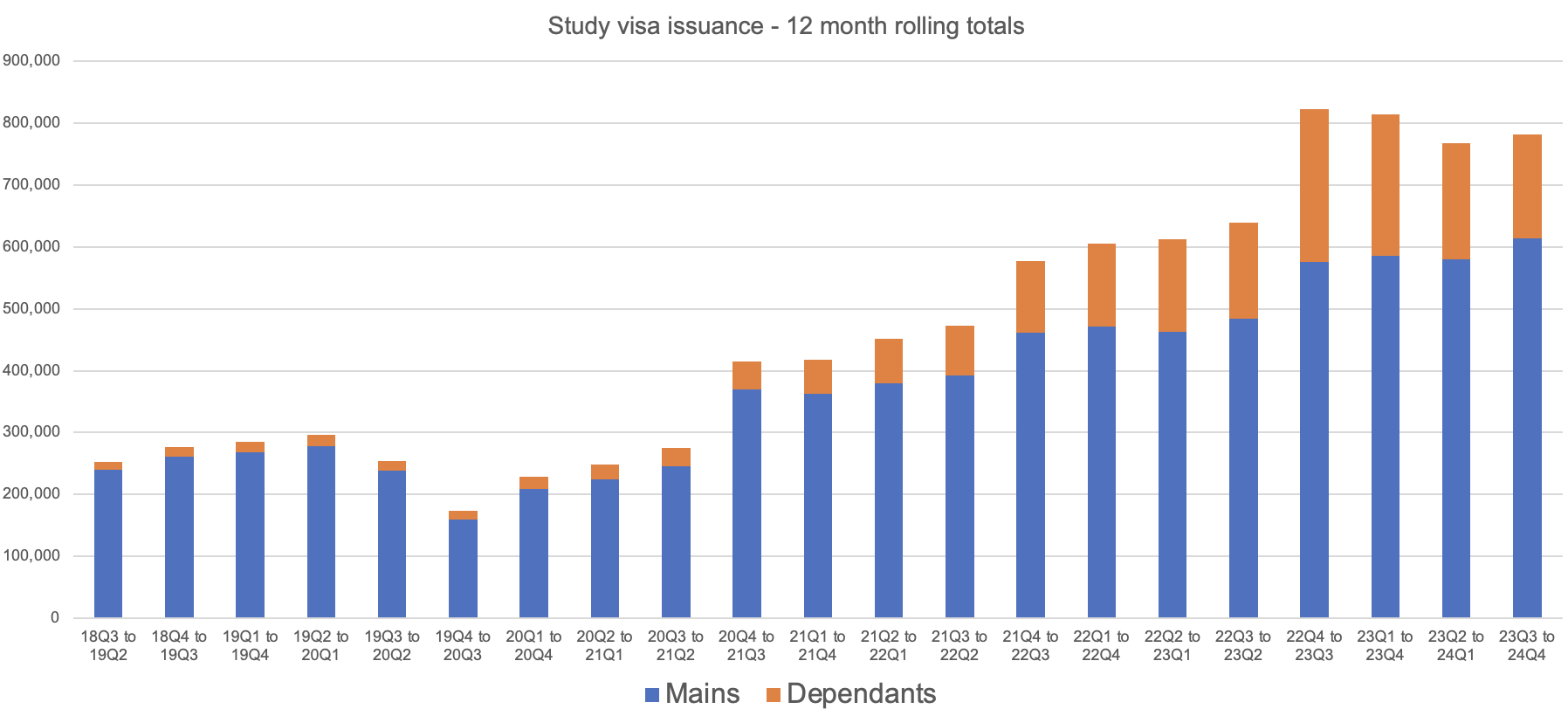

Predicting the future is notoriously difficult, but I’ve had a stab. Here I’ve applied the increases that we’ve seen to study visa issuance over the past twelve months and I’ve run that increase on again to the next four quarters:

Given the ban for programmes starting on January 1st, dependant numbers are obviously about to all but disappear – but there’s plenty of providers introducing November intakes to get around that ban, so I’ve added 10k to the expected increase for 2023 Q3. Here’s a version that’s then smoothed with 12 month rolling totals:

We don’t yet know the impact that the ban has had or will have – demand may be down, steady or up, and there’s evidence of different impacts on different providers, which will partly be about each provider’s country mix given the ban will be more strongly felt in Nigeria than India.

It’s worth noting that in England alone, OfS’ analysis of financial sustainability shows a sector intending to grow its non-EU student numbers to grow by 35.3 per cent in the next two years. That’s a rate of increase that’s not far off those charts above at all. And even if the treasury was to make PBSA investment an easier thing for universities, that will do nothing for the period of expansion the sector intends.

Put another way, growth is the plan. Without a plan, that is, to house the growth. It’s therefore unsurprising that Universities UK’s big new strategy doesn’t mention accommodtion at all.

If demand does continue to grow, the startling thing is that that growth may well cancel out any impact of the dependant ban. In other words, even if dependents are not in the mix and there’s no impact at all on net migration, (and that would be to ignore take up of the graduate route – a key driver of recruitment and an additional pressure given graduates tend to need to live somewhere) numbers are growing so fast that the pressure they place on housing infrastructure will continue to grow.

A crisis is brewing

Getting a clear sense of those pressures is hard given the landlord lobby and letting agent industry’s tendencies to distort any shred of evidence in their interest. But arch capitalism tends to know the score.

Cushman and Wakefield’s annual student accommodation report is pretty clear that there’s a brewing “student accommodation crisis” across the UK. It says average private sector rents in halls outside of London now sit at 77 per cent of the maximum available maintenance loan, equating to £7,632.55 per year – despite large portions of students not receiving anywhere close to that amount to cover living costs.

On the whole rents in Purpose Built Student Accommodation (PBSA) have risen by more than 8 per cent this year, compared to 2022-23 (£7055.71 in 2022 to £7,632.55).

It says that fewer than one in ten places are now affordable for the average student, with cities including Durham, Birmingham, and Exeter being highlighted as offering even less affordable housing options priced below the average maintenance loan.

And this is about both demand, and supply failing to catch up – the net increase in beds for the 2023/24 academic year is just 8,760 – with the national average student-to-bed ratio standing at 2.1:1, emphasising a desperate need for additional accommodation units.

The impacts on students are huge, and visceral. Ask any SU advice centre and you’ll know that this BBC News story is almost certainly not an isolated incident – and a reputational disaster in the waiting:

When Nazmush Shahadat arrived in London from Bangladesh he had nowhere to stay. He had been accepted on to a course to study law, but found university accommodation too expensive and he couldn’t find a house to live in.

Mr Shahadat said things “turned dark really soon”, and he ended up sharing a two-bedroom flat with 20 other men. “I never expected to live in a place like that – I still have my scars,” he said.

With multiple bunk beds crammed into a room and shift workers coming and going, he said it was impossible to sleep and he was often bitten by bed bugs.

In the quotes accompanying the story, DfE points at universities. UUK points at students needing to establish living arrangements before arriving. If students were asked, they’d blame a system that allows this to happen. But the grim circularity of that blame game doesn’t solve the problem.

Reasonable expectations

If, as I do, you think that students who are recruited to study here from another country should have the right to somewhere to live that’s of a reasonable price, a reasonable quality and a reasonable distance from campus, the evidence is growing that large numbers of students are not able to access that basic right.

There’s a real danger that there’s complacency over the impact of the dependant ban both on migration levels and getting the government off the sector’s back. And there’s scant evidence that Purpose Built Student Accommodation projects are being green-lit to keep up with the increases – with plenty of evidence that overall supply is going in the opposite direction.

The sector will sometimes postulate that the reason it has grown so much is to prop up the unit of resource. But even if the government doubled the home domiciled unit of resource tomorrow, history tells us that once the demand is being met, universities will continue to take the money. The question is whether they should – or will be allowed to – if there’s nowhere for those students to live, with knock on impacts for home domiciled students and local communities.

So whether you think the future should be about growing supply or dampening demand, the bottom line is there’s not enough student housing – and I’m no so sure that prioritising sector income to maintain or improve the student experience is worth it if enrolled students (both home and international domiciled) aren’t able to make use of that provision because of their resultant distance from campus.

Solving the problem, or at least avoiding it getting worse, could fall to different actors.

- You could blame – and place the responsibility for the future on – students themselves. But students have dreams, agents lie, providers omit to reveal how hard the housing market is getting, and there’s nothing approaching decent information that would allow even a savvy student to avoid stumbling into a shortage area.

- You could – as the government does – blame and place the responsibility for the future on local authorities. But their powers are limited, and they show no signs of wanting to be an active player in this part of the wider housing crisis.

- You could blame – and place the responsibility for the future on – universities. I continue to argue that providers that recruit a student to live away from home should have a sense that that student can access housing. But it’s hard to do, the incentives point in opposite directions, and despite nudges from Universities UK earlier this year, vanishingly few are collaborating with each other and their local authority in the way we’re starting to see in places like Nottingham.

- You could blame – and place the responsibility for the future on – PBSA investors. Helping universities access terms to at least co-invest would help. But capitalism is going to capitalism – and there’s few signs while interest rates remain high that investors of any stripe will be keen to invest in the sort of low-cost provision that we know emerging markets need.

And so if none of the above is going to work, we’re back to the Home Office and UKVI. And as such, here’s what I don’t understand.

CAS-tration

It’s easy to think of the increases we’ve seen in recent years as one of letting market forces rip – but this is a regulated environment. Over the past few years, as we’ve been seeing angles on the graph the likes of which have never been seen before, UKVI has been issuing allocations of Confirmation of Acceptance for Studies (CAS).

Every year, providers have been able to apply for an increase in their CAS allocation of up to 50 per cent of their previous year’s CAS allocation. From an educational infrastructure point of view – staff, space and so on – any request increasing the student body by 20 per cent or more “may” trigger an “Educational Oversight inspection” by the relevant educational oversight body.

The”body” is SFC/QAA in Scotland, HEFCW/QAA in Wales, and the Office for Students in England. Whatever else they do on quality, none of the material they may or may not have supplied is much use when judging contemporary or future educational infrastructure. And there’s certainly no evidence of any bespoke “inspections” to this end, at least not on universities.

For its own part, UKVI says it looks at all sorts of things when it gets an increase request – including agents, the student-teacher ratio in classes for the courses provided, and the total student capacity of the premises and any capacity restriction written into planning permission.

This is not evidence, if ever asked for, that the rest of us can access.

But either way, what the assessment as described doesn’t do is look at local infrastructure – evidence, for example, that students recruited will be able to access somewhere to live that’s of a reasonable price, a reasonable quality and a reasonable distance from campus. Or get on the bus. Or get a Dentist. And so on.

So for me it’s pretty simple really. If the mix of actors that aren’t UKVI aren’t able to act alone or in partnership to influence supply to ensure students have somewhere to live, the Home Office should change UKVI’s rules so that universities are required to demonstrate capacity both in the provider and in the area – and reduce demand if they can’t.

Put another way – a number of the universities that have introduced November intakes to get around the Jan 1st dependant ban also appear to be in acute shortage areas on Cushman and Wakefield’s watch list. They should be asked where those students are going to be staying on Christmas Day.

One size doesn’t fit all, several HEIs have plenty of on-site accommodation still available which they’d be very happy to fill

I’m sure that’s true – although I am increasingly coming across providers where there’s empty accommodation because it’s too expensive for the international students being recruited

Some examples of such students though don’t consider what’s included in the rent (eg utilities, security), don’t add in transport costs and settle for accommodation of a very low standard, so there’s definitely room for a better sales pitch. Some are paying more overall without realising it by living off campus. But the main point is that there is no universal crisis, though there is locally in places.

While there may not be ‘a universal crisis’ there are certainly ones ‘locally in places’ – and in far too many places, as well as in a growing number of such places. The agents Jim cites will never co-ordinate a solution, and definitely not any time soon. So his proposed UKVI strategy is spot-on! Us are businesses and they will put the raking in of ever more fees from international students above considerations of ensuring a decent ‘student experience’ for them (and also for their home students caught up in the ‘local’ accommodation crisis) – hence it needs intervention by… Read more »