These are uneasy times for UK research funding.

For the optimists among us, a pot of gold lies at the end of a 2.4%-of-GDP-shaped rainbow, promising unprecedented levels of public and private investment. Chris Skidmore, the minister for universities and science, is now cheerleader-in-chief for this camp, having made a series of thoughtful speeches over recent weeks on “the road to 2.4%”.

Those of an Eeyore-like disposition point instead to clouds on the near horizon: the economic chaos of a no-deal Brexit, delays to the next spending review, and Augar’s fee cuts limiting the scope for internal cross-subsidy of research.

Delivery plans

The release this month by UKRI of a series of delivery plans sheds light on what to expect over the next eighteen months, but it’s hardly surprising that these haven’t yet been buttressed by the longer-term strategy that was originally expected by summer 2019.

As uncertainty swirls through the sector, stable flows of funding are more prized than ever. So the future of the annual £2 billion of quality-related (QR) funding, allocated to universities on the basis of their performance in the Research Excellence Framework (REF), is again under the spotlight.

New analysis by the Russell Group suggests that QR has seen a real-terms fall of 13 per cent in its value over the past seven years. And last week, several witnesses appearing in front of the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee highlighted pressures on QR budgets as a growing vulnerability in the research system. In his evidence to the same committee, Chris Skidmore said that he was “fully aware of the historic reduction in real terms in QR funding” and that he hopes to announce a “significant uplift” once the spending review is completed.

Pump up the volume

This dialling up of the political volume on QR comes at a time when preparations for the next REF are moving up a gear. As the term-time pressures of teaching and exams recede, many universities will be embarking on their annual REF stocktake, with under 18 months left on the clock before submissions to the 2021 exercise. This in turn is likely to trigger fresh bouts of concern over the managerial, personal and workload demands of the REF, and its role in institutional and research cultures.

Too often, debates about the REF end up being dominated by those who shout loudest. And these two strands of discussion – one around the scale, value, and benefits of the QR funding derived through the REF; the other around the design, purposes, costs and burdens of the REF as it’s implemented – become decoupled. There has also been little systematic effort to look beyond the headlines, to understand changing perceptions and experiences of the REF among researchers at different career stages, and in diverse institutions.

So over the past year, a team from Cardiff and Sheffield universities have been working with Research England to pilot an experimental, more distributed approach to evaluating the exercise: the Real-Time REF Review.

Tick tock

Our findings, published today in summary by Research England and a longer working paper, are based on the survey responses of almost 600 researchers – spread across four universities and eight disciplinary units of assessment – and in-depth interviews with a much smaller group of REF coordinators and managers.

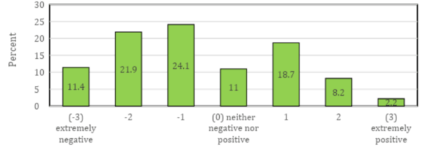

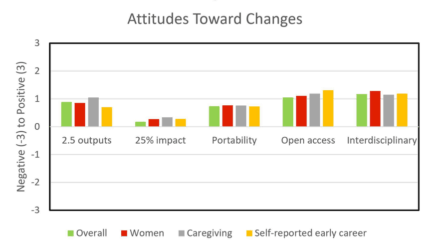

The results may surprise some people. Overall, opinions are mixed towards the REF. The majority of views were moderately negative, but perhaps less strident than is sometimes assumed, with a more positive reaction to the reforms that followed the 2016 Stern Review.

REF 2021 was viewed as more flexible and supportive than its 2014 predecessor, in part because of its heightened focus on quality over quantity of outputs. The incentives it provides for external engagement and impact were also seen as helpful. And support for open access and open research was regarded overall as the most positive change in REF 2021.

Concerns about the REF focused on its potentially detrimental impacts on academic autonomy, authenticity, morale and wellbeing – and on its potential to encourage game-playing by institutions.

Just under one-sixth of respondents reported their departments using potentially pressurising tactics linked to the REF, such as expectations of a role change. Fifteen per cent of respondents reported that they were asked to change the focus of their research to accommodate the REF. While this is a relatively low number, it raises questions which merit further analysis. The fact that interviewed managers did not feel able to comment on such influences suggests a degree of divergence between the strategic aspirations of the REF, and the realities on the ground for researchers.

Times they are a changin’

As the current REF cycle runs its course, it will be important to understand how experiences and attitudes towards the exercise are changing. This pilot represents a first step, but a larger longitudinal study would provide a richer picture of the effects of the rule changes to REF 2021, and the implications of these for researchers’ work and wellbeing.

These and other systematic approaches to research on research are vital if we want research policies and funding to be informed by rigorous evaluation and evidence. Even with QR funding under pressure, the REF remains the single most important method of funding UK research. We need robust evidence to inform future cycles, to ensure that REF delivers maximum – if diverse – benefits to universities, government and wider society, while minimising any negative effects on the health of our research system and those who work in it.

The Real-Time REF Review pilot study is available in summary here, and as a longer working paper here.