The sheer scale and diversity of international talent who choose to pursue a degree from a UK university is a testament to the sector’s global reputation and a boon to campuses across the country – students from over 190 countries and territories were granted visas to come and study in the UK in 2023.

Some countries are larger sources of international students than others, with more populous countries generally tending to send more. Throughout the 2010s China was by far the largest source of international students in the UK, but a few years into the 2020s that picture has changed dramatically. Through working together, government policy and university strategy aligned and steady progress was made towards the aim of diversifying international student recruitment, with India and Nigeria emerging as the main alternative sources of students. However, recent moves by the government to reduce net migration by reducing international student numbers have halted the diversification momentum, with current trends pointing back towards increasing dependence on Chinese students.

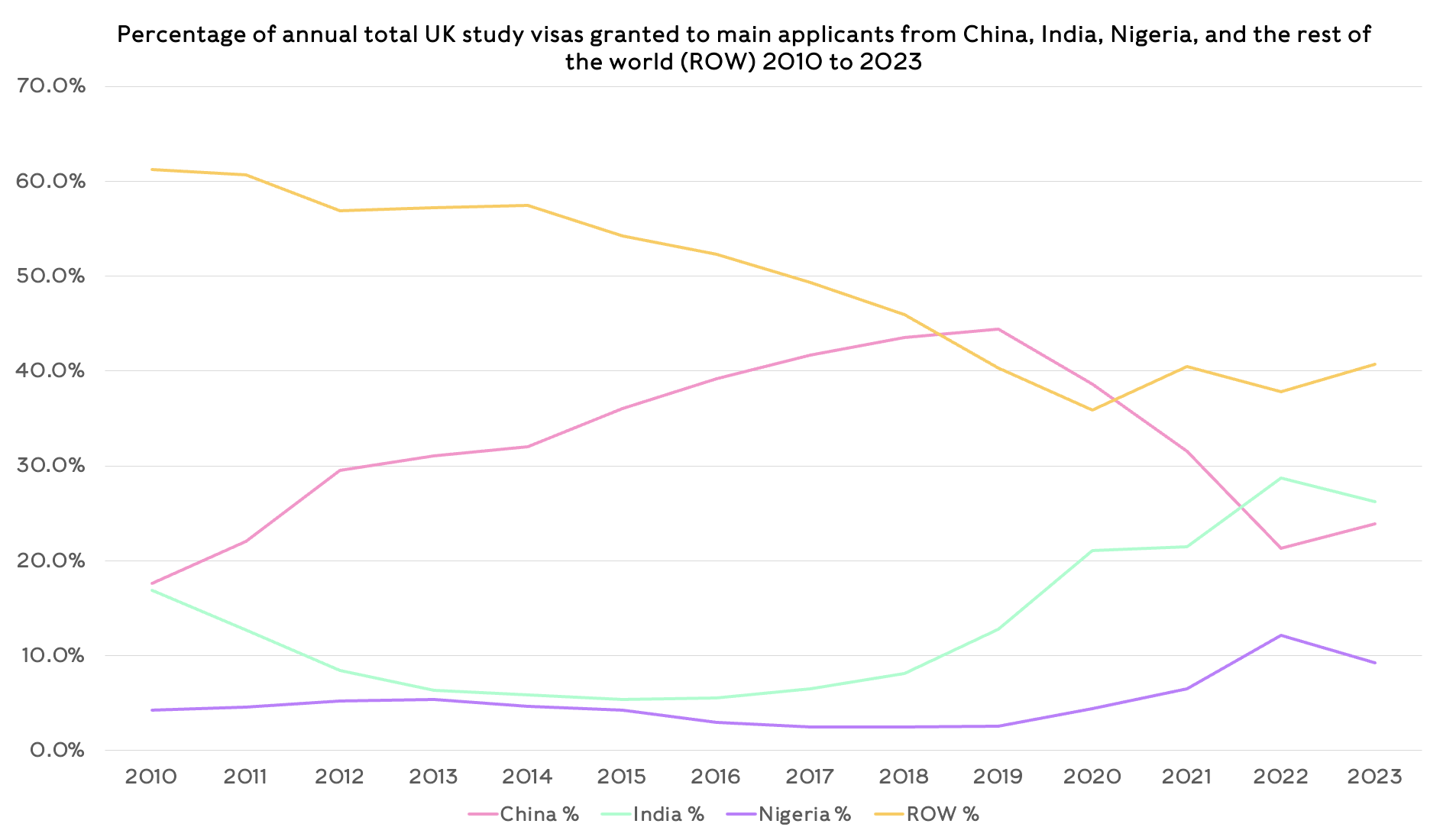

The increasing overall size of the international student population in the UK over previous decades, coupled with the rising significance of international student tuition fee income as a factor in the financial sustainability of the sector, have led to greater scrutiny on the specific makeup of the international student body. Every year from 2010 to 2021, Chinese nationals accounted for the highest number of UK study visas granted. Just over a third (33.7 per cent) of all study visas granted to main applicants from 2010 to 2021 were to Chinese applicants.

China’s market share of main applicant study visas granted in a year peaked in 2019 at 44.4 per cent. The volume of Chinese students coming to the UK to study, and the proportion of the international student body they made up, gave rise to concern and commentary regarding “over-reliance” on tuition fee income from students from a single country, and “over-exposure” to any geopolitical shocks which might lead to sudden drops in the flow of students from China to the UK.

Responding to these concerns, the government’s 2019 International Education Strategy set out the target of 600,000 international students studying in the UK each year by 2030 and highlighted priority countries with “significant potential for growth” including India and Nigeria. Spurred on by the ambitions of the strategy, and facilitated by the opening of the Graduate Route visa in July 2021, universities have made a concerted effort to diversify and ensure the long term sustainability of their recruitment of international students.

This was not an effort to reduce the intake of students from China, but rather a focus on boosting recruitment from other key countries. Students from China are, of course, equally welcomed and valued by universities as their counterparts from India, Nigeria, and elsewhere. Convening a diverse student body is, on its own merits, sound practice for a university.

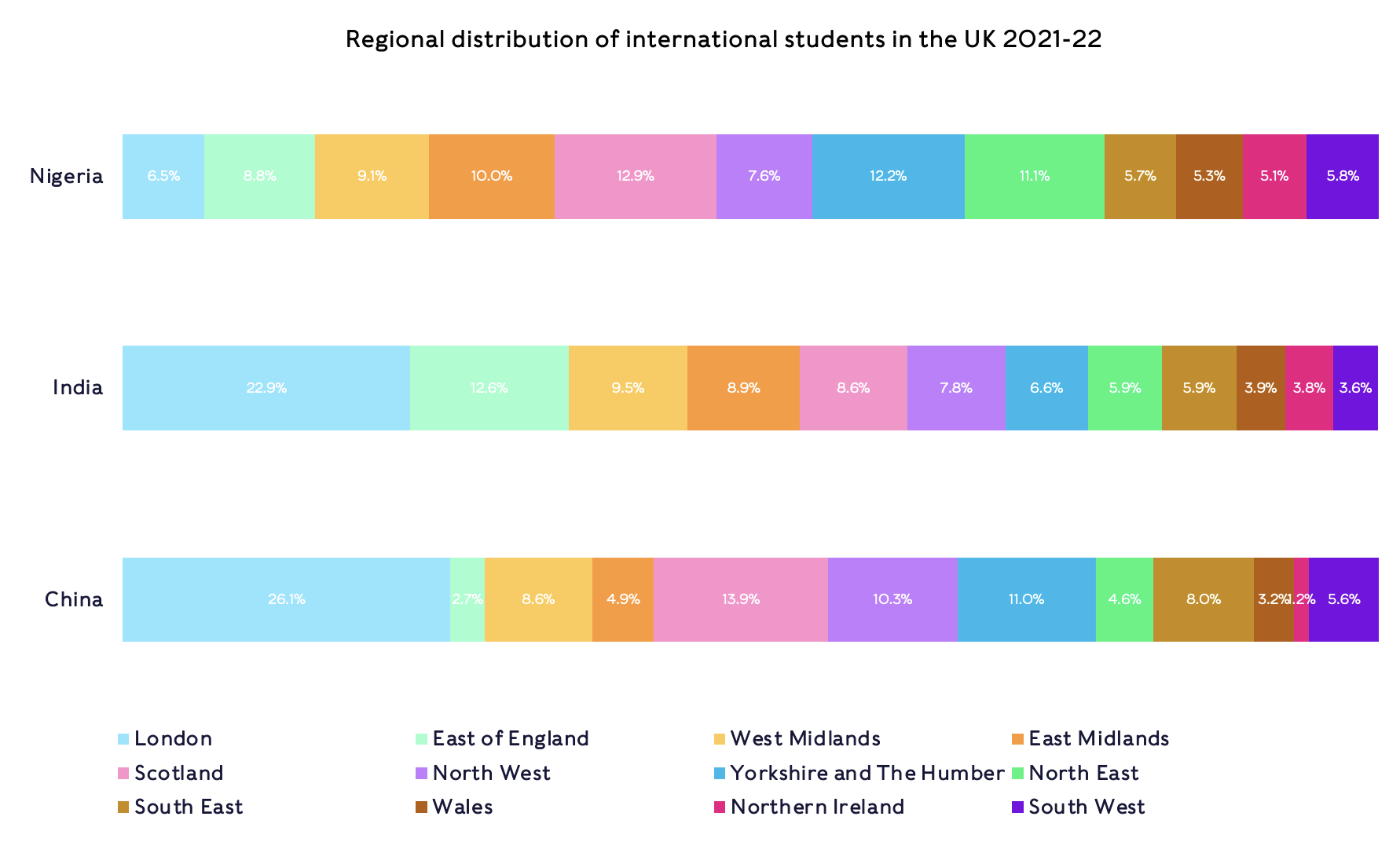

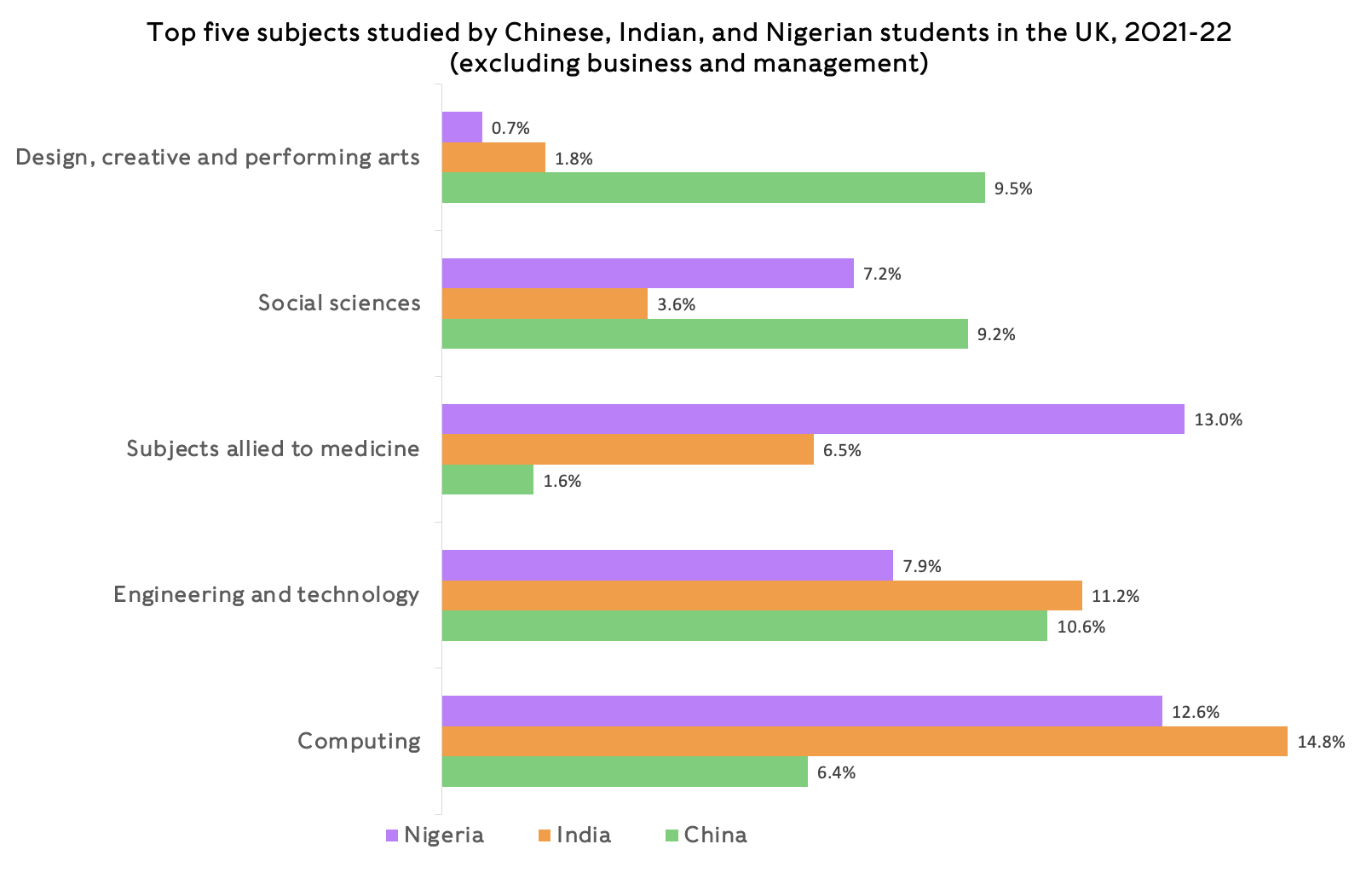

At the national level, international students are not a monolith and students from different backgrounds bring benefits to different parts of the UK and the sector. Over a quarter (26.1 per cent) of all Chinese students in the UK in 2021-22 studied at London based universities, compared to only 6.5 per cent of Nigerian students who are relatively more heavily concentrated in Yorkshire and the North East. Nigerian students are more heavily concentrated in subjects allied to medicine, Indian students are particularly well represented on computing courses, while arts and design subjects are a popular choice for Chinese students.

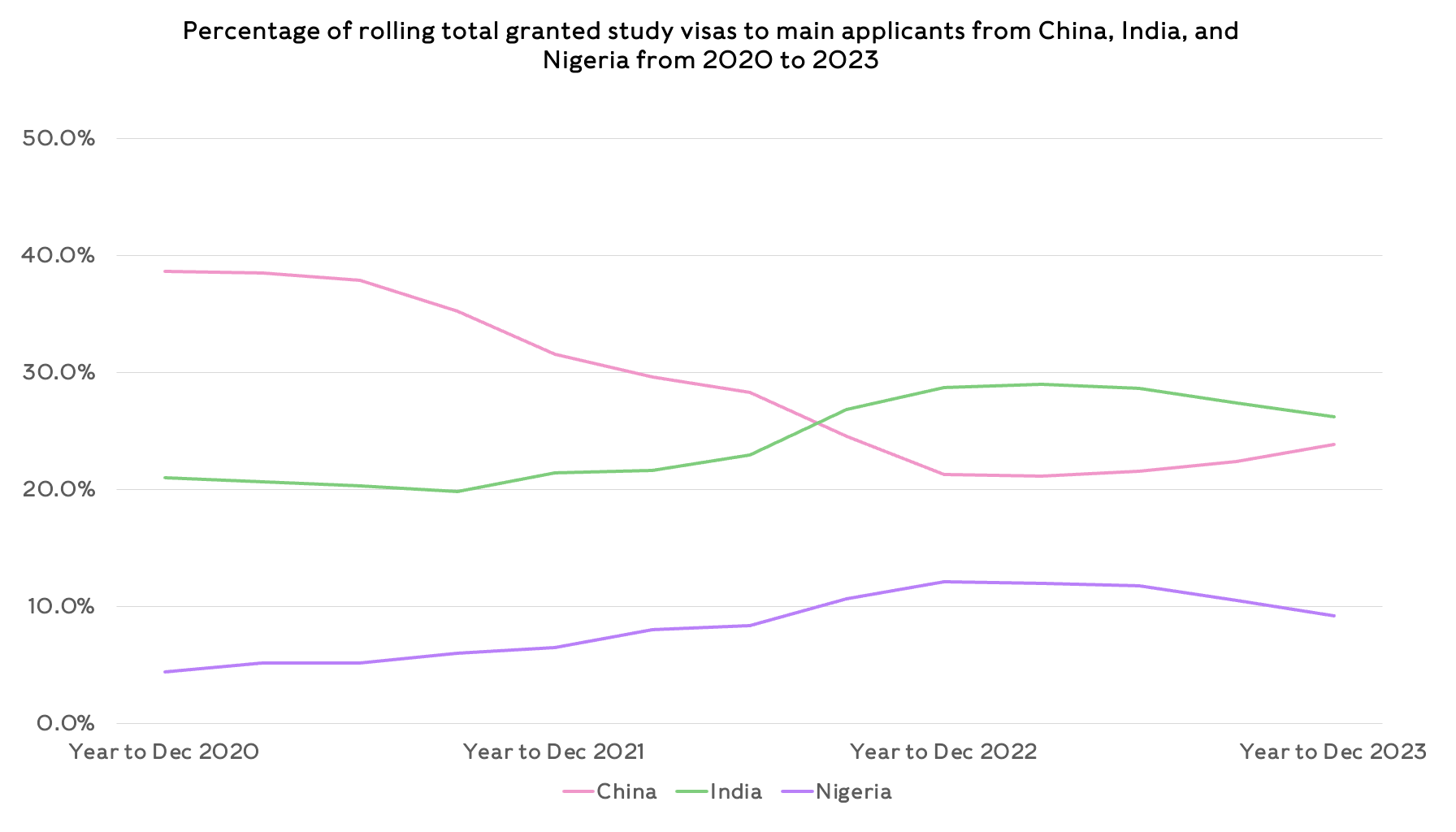

Study visa data published by the Home Office demonstrates the impact of diversification. The share of study visas granted to main applicants from China fell from 38.6 per cent in 2020 to 31.6 per cent in 2021 and fell further to 21.3 per cent in 2022. India’s share grew from 21.1 per cent in 2020 to 28.7 per cent in 2022, overtaking China for the first time in over a decade. The share of study visas going to Nigerian students also increased over this period, from 4.4 per cent in 2020 to 12.1 per cent in 2022.

Quarterly analysis shows that between 2020 and 2023, the peaks for market share of study visas granted achieved by India came in the Year to March 2023 (29.0 per cent), and by Nigeria in the Year to December 2022 (12.1 per cent). India and Nigeria led the way in growth but other markets also made more modest contributions to this trend – between 2020 and 2022, Pakistan’s market share grew from 2.8 per cent to 5.8 per cent, Sri Lanka’s from 0.3 per cent to 1.2 per cent, and EEA nationals newly requiring visas post-Brexit accounted for 4.7 per cent in 2022.

However, alignment between political stakeholders and the sector that facilitated this achievement has eroded over the last year and a half. Recent negative media and political rhetoric around international student numbers, connected to wider debates around net migration levels, and subsequent actions by the government – including the removal of the right for PGT students to bring dependants to the UK and the announcement of a review of the Graduate Route by the Migration Advisory Committee – have contributed to a reversal in the diversification trends outlined above.

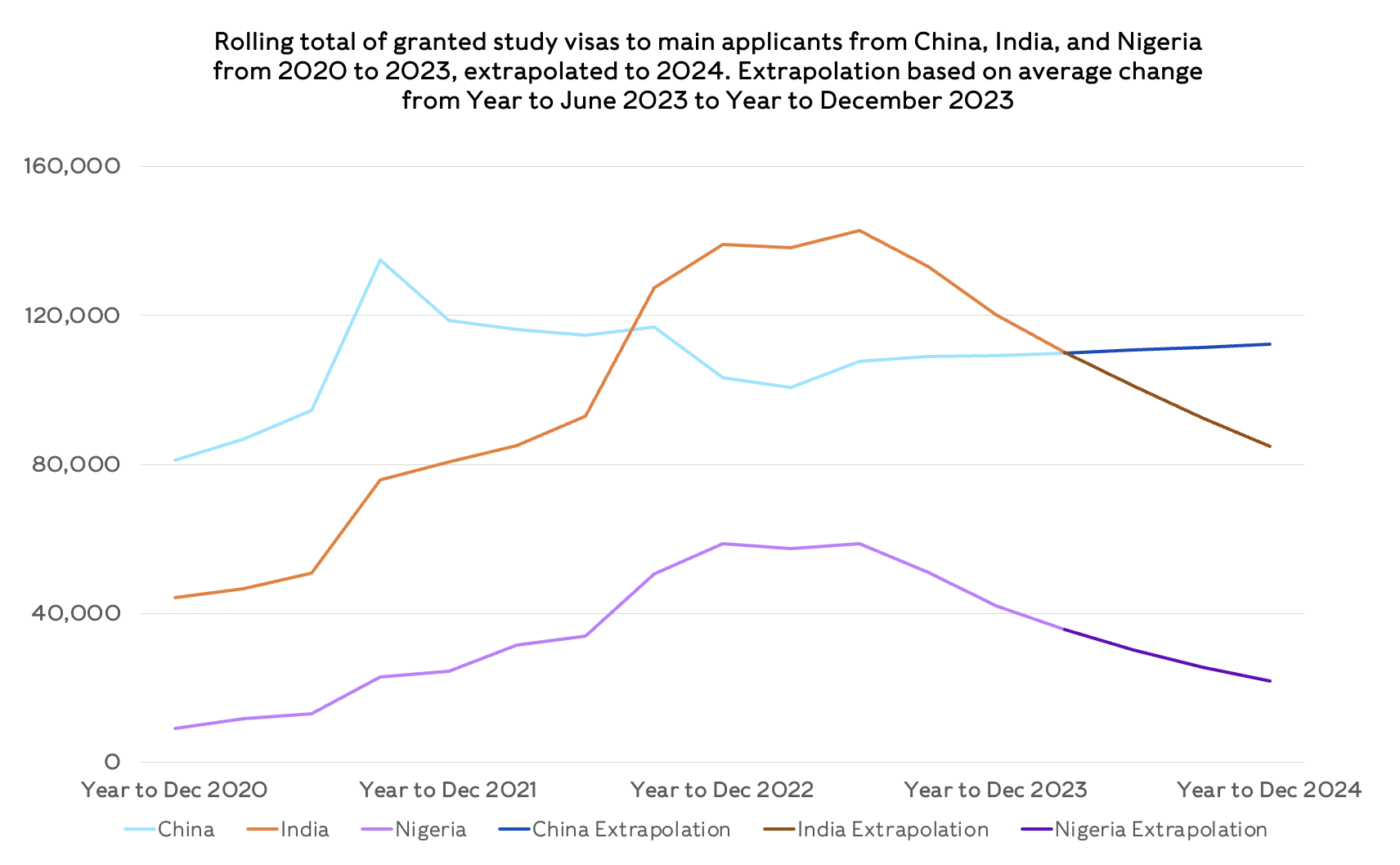

Early signs visible in the visa data published by the Home Office indicate the number of visas granted to Indian and Nigerian students were rising up to the Year to December 2022, but have since plateaued and begun to fall. In the Year to December 2023, visas granted to Chinese students were at their highest point since the Year to September 2022, while visas granted to Indian and Nigerian students were at their lowest point since the Year to June 2022. A direct comparison shows that 43 per cent fewer study visas were granted to Indian nationals, and 63 per cent fewer to Nigerian nationals in Q4 of 2023 compared to Q4 2022.

Looking forward, this slide looks set to continue with UUK analysis showing an ongoing contraction in international student enrolments through 2023 and into 2024 – trends we expect to be reflected in forthcoming Home Office visa data releases. Using data from post the May 2023 announcement of forthcoming rules changes to limit PGT students from bringing dependents to the UK, we can extrapolate forward what a continuation of these trends might look like through 2024.

If the trend from July 2023 through to December 2023 were to continue through 2024, we might expect to see visa issuances to Chinese students up by 2.8 per cent in the year to December 2024 compared to the year to December 2023. Of significant concern is that if these trends continue, student visas granted to Indian students are set to fall by 29.3 per cent, and student visas granted to Nigerian students would fall by 48.3 per cent. Such a dramatic drop off in Nigerian and Indian student numbers would represent a significant backslide in the sector’s efforts to ensure international recruitment is sustainable in the long term.

The progress made on diversification up to 2022 did not represent mission accomplished for the sector. Shifting reliance from a single market to three markets is an improvement but, as has been demonstrated since, does not provide sufficient insulation against external shocks and geopolitical headwinds. Recent interventions by the Deputy Prime Minister further demonstrate the need for a joined up approach across government – when the sector and the government are working in tandem, supported by a stable policy environment, we can deliver fantastic outcomes for the country on exports, soft power, sustainability, and quality.

If we can come through this period with the Graduate Route unscathed, opportunities exist to further develop recruitment pathways in the other IES priority countries, capitalise on TNE pathways from South-East Asia, and tap in to pent up European student demand. On the other hand, a return to the constrained visa environment of the 2010s, with an uncompetitive post-study work offer, risks alienating prospective international students from India, Nigeria, and beyond, leaving our universities in a precarious, over-exposed position.

We have to hope that the government can fill the shortfall in money when/if the numbers fall to the point Universities have to start reducing staff as the international students are the single source of income that exceeds operating costs, even Russell Group Universities such as mine cannot survive on UK tuition and research funding alone. As to Chinese student numbers, yes they’ll fall off as China see less and less return on the investment as our I.P. security improves. The Recent naming of the Chair of the HECEA (Higher Education Chinese Employees Association) in the press, and her suspected… Read more »

Hi, I tried to find an article about the HECEA thing but couldn’t, do you think you could provide and article title or link? Cheers!