Back in 2012, not long after moving from Oklahoma to Massachusetts, a man called KC Green was working during the day while trying to kickstart his comics and graphic design career.

To cope, he began taking medication to combat depression – it at least got him through the week.

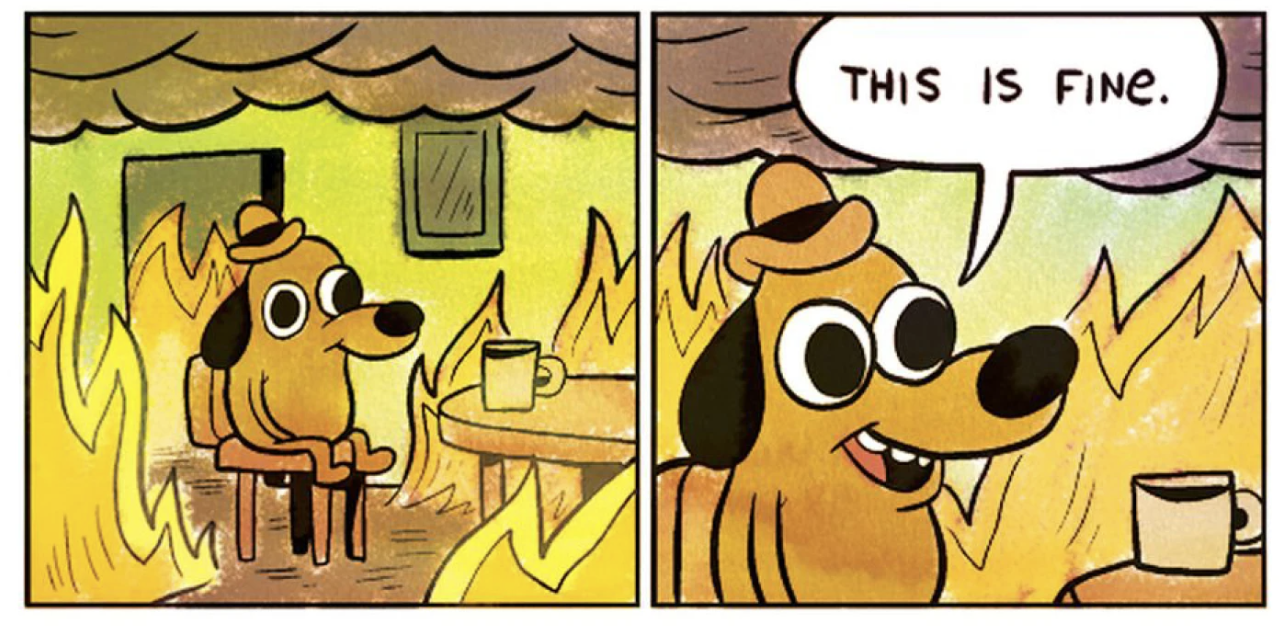

In that period, he came up with an idea which has become the ultimate viral meme:

It’s a very simple feeling that we all have, of things going bad around us and ignoring that feeling because there’s not much you can do about a house on fire. So a house is on fire and a dog who’s kind of the first comic character in the comic “Gunshow” I did.

He’s sitting there completely happy, very wide eyes, and just says, This is fine, when everything is burning around him. Like, literally everything is just on fire.

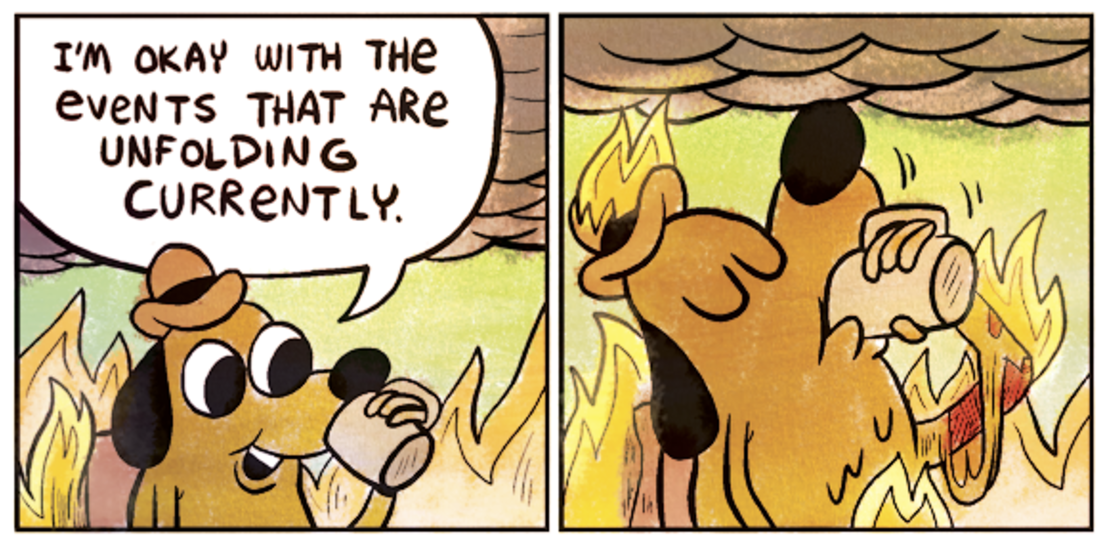

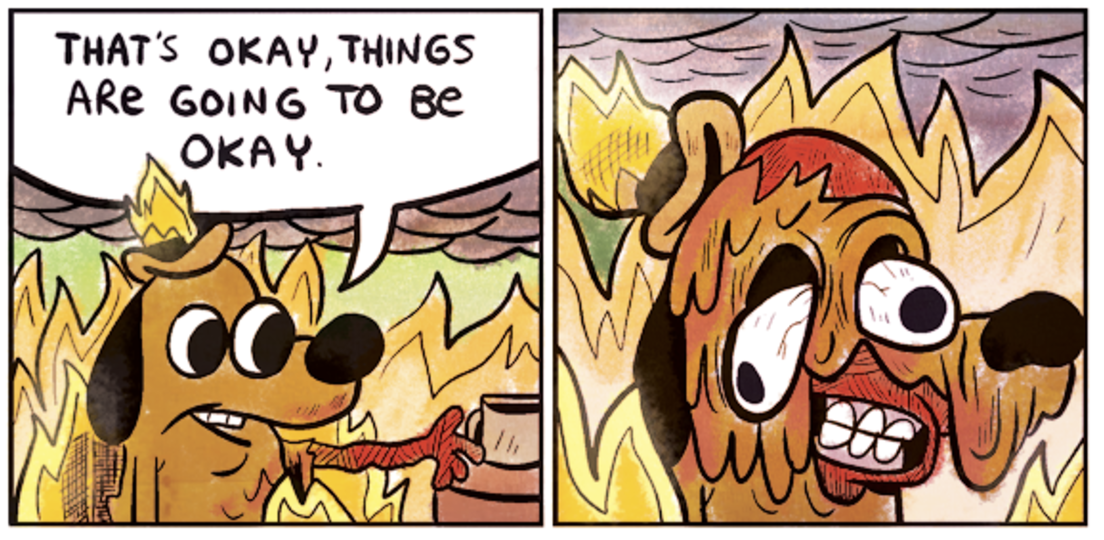

He continues to say, Uh, I’m okay with the events that are currently unfolding. Then his arm catches fire and he [says], That’s okay. Things are going to be okay. And then he melts away.

A flawed framework

There’s a strong argument to say that the way in which the Office for Students (OfS) evaluates the finances of its regulated providers is flawed.

I’m not talking about lagged indicators or its access to data – although that does seem to be an obvious problem given the “first slowly, then all at once” nature of these things.

Its definition of viability is based on a calculation of material risk of insolvency within three years – via a look at liquidity. Sustainability is more of a judgement about the ability to deliver on contractual and regulatory requirements. Take them together, and the argument goes that the framework incentivises providers to produce forecasts that are over-optimistic.

The argument goes that providers can’t possibly show that they’re worried about doing what they’re supposed to for students or OfS, because then they’d have to report in said worry, and then they’d be subject to further regulatory attention. Better to make the income side of the excel sheet match somehow.

And so when that happens – everyone is a little optimistic – in aggregate that adds up to a level of obviously unsustainable optimism, better put as someone at OfS saying well they can’t all be right.

If that is what’s happening, we then need to interrogate why, what the impacts might be on the sector and students both individually and collectively, and what might be done about that.

Street cred

One of the aspects in OfS’ guidance that it says it will look at when judging sustainability is the credibility of a provider’s projections.

If one said “we’ll grow international PGTs by 50 per cent next year”, I can see how that might raise a red flag. But for more modest optimism – which after all may well be based on ambition, or what worked well in the past, or robust performance targets for a team – we might argue that a framework principally designed to make judgements about individual providers’ risk of breaching a condition of registration is flawed. That’s because of the way in which it prevents OfS from formally admonishing minor acts of optimism that then add up to collective delusion.

Others might argue that providers that are somehow scared of telling OfS the truth about their risks just need to be both carroted and sticked towards doing so – “its better for you if you’re honest, we’ll be nice, and if not you’re in big trouble”. But I suspect that misreads the extent to which what OfS is told reflects what a governing body is told, which in and of itself reflects what senior managers are told, which in and of itself reflects what are being told by external help vying for a contract, or middle managers under pressure. The fear of telling a bleak truth upwards starts much earlier up the stream than posting a reportable event on the OfS portal, and it’s only recently that it’s started to matter so much.

There’s also little doubt that while the “first slowly, then all at once” thing looks like it’s both starting to engulf providers and OfS’ capacity, it’s not clear that earlier honesty would have made the difference. Perhaps you could argue that the Office for Students should have seen this coming earlier, and prepped up for a raft of inevitable failure – because in a free uncapped market for international students, once numbers start to contract (either for immigration or currency reasons) the whole point is that while some will win, many will lose.

But what all of that – and OfS’ recent financial sustainability update – all miss is what happens to provision as a result. Both OfS and ministers have made it clear that financial viability and sustainability are its number one priority right now – better put as “we want all hands on deck carrot and sticking providers towards restructuring earlier to avoid a messy provider exit later”. But what does restructuring early enough mean then for students?

Where’s your focus?

As I note above, Conditions D1 and D2 focus on financial viability and sustainability. There are then two other D conditions – one on a provider having the dosh to deliver on its contractual promises to students, and the other delivering on the regulatory requirements in OfS’ framework.

In less straitened times, designing a regulatory framework in theory in a meeting room in Bristol, you can see how a message of “don’t go under, and do what you said you’d do for individual students and students/society collectively” hangs together.

But once times become tight, the need to become financially viable inevitably trumps a focus on longer-term sustainability. That in turn inevitably trumps a focus on meeting every promise made to students and bearing down on grade inflation or delivering the targets in the APP. Especially when the press releases, the ministerial announcements and the calls are about money not experience.

The crucial thing is that provider interests are not always the same as student interests, individual student interests are not always the same as disadvantaged students’ interests, and “we need to not run out of cash” is not always the same as “we’ll ignore CMA and avoid accepting legal liability for a strike until a court tells us to”.

You can always argue that providers going under is bad for everything – but if in doing so you set aside or deprioritise the individual or disadvantaged student, you may as well not have the “we’re a student interests” regulator framing that OfS fanfared upon when coming into being.

As such the big question becomes what ministers are signalling is important (which implies other things are less so), what OfS then signals are important (which implies other things are less so), and then in turn what governing bodies and senior managers signal are important, which also implies other things are less so.

The signal not the noise

Like many others, in another bit of my life I’ve just been through a tortuous (and at times legal) eighteen month process of trying to get an education, health and care plan (EHCP) agreed for one of my children.

As in HE, the local authority has a series of legal duties. As in HE, we in theory have a raft of legal rights as a family. And as in HE, the local authority is strapped for cash – and while there has been recent recognition of the problem, it’s also the case that ministers have tended to stress local authorities’ autonomy to make prioritisation decisions, be more efficient and make bold decisions on delivery models.

These combinations – of legal rights that are attached to individuals, quasi-legal duties on providers over performance and public duties, and a government that holds (most of the) purse strings – are rife across public services. To begin with, they deliver efficiency and value for money for the taxpayer by encouraging responsibility at a lower level. But eventually they descend into a never-ending stream of least-worst decisions that day, and a profound lack of honesty, that both contribute to politicians being able to avoid a mismatch between funding and those rights and expectations.

It’s widely understood that local authorities don’t have the dosh to deliver on the EHCP framework as set out in legislation. But outside of collective muttering from the Local Government Association, it’s not as if mine has ever admitted as such, either to me or to the people of my county – at least unless formally inspected.

It’s widely understood that rationing of the budget and capacity that it has got is necessary, and that “well you could have spent a little less on X” won’t fix the fundamental problem of a set of duties being bigger than the funding envelope to deliver them. But because they’re legal duties, nobody can ever admit that rationing whose rights are met or which duties are delivered is going on – because that’s not officially allowed.

It’s widely understood that if local authorities have a range of duties, they should make decisions based on a mixture of objective assessments or need, and the local political priorities that manifest through democracy. But eventually, both of the above goes out of the window, replaced with making decisions based on risk – who’s bearing down on us, who could fine us, who could take us to court and so on. And the problem with that is that those who minimum legal rights are aimed at tend to be those least likely to be able to avail themselves of them if there is a problem.

And so in the end, that means that ministers keen to not have a council go under on their watch, and parents who can afford barristers to argue their case at a tribunal, are going to be the ones whose needs are met – while everyone else gets rationed out.

It’s not so much marketisation per se that does that – although the perversity of expecting geographically and socio-economically distributed public goods from a private loan scheme with little subsidy left where places are not rationed or distributed plays its part.

It’s that the “here’s all the rights and duties” and the “here’s not enough money” thing eventually causes the former to become a chimera – almost without anyone noticing.

What we know, what we don’t

OfS’ update report (which itself builds on previous reports) on financial sustainability is very much focussed on finances, rather than delivering a strategic assessment on whether providers in aggregate can really meet the promises made to students or the load and complexities of its regulatory framework. Do it know what’s happening to subject availability? Quality? The student experience? Closing a course isn’t even a reportable event.

The mood music has all been about restructuring and business model change – with only occasional buried mentions of the other half of the equation. OfS’ repeated promises on better enforcement of consumer protection law go unmet, over everything from contracts to fee increases. We’ve not seen any monitoring of performance against APPs for a couple of years – and quality is only being looked at in egregiously bad cases. TEF – and its wider agenda of enhancement – has gone eerily quiet. Student choice information is increasingly meaningless. And nobody seems to be keeping an eye on subject availability from the point of view of those who can’t or won’t travel.

Neither OfS nor ministers will want to admit that some students have got no way (and no information on which) to choose, and others won’t be getting what they paid for, and so neither in turn will providers. And nobody wants to admit how weak the protections are in the event of provider failure either.

Providers can then strip out promised pathways and module diversity relying on legal clauses designed for the odd staff member to go on research leave, not the wholesale collapse of breadth. Courses can close – and students get promised “teach out” that never pans out. Just as we saw over students’ rights during the pandemic, the system is subconsciously designed to punch down – and in aggregate, hopes that students don’t or can’t enforce their rights at the altar of financial sustainability.

Students don’t protest and staff don’t strike because from top to bottom, from OfS’ confidentiality over interventions right down to a course rep in an SSLC full of staff “at risk”, everyone has bought into the idea that drawing attention to the fire will mean that those recruiting to that university will find it harder to cheat the odds and beat the others. Governors don’t ask too many questions because having been tapped on the shoulder for being a member of the great and good, they don’t want to be associated with failure. And at every level, it’s not just that managers want to please up – they want to reassure down too.

The Office for Students is is ringing universities for “reassurance” conversations before sending in accountants…

…the i Paper reported last week. Reassurance is the name of the new game. And at every level, everyone gets to say “well no-one told me” as a result.

The worst thing about that EHCP process has been the constant feeling that the never-ending layers of corporate reassurance above – from every new caseworker to the council leader – have no incentives at all to call 999. Because then it would be even easier for people like me to take them to tribunal.

Everyone has choices in this scenario. Students and their unions could be drawing clearer lines about acceptable and non-acceptable cuts. Providers could be making it clear to OfS that they can’t meet the whole of Condition D – flagging problems with D3 and D4. OfS could be saying it to central government too – ideally publicly. But everyone has deep, deep incentives to do the opposite.

The Enron scandal of the early 2000s was not about outright fraud – it was a failure of organisational culture and incentives. It had, and existed in, a culture that prized the appearance of success. Employees, managers, and external auditors were incentivised to reassure upwards, painting a rosier picture of the company’s financial health than reality justified. Cumulatively, that led to concealment of massive risks and liabilities, which, when finally exposed, triggered one of the largest corporate collapses in history.

In Keir Starmer’s speech to Labour Conference in September, the announcement of a Hillsborough law to deliver a “duty of candour” was framed in a new era of honesty across public services about trade-offs, realities, admitting mistakes and levelling with the public. It was also partially about turning that cumulative reassurance logic on its head.

If it’s the case – that for the time being – the higher education sector can’t do what it promised, and can’t produce the public goods its regulator pretends it can, everyone should say so. Just as those micro decisions on optimism need to stop, the whole system needs to stop deciding tomorrow to do the least worst thing that day and hope that nobody above them notices. Instead, it’s time to level with staff and students.

Excellent piece.

“fear of telling a bleak truth upwards” hits the nail right on the head.

Not only in finances/student numbers. Not only in our institution. Not only in our sector. This fear seems utterly pervasive right now. Nobody wants to take the personal risk of being the bearer of bad news, and so we collectively sink.

In fact people nearer the chalkface often do tell the bleak truths upwards, but it doesn’t make much difference as it only takes one person in the command chain to filter them out. University SLT writes a strategy based on n% growth, to be achieved by n% growth in each Faculty, then tells each Faculty it expects a strategy for n% growth. Each Faculty handles this by writing a strategy assuming n% growth in each School, and tells each School to write a strategy for n% growth. Each School in turn assumes n% growth in each Department, and tells the… Read more »

This hits the nail on the head. Not only do schools / departments get asked for a strategy for n% growth, more often than not they have no control over / support from the levers that would be necessary to achieve this such as detailed market analysis, marketing / comms etc….

There is a phenomenon called the “Gray Rhino Effect” which might help explain the problem. The Gray Rhino effect refers to risks with a high chance of occurring and a massive impact if they happen, but we fail to recognize them as threats because we overlook their obviousness. It’s not that we didn’t see trouble coming; we just despise it. The term was originally coined by Michele Wucker in a book of the same name. The Gray Rhino effect is like a lot of other well documented cognitive biases that limit the ability of many leadership and governance teams to… Read more »