When it comes to those who are first in the family to attend university (or indeed those who are first to attend university in the UK), research tells us that we have to be careful to make sure that applicants understand the financial commitments that they’re getting into.

For example, last November Public First carried out polling for the All-Party Parliamentary University Group that asked about day-to-day living costs at university – accommodation costs, food and so on. One in five that would be “first in the family” figured they would end up spending less than £100 a week – a figure that halved for those whose parents went to university.

So, given that universities themselves are an essential source of information, advice and guidance about the costs of study, I thought I’d take a look at what the sector has been saying on the subject – particularly in light of the cost of living crisis, soaring inflation and record breaking food, rent, energy and travel costs.

Full disclosure on method here – I searched for the terms “cost of living” or “living costs” with the filter site:ac.uk on 31st July and 1st and 2nd August 2022. Where I found some cost of living of advice, I looked for any source for the figures and used archive.org to see if the advice has changed any time recently. By the time you follow some of the hyperlinks, some of the figures might have been changed or removed – I have screenshots.

Secret source

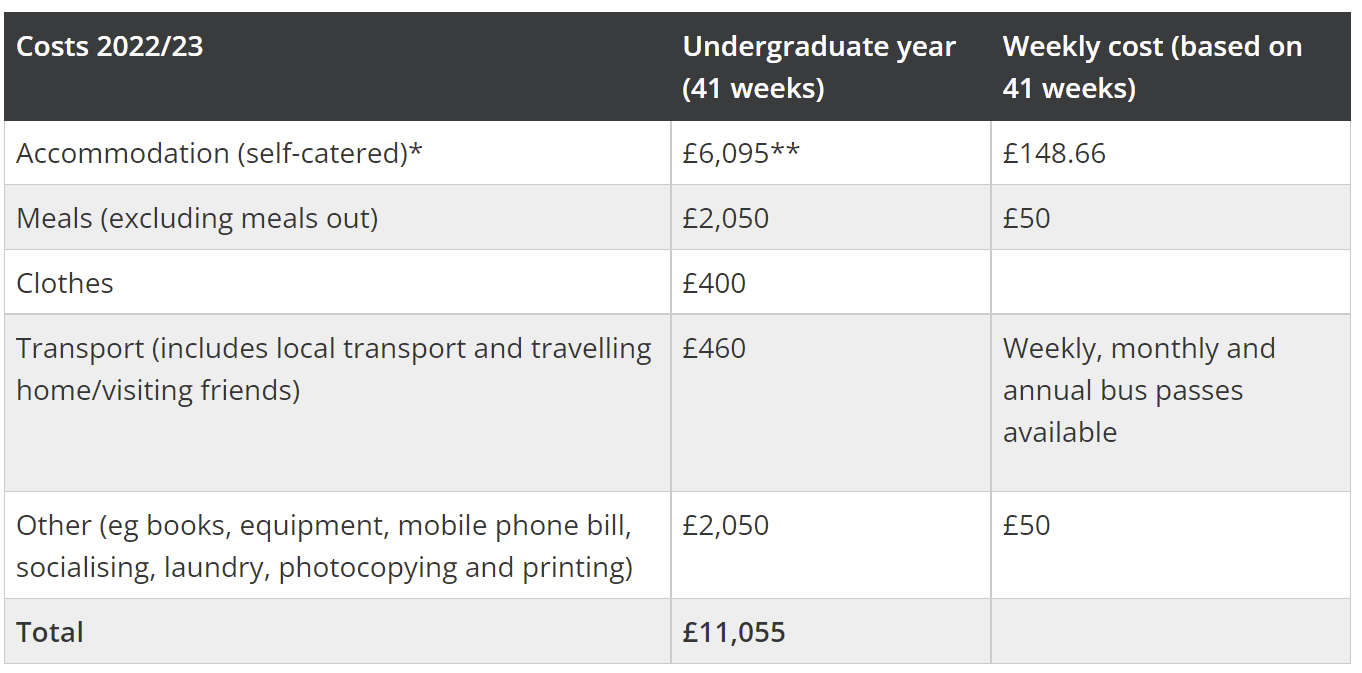

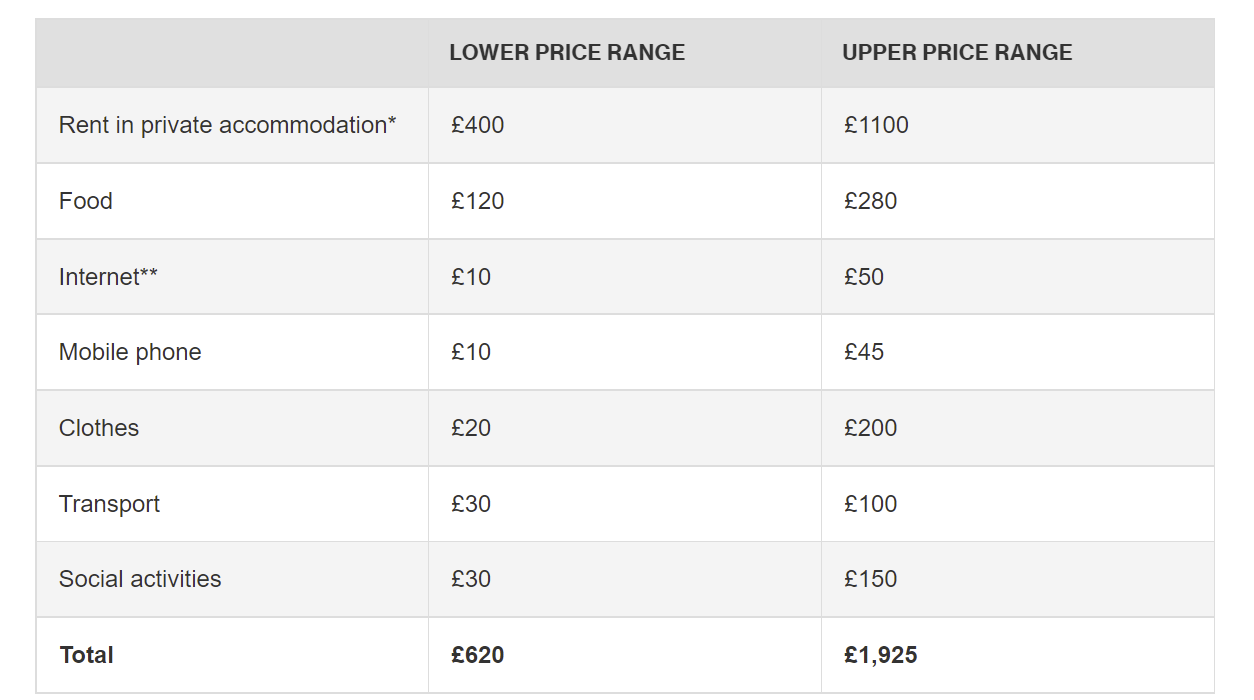

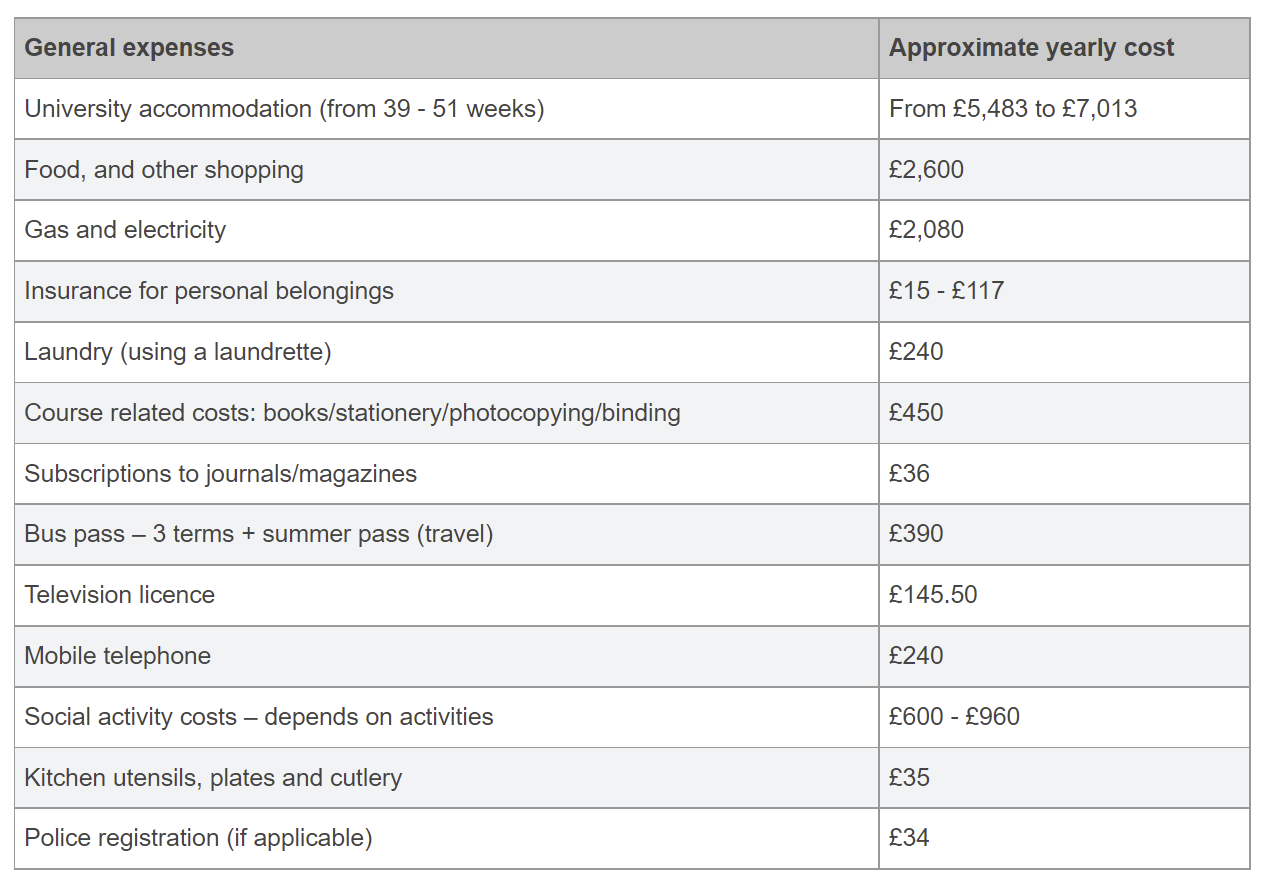

The first result is for the University of Manchester, where we find a set of estimated 2022/23 living costs for undergraduate students. It has been quoting the “average Manchester student” as spending £400 a year on clothes since 2014 – ONS estimates that consumer spending on clothing has doubled since then. For 2015/16, it had undergraduate course costs excluding tuition fees at £420 a year and “other” (mobile phone bill, socialising, laundry, photocopying and printing) at £1,600 a year. For 2022/23, it wedges those categories together and calls it £2,050. It doesn’t tell us where any of these numbers come from.

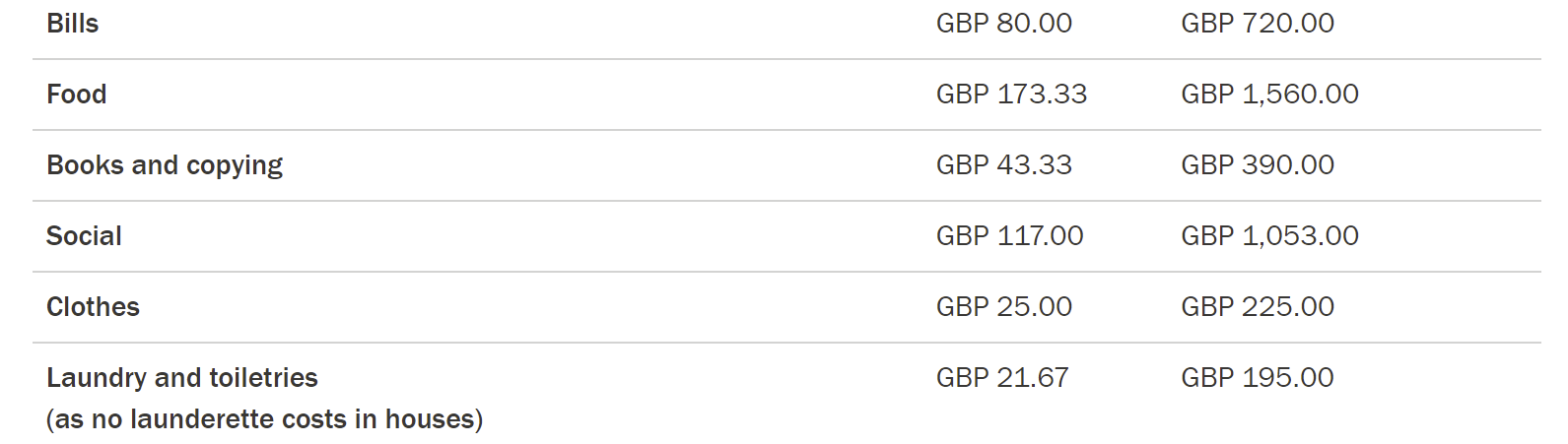

At Cardiff University, we are first told that Cardiff “has the fourth-lowest monthly rent of all the UK’s university cities” a claim grounded in the 2021 NatWest Student Living Index, which is not the most trustable bit of student costs research given it also tried to suggest that students in London were paying £9.10 for a pint. Looking at home domiciled undergraduates in private accommodation, Cardiff has increased its estimates for rent, bills and food since 2021 – although books and copying, social, clothes and travel have all been static since at least April 2021. Again, it doesn’t tell us where any of these numbers come from.

At Newcastle University, we are told that understanding the cost of living is an “important and often neglected” part of university life. Sadly the other thing that seems to be neglected is its information on the issue – all of its figures for cost of living have been there intact and unchanged since at least September 2020. We’re not told where any of the numbers came from.

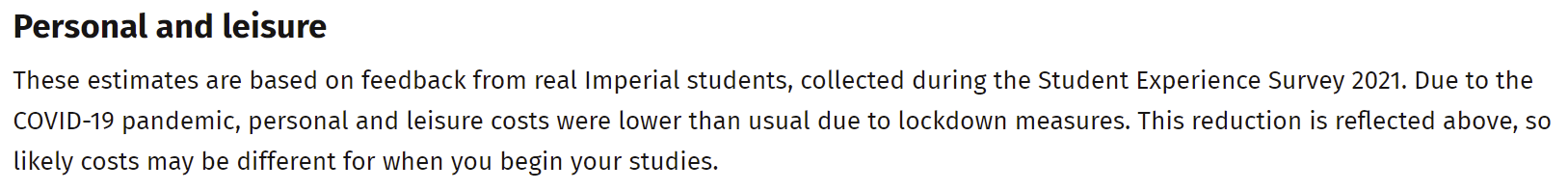

I was tempted to say well done to Imperial – it says its estimates give applicants numbers “based largely on averages” from its Student Experience Survey 2022 results. But buried later in the small print is a note that tells us that its “personal and leisure” estimates are based on feedback collected in the 2021 survey, when costs were lower than usual due to lockdown measures associated with the pandemic.

Same as it ever was

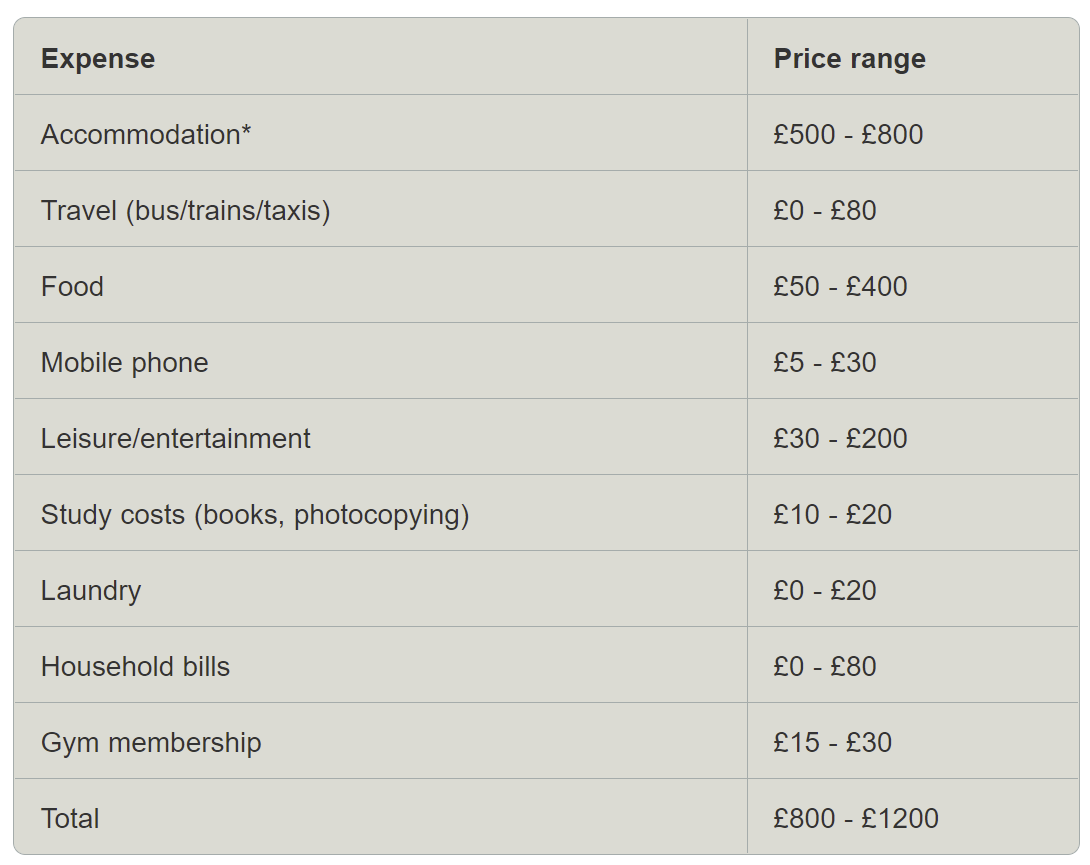

At the Bayes Business School (part of City, University of London) master’s applicants are advised to budget between £223 and £423 a month to cover “basic essentials” in London, including £10 a week for energy bills in the private sector. As a coincidence, when it was called Cass Business School all of the estimates were identical back in 2017.

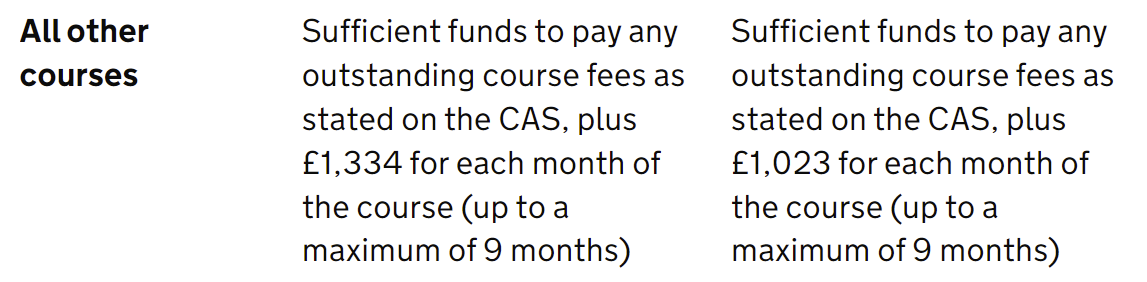

At King’s, applicants are told that to live to a reasonable standard in London, it currently estimates that students should allow approximately £1,265 per month for living costs in addition to tuition fees. There’s no source for that figure – although it just so happens to match the £1,265 quoted later on the page as the amount that UK Visa and Immigration (UKVI) requires students to have on entry for each month of the course. Sadly even that figure is wrong – it’s actually currently £1,334, with the figure that’s quoted actually from 2020.

A number of universities, incidentally, seem to use the UKVI figure as a magical guide to the cost of living. As I pointed out back in March, because the Home Office has only updated that living costs figure by 1 per cent for 2022/23, there is a material risk of seriously misleading international students about the affordability of the UK this coming year. Upsettingly, it seems to be a risk a lot of universities are willing to take in exchange for the tuition fee cheque.

Strathclyde advises international applicants to take into account the “annual increase in the UK cost of living”, which it says is “usually between 2-3%”. Those were the days. Swansea just tells us the average living costs for 2021/2022, which is one way of avoiding inflation. Herts has been advising students to budget £80 a month for utilities since 2018, which is another. St Mary’s (Twickenham) tells students to save money by “looking for student deals” – they’ll need to given St Mary’s also doesn’t seem to have updated its estimated costs for those in private and off-campus renting since 2019.

Timeless classics

Durham says that it “makes every effort” to ensure that the information published on its living costs page is accurate – although it hasn’t updated its estimates for over a year. UEA has been giving applicants the same cost of living figures since at least September 2020. Kingston hasn’t updated any of its figures in over a year, Coventry (London) has cost of living in the same place as it was in February 2021, and the University of Leeds tells us that the “Which? Student Budget Calculator” is a useful tool to help create a budget and manage finances, even though its figures don’t seem to have been updated since January 2020. SOAS hasn’t updated its estimates for living costs in London since 2016, and the University of Liverpool has the same figures it had back in 2020.

Surrey has updated its figures since 2020 – it has slapped a £1 onto estimates for weekly travel, but it’s left every other figure for student costs the same. Ignoring rent, Exeter has costs for students in self-catered accommodation as identical to those it had in 2017/18, save that its guess on Phone and Internet is actually £34 lower! The University of Sheffield was telling students that utility bills in private housing would be £12 a week in 2019, and still is here in 2022, and at Birmingham City the only thing that’s changed since 2015 is the cost of its own halls.

Poor information has costs

Basically, with a handful of exceptions, the information I found was breathtakingly inadequate – poorly sourced, rarely updated and almost universally “fingers in years” about the rocketing rate of inflation we’ve seen this calendar year. It’s just not good enough, and I’d urge every university in the UK to review the information they’re putting out now to address the dangers of convincing students that they can afford higher education when they can’t.

I’ve thought for some time now that as providers of information, advice, and guidance (IAG), universities ought to be subject to some regulation over what they tell students in that space. I don’t know if the problem here is accidental – a lack of effort in updating numbers that results in what I can see – or something more sinister about not putting students off before they become on the hook for the fee.

I do know that if OfS spent more time telling providers to update and publish information like this rather than developing plain English summaries of access and participation plans that students still won’t read, students would probably be better off. And obviously it would be even great if if it told providers that promised a £1,000 bursary to the poorest in 2019 that that figure needs uprating for inflation here in 2022.

Of course this also all highlights the lack of accurate sources of intel on the subject – underlined by the fact that in England and Wales it’s been almost a decade since the national Student Income and Expenditure Survey was in the field. Now it’s been done again, the results can’t come quick enough – and should be used as a source of this sort of stuff, rather than the “survey from a Pub Chain said we were third for curries” nonsense that I keep coming across.

I am especially worried, by the way, about students who are looking at the coming academic year and thinking they can’t afford it but are trapped in housing contracts for 2022/23. Facilitating them to find someone else to take on the commitment now will be better than them crossing fingers and ending up evicted or in court in December. The sector coming out strongly for the renter’s reform proposals that would address being trapped in this way would also help. And as such, dropping out for financial reasons – or “sensibly pausing” as I prefer to call it – should be encouraged, not finger wagged at by regulators, ministers and universities.

But generally, the sector should be redoubling its efforts to make clear to students and their families both how expensive being a student is, and how expensive it’s about to get. It is, after all, easier to get angry and organised about poverty before you’re actually experiencing it. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again – evaluating the efficacy of cost of living and maintenance support on application and drop out rates is immoral, hopelessly laggy, and ignores the real truth – that those from the poorest backgrounds will eat dirt to realise their educational ambitions.

Sadly, while eating that dirt and getting that 2:1, they’re probably not engaging in the types of wider student activities that will give them the friends they need in the harder times, the first they deserve if they had the support, or the career they could get if they could build the skills, networks and confidence that higher education is supposed to provide. The very least we can do is warn them.

I agree with all of this, but I’m torn – I’m not sure in the current headwinds it’s moral to enrol students who are likely to drop out for financial reasons (through no fault of their own) and allow them to build up more debt.

It depends on who drops out and their likelihood. If it’s certain groups of people, in particular those on low income, then we can pull the policy levers to help those individuals – for example by bolstering institutional bursaries to meet the rises in costs. It’s far more immoral to not enrol students, impacting their outcomes long term, because institutions and the sector are unwilling or feel wary to pull those levers.

Whilst flawed, at least the ‘old’ Unistats/Discover Uni return (the KIS), required provision and publication of estimated accommodation costs, location specific. If anyone was actually using the Discover Uni site, it might be worth thinking about what is the most valuable information to potential applicants…