The expansion of university estates over the last ten years is connected to the massification of higher education.

But expansion is also linked to marketisation – as HEIs compete for students in an environment where income depends on student numbers. What do these newly built HE spaces tell us about the meaning and connected activities of teaching and learning and working in higher education? And how is HE space experienced by the staff and students who use it?

Building universities for the future

It makes sense to connect the recent expansion of HE estate to a strand of educational policy that affected schools and colleges in the “Building Schools for the Future” (2005-2010) and “Building Colleges for the Future” (2008-2009) initiatives. Both these earlier policy initiatives produced buildings that express a particular ideologically-inflected vision of what educational space should look like.

The instrumentalist purpose of education that underpins this vision maps has characterised the last quarter century of education policy in England, and more widely. In further education colleges, new buildings have proved challenging environments for staff and not always conducive to teaching and learning.

But unlike the new schools and colleges, HE new builds do not originate in central government’s determination to modernise the nation’s educational estate. This expansion is more obviously read as institutional responses to a competitive environment. These new-builds seek to attract students by the facilities they offer, but also and more nebulously, by the aura and allure of their glazed façades and bustling atria. To that extent, new build HE estate communicates important messages about the commodification of HE.

Recent research I carried out with Dr Fadia Dakka at a West Midlands modern university contrasted the rhythms and feel of three of its campuses. Data from each campus – one newly built, the second recently refurbished and extended, the third built in the early seventies (and now demolished) – provided some startling insights into the emerging meanings of the new HE architecture, and the way it is used and experienced.

Go to the foot of the stairs

By using walking interviews and timelapse video we were able to capture the rhythm of campus libraries, external entrances and the main social learning spaces as well as the feelings of staff about particular spaces.

For one member of staff in the new-build campus, a significant space was the stairwell designated as a fire escape route. The stairwell space provided quiet and stillness: qualities that were not easily found in the participant’s staffroom. For him the space facilitated intellectual labour: it was a place for thinking. He commented that the same space was often used by Muslim students for their midday Zuhr prayer.

The necessity of entering a stairwell to find a space for reflection in an HE environment suggests a significant oversight on the part of the building’s designers. There is also a suggestion that the new-build encodes HE work as social and interactive at all times.

The new-build campuses were also characterised by distinctive collective spaces: grandiose balconied atria, social learning spaces, and libraries. Timelapse video of the social learning spaces showed a ceaseless ebb and flow of staff and students. In our analysis, social learning spaces and atria play a particular role in the formation of student identities. They are institutionally constitutive: places that seek to manufacture the “belonging” that HEIs need to conjure up for favourable NSS scores. Their design includes multiple vantage points as they make students visible to each other as subjects caught up in the flow and illuminated by the aura of the HE experience.

Learning spaces

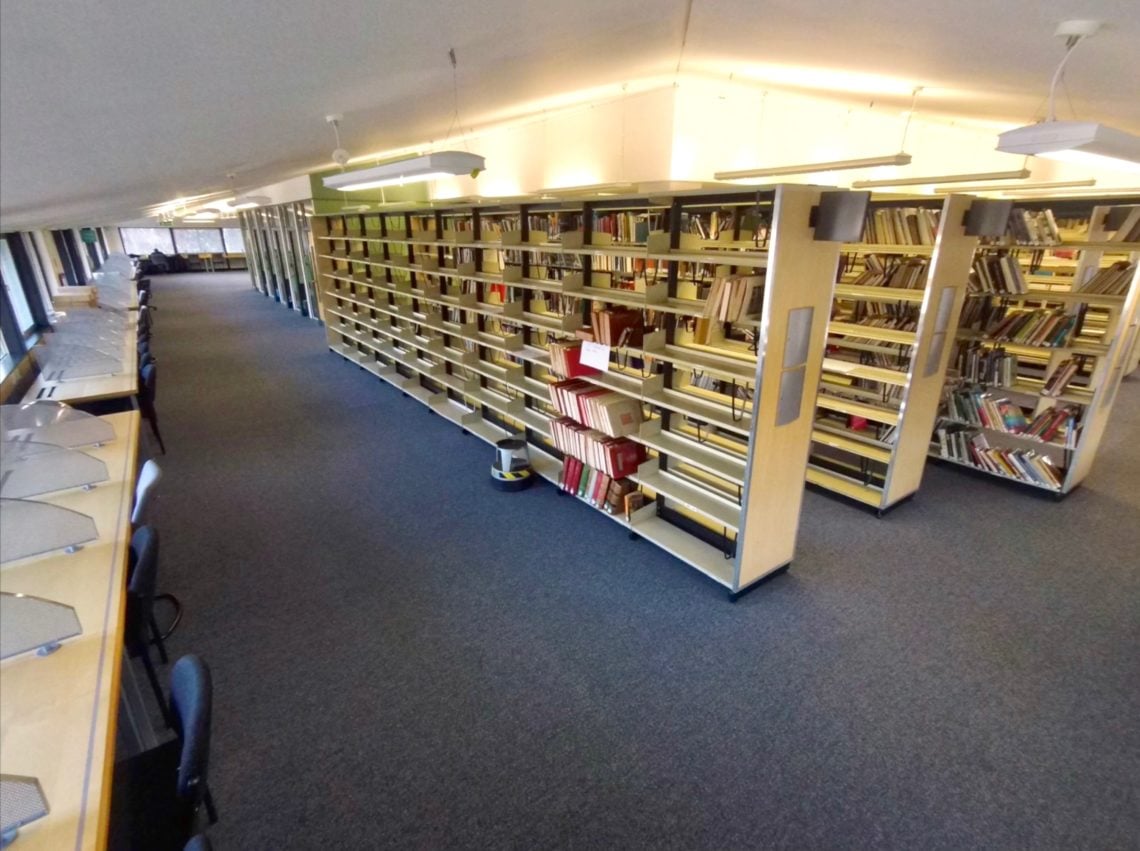

Like atria, social learning spaces only make sense when they are peopled. Like shopping malls, they are dependent for their meaning on footfall and their space is produced by movement, exchange and interaction. They advertise energy and motion. In contrast, the library in the soon-to-be-abandoned campus had a haunted feel suggestive of high streets that have been abandoned in favour of new shopping centres.

Teaching spaces in the new-build campuses were, to a large extent, anonymous and interchangeable. Staff had been requested not to damage paint by sticking anything on the walls. Classrooms were often generic rather than subject specialist. Generally, they had at least one glass-wall which sometimes interfered with the acoustics.

This provided a useful contrast with the buildings on the older campus which were at the end of a forty year lifespan. The classrooms there were heavily marked with a patina of use: students’ work and staff displays covered the walls. Teachers had personalised their classrooms and workspaces and literally dressed the walls with material produced by teaching and learning.

Understanding how we use space

Henri Lefebvre’s triadic conceptualisation of space proposes three interconnecting descriptive terms:

- conceived space – exemplified by architectural design,

- perceived space – practices and behaviour linked to particular spaces,

- lived space – the space to which individuals bring their own meanings, values and action.

The Lefebvrian view is that these are shaped by dominant interests but that space does not only act upon human beings – people also “produce” space in the ways they use it. There is a sense then that in new buildings, teachers and students have actively to work against the conceived space on offer, to tarnish its aura with use, to act upon it to produce space that is de-commodified.

A member of staff in the old campus sought out a space on the top floor of a half empty building which afforded a view over the neighbourhood. This was the campus housing the School of Education which was relocating to a leafy suburb on the south of the city. For this participant, the quiet was not an escape but rather, provided historical echoes from a teaching experience in a further education college in the late 1990s. In a similar competitive and marketised setting, enrolments had fallen and the college had felt deserted. This immediately preceded a funding crisis, redundancies and ultimately the relocation of the college to new-build premises.

The significance of the space in this case relates to a historical sense of the bigger cycle of change, including the abandonment, waste and renewal that marketisation brings with it. That HE is caught up in a wave of policy and that this is having an impact in educational settings and on the careers of the people who work there were experienced as material phenomena. The places in which we are educated stay with us; they mark us.

We need to remember that, in time, these HE new-builds will acquire the same patina of teaching and learning that made the old campus feel so familiar and well-used. The teaching and learning that takes place there will, by attrition, tarnish their shine and one day they will also seem tired and dated. These new buildings seem to signify that the zombie hegemony of neoliberalism is still animated. But their current allure will fade. We can only hope that the commodifying view of HE that positions it as mainly or exclusively a provider of human capital fades with it.

Having various old and new buildings on campus it’s clear most Universities have plenty of cash to splurge of massive architectural monstrosities, from wavy walls, loosing 5-10% of usable space in offices, to award winning ‘play-school’ colour scheme’s devaluing the research departments efforts to not just be serious about it’s work but also to look serious in the process, along with towers with huge but unusable atria not easily adapted to other uses in the future, one has to question, are the ‘vanity projects’ getting out of hand? It’s interesting just how many Fire Escape stairs, and disabled toilets, are… Read more »

@N You say “most Universities have plenty of cash”. It may look like it at face value but dig deeper and you will find that many of them are leveraged to the hilt taking out huge loans and other financial obligation to feed the expansion frenzy. Note that the trebling of student fees never completely compensated for the reduction in public funding imposed on universities in the first place. The uncapping of student numbers has not helped either as some institution hoover up more students than others that are left in serious deficit. The fight over the USS pension fund… Read more »