From a university finances perspective, it could definitely have been worse.

The decision of the Westminster government to freeze undergraduate fees in England at £9,250 a year for the remainder of this parliament makes good political sense.

It avoids the risks of making a larger proportion of university funding subject to the state of the public finances, as the Augar report had essentially recommended when it suggested that fees be reduced to £7,500 and topped up with public funds.

And it avoids the tricky politics of raising fees and graduate debt – even if only by inflation – which is always a difficult sell but even more so at a time of rising cost of living, increasing demand for a skilled workforce, and with the next general election in view.

Buckle up

If history is anything to go by though, the overall financial settlement does push more of the cost of the student finance system on to incoming graduates, and while there could be a political cost to that decision, it’s likely to be much smaller than the public consternation that a fee increase would incur.

But while £9,250 in the public view still looks like a significant chunk of change for a year of university study, from a university finances perspective, it means the belt-tightening that has been a feature of the second half of the past decade is set to continue and intensify.

Writing recently on Wonkhe, Universities UK president Steve West said,

With growing inflation pressures, it’s not an exaggeration to say that some universities may simply not be able to afford to continue providing the breadth of high-quality courses that UK universities are internationally renowned for.

The recent assessment of the regulation of university finances in England from the National Audit Office (NAO) makes some salient observations about why – despite the absence of a serious Covid-related shock in the form of loss of student numbers that was originally feared – the financial outlook for the sector is a cause for concern.

The numbers of institutions whose budgets are in deficit is rising. This needn’t be a cause for concern in any single financial year – revaluation of pensions liabilities can cause there to be a one-off “accounting adjustment” – but, the NAO says, of the 80 institutions that posted a deficit in 2019-20, 20 have been in deficit for at least three years.

A handful of providers in England are facing short-term risks to their financial viability and sustainability. The NAO says that in 2020-21, 33 providers had forecast liquidity (ie. the amount of cash on hand available to keep things running as usual) below 30 days.

While most universities are fine in the short term – and those that are higher risk are unlikely to collapse barring a major financial crisis – there are medium- and long-term structural challenges. The rising cost of pensions is one, that public funding for research does not account for the full economic cost is another. And the inflationary erosion of the purchasing power of that £9,250 fee, plus the additional expense of managing the pandemic and the associated costs of reforms to learning and teaching as a result means that most home student teaching isn’t exactly high margin either.

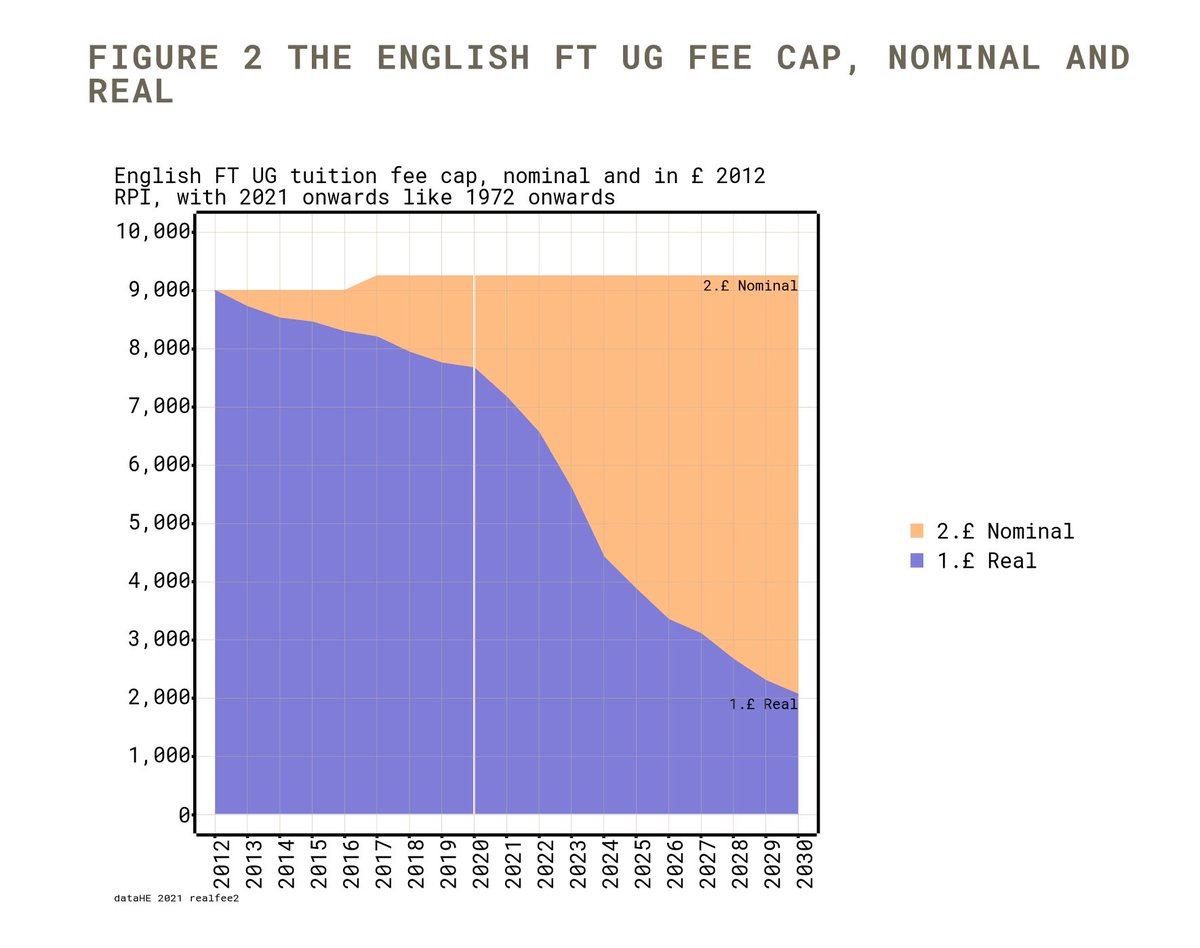

Here’s a worrying graph to put all of this into context – shared by Mark Corver of dataHE at last year’s Wonkfest – showing the “real terms” value of the headline fee year on year.

Tough decisions

Now it’s possible to overstate all of this – compared with much of the public sector that is facing similar structural challenges (think the NHS dealing with an ageing population), the university sector remains comparatively well funded.

But that’s not a great deal of comfort to the university managers and staff forced to make tough decisions about where to put increasingly scarce resources.

And whatever the Office for Students’ definition of value for money – something the NAO report felt could be tightened up – universities will be thinking hard about which kinds of financial controls will ensure that money is spent on the right things. And that, of course, is very much subject to debate (to put it mildly).

Let’s not forget, as well, that while the next three years look fairly clear now, the future after that is uncertain. There will be a general election probably in 2025.

The current government has pledged to roll out the Lifelong Loan Entitlement from academic year 2025-26, and it is very unclear at this stage what impact that will have on universities’ ability to make financial plans.

At a very high level, in theory more students would be able to register for shorter courses, or even single modules, rather than for traditional three-year courses. But would they?

Challenging outlook

I spoke to Andrew Bush, director of education, skills, and productivity at KPMG, to try to think through the implications of a new funding system on universities’ finances.

“The likelihood of a big bang change in 2025 where we see, say, half the student population switching to a modular way of studying feels unlikely,” he says. “When student loans were first introduced, and subsequently increased to £9,000, the communication and promotion efforts to help prospective students understand the new funding system were not extensive or sustained, so that could slow down the transition.”

But there are risks, too, with a new system that could produce greater unknowns. “If you look at the current balance of programmes, there is a lower quantum of students going through higher technical qualifications, and we don’t know what scaling that up does for retention or completion compared to a three-year degree,” Andrew says. “And that would have implications for both financial planning and securing income flows.”

And, Andrew adds, different institutions have different capacities to respond to the changes. “Some parts of the sector are more insulated from financial shocks because of their size, the diversity of their income streams and/or their financial strength and the programmes on offer but some others might be working on a small scale, delivering a narrower range of activities or have a portfolio or position that makes recruitment tricky,” he says.

In a new world of delivering volumes of bite-size learning (modules), it might not be the case that you can always have a critical mass of students that can make something sustainable, and there might come a time when the government has to intervene to support the continued delivery of certain provision in particular areas.

We both agree, sagely, that the future outlook is challenging – particularly when inflationary pressures are considered, which will affect both the real terms value of the headline fee and the value of any reserves that universities have.

But, Andrew points out, universities have long experience of managing difficult financial weather. The priorities may change but the process of making difficult decisions has not. Currently, with challenges from both OfS and DfE over quality, student outcomes are likely to become what Andrew calls a “non-negotiable” in the sense that activity that demonstrably contributes to those outcomes will be prioritised for resourcing.

There will be other questions, too – the level of cash reserves required to mitigate future financial turbulence, whether to prioritise investment in on-campus estate or in digital technology and infrastructure, and trying to find ways of controlling rising costs – some of which are not directly in the control of individual universities.

Put like this, it’s all very sanitised but there’s no question that some of the challenges universities have been facing over resourcing are set to continue – and where resource is at stake feelings can also run high.

“You can’t just think about finances in isolation – you have to think about staff and students as well,” Andrew says. “If more savings and reconfiguration are required, that will likely impact staff morale. Demoralised staff and disenchantment are likely to have a bigger impact on student experience and the metrics this affects. Whatever financial challenge and change comes along, you have to remember how critical staff are to the success of institutions.”

This article is published in association with KPMG.

“Andrew calls a “non-negotiable” in the sense that activity that demonstrably contributes to those outcomes will be prioritised for resourcing.” And those that do not we expect to be cut off. This article talks about 2025 but there is a good chance that at least a couple of big names need to seriously restructure or merge within the next year or so – one London University has deep structural issues with academics teaching hobby horses to five students – an unsustainable model but one their governance does not allow them to fix quickly enough. ” The rising cost of pensions… Read more »

This article takes the long road home. The graphic says it all. Overall, there will be fewer staff teaching more students per staff member, in some mix of in-person and online. Universities that have more diversified and sustainable income streams will have less extreme SSRs. If institutional rigidities (nice euphemism, don’t you think) can’t adjust the ratios quickly enough, then they will fold/be merged/be sold to private equity firms that will do the cutting.