Medieval England was full of guilds – chartered bodies often relating to a particular trade – which gave members rights.

One such was the Society of Merchant Venturers in Bristol: although chartered in 1552, it traces its lineage back to the thirteenth century with mention of a guild of merchants in the city. The society had some sort of monopoly on maritime trade “beyond the seas”, which was clearly advantageous to the society’s members, and the society and Bristol prospered.

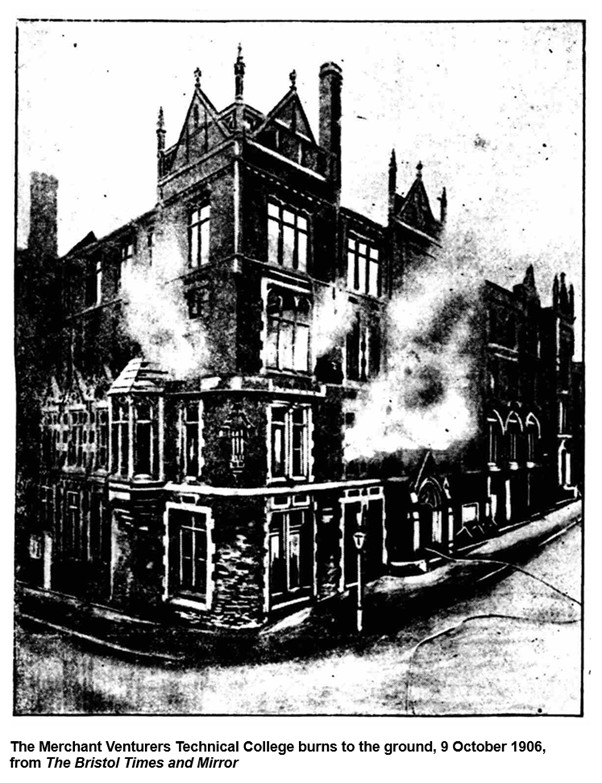

In 1595 the society established a school for mariners’ children. Over the years this would have developed; and in 1894 it was re-founded as the Merchant Venturers’ Technical College, with very fine new buildings, including forced air heating and ventilation systems. The college burned down in October 1906 – “reduced to a mere shell”, in the words of the Western Daily Press.

In 1909 University College Bristol received a royal charter, and became the University of Bristol. I’ll write about this another time, but for now, let’s note that the engineering section of the Merchant Venturers Technical College became part of the faculty of engineering of the university. This shows that it must have been of a reasonable standard; I wonder also if the fire, and the need to find new accommodation, played a part.

After the second world war, responsibility for the college transferred to the local authority. The two sites it then occupied became two different colleges: the Bristol College of Commerce at Unity Street and the Bristol College of Technology at Ashley Down. On 31 August 1949, just above an article celebrating the possible return of clotted cream from Devon, the Western Daily Press noted that courses offered by the College of Commerce ranged “from shorthand to shipbroking, languages to librarianship, and export to general education.”

Further change came in 1960, when the College of Technology split into two: the Bristol College of Science and Technology, and the Bristol Technical College. The former moved to Bath in 1965, becoming the University of Bath. And that is a story for another day.

And now the era of the polytechnics was here, and Bristol Polytechnic was formed. The College of Commerce and the Technical College were joined in this by the West of England College of Art. And the technical college split one more time: the Brunel Technical College offered lower level programmes; the higher level activity became part of the polytechnic.

As far as I can tell, this latter college had its roots in the Bristol Academy for the Promotion of the Fine Arts, which seemed to have admitted its first students in something like 1844, and was certainly involved in seeking tenders for a new building in 1855. It wasn’t one of the first government schools of design, although it appears to have been modelled on the same principles. In any event (and if I am wrong about this college, please do correct me in the comments!) it was by 1969 well established in Bower Ashton.

The nascent polytechnic was spread over several sites in Bristol, and in 1970 plans were announced to develop a campus in Frenchay, at Coldharbour Lane. Over time much of the activity of the various campuses would move to Frenchay, but for now it was just plans: the campus opened in 1975.

We now need to go down another historical byway: in 1976 two colleges of education were incorporated into the polytechnic. These were the Gloucester and Bristol Diocesan Training Institution for School Mistresses, founded in 1853 and latterly called St Matthias, and Redland College, an emergency teacher training college established in 1947. There’s an excellent brief history of St Matthias on the university’s website, including some great stories.

In 1992 the polytechnic – along with all others – was given university status and became the University of the West of England. A familiar tale of rebuilding an campus consolidation took pace, with the St Matthias site ultimately closing; the aggregation of city centre sites into one city centre campus; the growth of activity at Frenchay, and the establishment of a campus in Swindon. In 2012 there was an ill-fated attempt to create a stadium to be used by Bristol Rovers and the university, but this came to nothing other than legal arguments with Sainsbury’s.

UWE is now the thirteenth largest UK university by student numbers (2023–24 HESA data).

And there we have the UWE story, or at least one telling of it. The Merchant Venturers Technical College is unique, I think, in having given rise to three different universities. And, as the Brunel Technical College still exists as part of the City of Bristol College, and as the City of Bristol College has a university centre, there’s always room for a fourth to be created.

The card was sent in 1988, addressed to David, c/o Mrs Williams, at St Martin de Porres school in Luton. David was Mario Morby’s father; Mario had cancer and was collecting postcards to try to get a world record. The LA Times has a good write up; happily it seems that Mario survived the cancer, and got into the Guinness Book of World Records.

Here’s a jigsaw of today’s card for you to enjoy. And a bonus jigsaw of the St Matthias campus which is, frankly, quite challenging.

Hugh, all correct (apart from the Swindon campus, I think). When Bristol Polytechnic became UWE in 1992 I invented a family tree for a THES (as it then was) advert in a special supplement featuring all the post-92s, in an attempt to differentiate UWE from all the places advertising “the name’s changed but the high quality stays the same”. The family tree (which did indeed start from the 13th century Navigation School) survived for many years in UWE publicity materials, and may still continue for all I know. (https://www.uwe.ac.uk/about/our-history#a120b4699-9b47-4eec-91bb-21ad6e32bf42) The best advert in 1992 was from Teesside Poly, who already… Read more »