Salutojn el Londono! (That’s “greetings from London” in Esperanto, in case you were wondering…)

Back in 1826, there were two universities in England – Oxford and Cambridge – and both required people (which meant only men at this time) to subscribe to Anglicanism to be registered as a student. For radical London this was not an acceptable state of affairs, and in February the University of London company was established, with shares costing £100 each. The first students were admitted in 1828.

But it was not legally a university, of course, even if it had the name. And its establishment was a provocation: it was not only radicals who thought there should be a university in London, and the proponents of what would become King’s College, a thoroughly Anglican institution, were also active.

The compromise was the establishment of the University of London in 1836 as an examining and degree awarding body, with two associated institutions: King’s College and what was now known as University College London.

Oh, Jeremy Bentham…

You may know that Jeremy Bentham is associated with UCL. If you believe the stories, he founded the college, and is recorded as present at every meeting of the governors, because his preserved body is wheeled into the room. Sadly this is only tangentially true.

He didn’t found the college, although he was a shareholder, buying his share after the initial launch. But his ideas were absolutely behind the college’s launch.

He isn’t present at every meeting of the governing body. He’s never been a member. But, gloriously, he is still present in the college. His will stipulated that his body be preserved as an auto-icon, and that:

If it should so happen that my personal friends and other disciples should be disposed to meet together on some day or days of the year for the purpose of commemorating the founder of the greatest happiness system of morals and legislation my executor will from time to time cause to be conveyed to the room in which they meet the said box or case with the contents therein to be stationed in such part of the room as to the assembled company shall seem meet.

His auto-icon was given to UCL in 1850, and currently sits in the entrance to the new student centre. Here’s a picture of your correspondent with Jeremy, taken in September 2022. Bentham is the one in the hat.

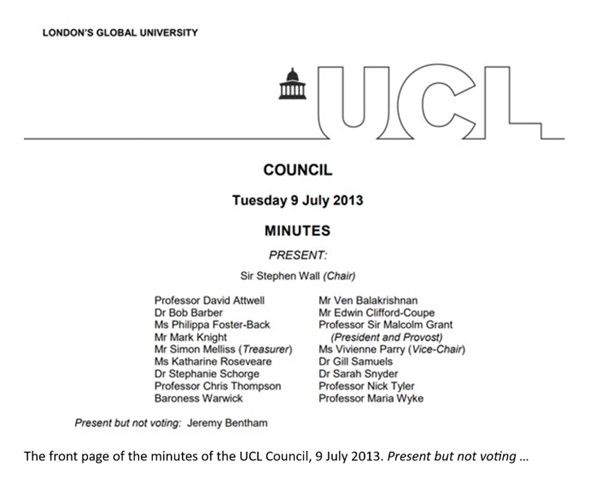

And, as a last word on Jeremy, he has been recorded as present at at least one meeting of the governing body.

On 9 July 2013, at what was provost Malcolm Grant’s final meeting, the auto-icon was present, and recorded as so in the minutes. Magnificent.

Governance types may want to ponder whether he would have been counted towards quorum had circumstances necessitated.

London calling

The University of London has a complex constitutional history, being at different times an examining only body, a collegiate university, and now a (loose) federation of colleges – but from 1905 to 1979 University College London was subsumed within the University of London itself. An act of 1905 made this happen; an act of 1979 undid it and restored to UCL its corporate autonomy. And to be fair to the parliamentary lawyers, the preamble to the 1979 act has a very good potted constitutional history of UCL up to that point!

Suffice to say that UCL has grown in size and grew in reputation. It grew organically, and also by incorporation. Here is a reasonably accurate list of the former University of London colleges and institutions which have become part of UCL. So far.

- Institute of Archaeology (1986)

- Institute of Laryngology & Otology (1988)

- Institute of Orthopaedics (1988)

- Institute of Urology & Nephrology (1988)

- Middlesex Hospital Medical School (1988)

- Institute of Child Health (1995)

- School of Podiatry (1996)

- Institute of Neurology (1997)

- Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine (1998)

- School of Slavonic and East European Studies (1999)

- Eastman Dental Institute (1999)

- School of Pharmacy (2012)

- University of London Institute of Education (2014)

Famously, UCL and Imperial did not merge in 2002. But UCL has expanded eastwards, with a new campus on the 2012 Olympic site.

Famously

UCL has many famous names associated with it. A particular favourite of mine is Freddie Ayer, Grote Professor of the Philosophy of the Mind and Logic at UCL from 1946 to 1959, after which he moved to Oxford to be the Wykeham Professor of Logic at New College. He was also an MI6 agent during World War 2.

In 1987, after he had retired, Ayer found himself at a New York party. Mike Tyson, the boxer, was hassling Naomi Campbell, at that time a relatively unknown model. Ayer intervened. Tyson reportedly asked “do you know who the f**k I am? I’m the heavyweight champion of the world!”. To which Ayer replied, “and I am the former Wykeham Professor of Logic. We are both preeminent in our field. I suggest that we talk about this like rational men”. And while they were talking Campbell was able to get away.

Infamously

UCL is not without controversy and problems. One such is its links with eugenics, the nineteenth century movement which sought to breed the most superior humans, ideas which were discredited scientifically and became associated with Nazism and racism.

Francis Galton – statistician and promotor of eugenics – had founded a laboratory at UCL in 1904. A 2018 inquiry by UCL into its historic links with eugenics, which had been established because of the realisation that between 2014 and 2017 it had hosted an annual conference linked to eugenics. Lecture theatres and labs were renamed, exhibitions and public education campaigns went ahead, but the majority of the committee of inquiry would not sign off the final report, as it did not cover the 2014–17 conference.

Speaking in tongues

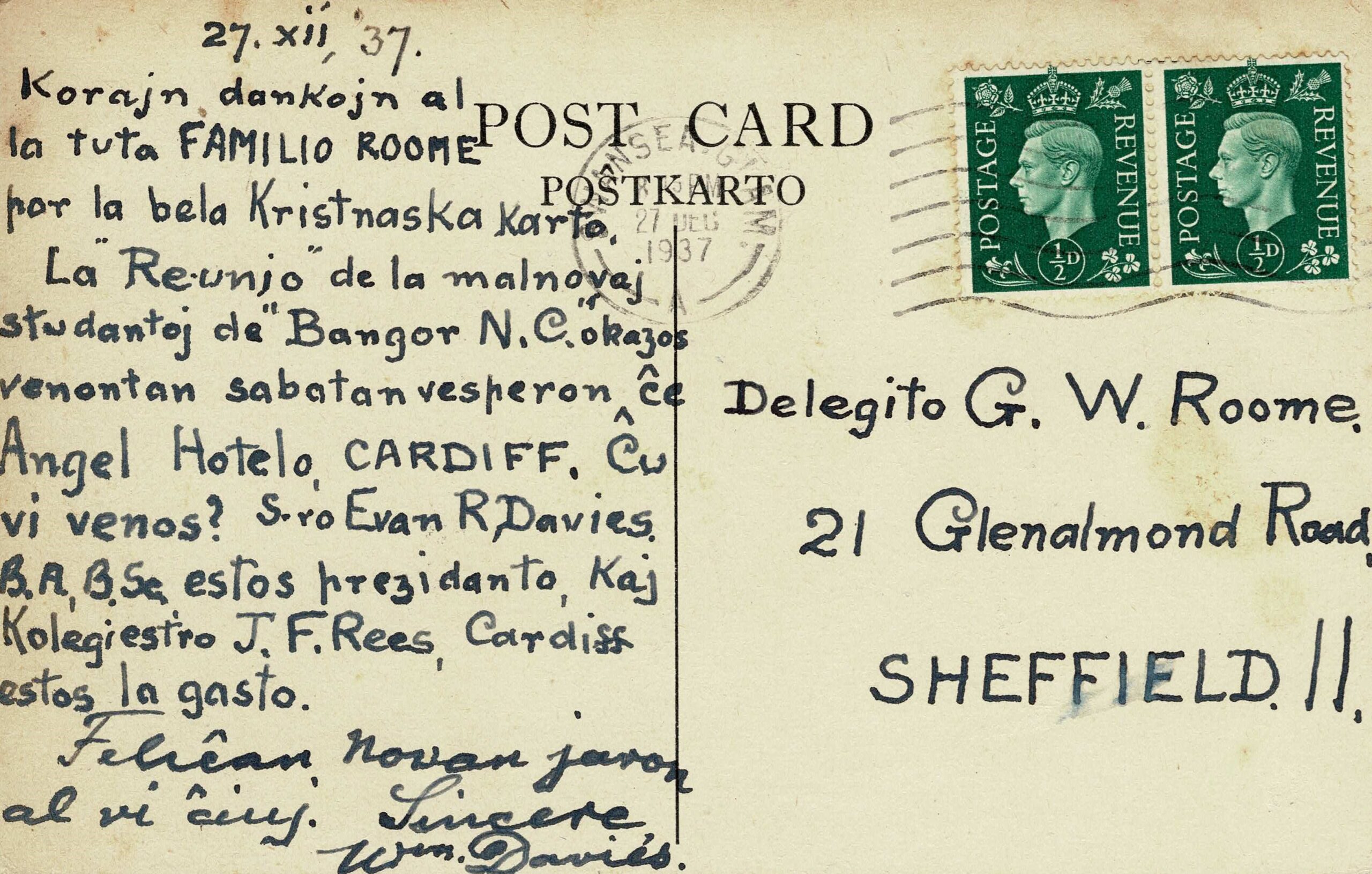

The card itself was produced to promote the 1938 World Esperanto Congress.

Esperanto is an unusual language in that we know when and by whom it was created: Ludwig Zamenhof, in 1887 in Białystok (then in Russia, now in Poland). Zamenhof dreamed of a world without war, and believed that better communication would reduce tension between nations. Esperanto was his creation: a language which would enable people from different nations more easily to understand each other.

Esperanto is estimated to have between 30,000 and 2,000,000 speakers. It derives much (but not all) of its vocabulary from European languages, and has a very simple language structure. Both Hitler and Stalin were against it, so it must be a good thing. An annual congress brings together Esperantists from across the world; the 1938 one at UCL was attended by 1,602 delegates, which is not bad going for a university’s summer conference business.

The card was sent in late December 1937 from Swansea to Sheffield, and, gratifyingly, is written in Esperanto. See how much of it you can understand, without reaching for a dictionary or Google translate:

If you want to know more about UCL, let me point you at the wonderful book the World of UCL, which is available free to download from UCL Press. Edited by Negley Harte (who back in the 1990s was the University of London public orator, and a very witty man), John North and Georgina Brewis, it is a very readable and, frankly, more reliable source of information than this blog.