Greetings from Oxford!

Many – perhaps even most – universities have a statue or two. But few have a statute which is as troublesome as one of those belonging to Oriel College, Oxford. You can see the statue in question in the alcove directly above the door in the postcard – the one on its own at the top; not one of those along the first floor. And I bet by now you’ve guessed the statue. It’s of Cecil Rhodes: plutocrat, imperialist and, crucially for this post, alumnus of, and donor to, Oriel College, Oxford.

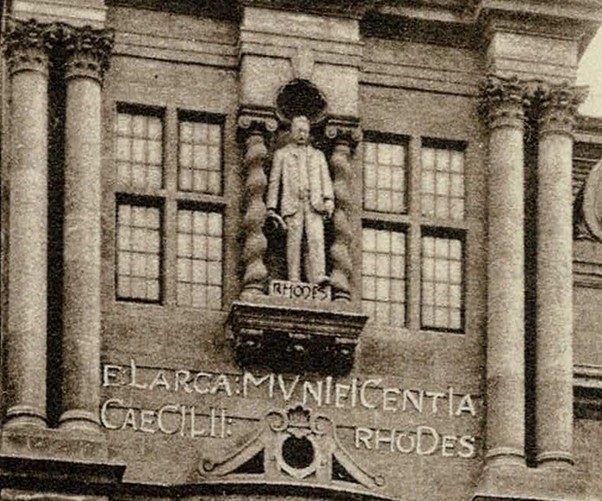

You can see the statue a little better in this close-up from anther postcard. The Latin reads something like “from the generosity of Cecil Rhodes.” (It is also, apparently, a chronogram – the outsize capitals giving the date of construction, 1911, in Roman numerals. And it does, if you ignore the order and just add up all of the Ls, Ms, Is, Cs, Ds and Vs. There’s a really good site here to help.)

Rhodes made money – a lot of it – from diamonds, and become politically powerful within the British southern African colonies. I’m not going to attempt a biography in this post; you can read here what Britannica has to say about him. He studied at Oxford between 1873 and 1881, the extended length of time not being explained by his gaining higher and higher degrees, but by his interrupting study to return regularly to South Africa.

Rhodes became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony (as it was then known), and played critical roles in the British wars against the Zulu and against the Boer (he fomented the incident which led to the war against the Transvaal). He was an ardent imperialist: writing about the English, he said:

I contend that we are the first race in the world, and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race. I contend that every acre added to our territory means the birth of more of the English race who otherwise would not be brought into existence.

Rhodes died young – aged 48 – and in his will left £100,000 to Oriel College (worth about £10.5 million today), a chunk of which was used for a new building on the High Street side of the college. Its the one in the postcard with the statutes. He also left money for other educational goals – for example, land in South Africa which became the campus for the University of Cape Town; and famously the Rhodes scholarships, which support students attending Oxford from the former British empire, and from Germany.

In 2015, students at the University of Cape Town protested against a statue of Rhodes on campus. As this piece makes clear, the statue was the symbol, the protests had a broader target: the legacies of colonialism and racism within and beyond the university environment. The university’s council agreed with the protestors, and the statue was removed. Students 1, Rhodes 0. And a slogan – #RhodesMustFall – gained currency.

In 2016, a focus of what had become a movement fell on Oxford. The Oxford Union debated and passed a motion in favour of the removal of the statue on Oriel college. In 2020 the matter surfaced again, with student protests in Oxford, and resolutions in favour of removing the statue from the undergraduate and postgraduate students of the college. Trickily for the college, the building – and hence the statues – were listed, so simply removing the statue was not possible. The college’s council agreed to hold an independent inquiry to make recommendations, and when the report was received in 2021, voted to seek to remove the statue. But, the environment was hostile, and it was clear that government, whose approval would be necessary, would not approve.

The college has published a good explainer, which includes links to pieces by Professor William Beinart, Emeritus Rhodes Professor of Race Relations, outlining Rhodes’s legacy; and by Professor Nigel Biggar, Emeritus Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology, arguing that Beinart’s criticisms of Rhodes were overplayed.

Now, the issue to me seems fairly simple. Did Rhodes’s actions lead to a state of affairs where if you have black or brown skin you were treated far worse than if you had white skin? The history of the twentieth century in southern Africa say clearly yes. Should we therefore be memorialising him? Reader, I invite you to answer this one for yourself.

And that is how things currently sit. Whether under a different government permission to remove the statue might be given I do not know. Sculptor Antony Gormley suggested that the statue be turned to face the wall in shame – maybe that would be permitted? I do suspect, though, that we haven’t yet heard the last of this one.

And here, as is customary, is a jigsaw of the postcard – enjoy!

“Did Rhodes’s actions lead to a state of affairs where if you have black or brown skin you were treated far worse than if you had white skin?”

One wonders why people get so upset about something that happened well over a hundred years ago in a land far-far-away when today in this country if you have white skin you are treated far worse than if you have black or brown skin? As one example a link to wonkhe’s favourite publication Spiked:

https://www.spiked-online.com/2025/04/03/labour-is-still-ushering-in-two-tier-justice/