Greetings from the past!

Today’s postcard (which, as we will see, was sent in 1907) is full of heraldic shields. And the shields are a colourful, if eclectic, selection.

You’ve got the four Scottish ancients: St Andrews, Glasgow, Aberdeen and Edinburgh. But not Strathclyde, which was known as Anderson’s University in the mid-nineteenth century.

You’ve got the Welsh university colleges (as they were then) at Aberystwyth, Bangor and Cardiff; but also St David’s College, which wasn’t part of the University of Wales; and the University of Wales itself is absent.

You’ve got the English universities – Oxford, Cambridge, Durham, London, Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds and Sheffield. And then you’ve got some institutions which were definitely not yet universities – Bristol (1909), Reading (1926), Nottingham (1948), and Southampton (1952).

In Ireland you’ve got Dublin (which is the university of which Trinity College Dublin is the only college); Queen’s Ireland (which did not exist in 1907, but the shield is similar to Queen’s Belfast); and Ireland, which is the Royal University of Ireland, which included Queen’s College Belfast, as well as counterparts at Dublin, Cork, Limerick, Galway, and Derry.

And then for the then colonies you have Sydney (1850) and Melbourne (1853), but Adelaide (1874) and Tasmania (1890) are ignored. Missing completely is the (then) University of Bombay (1857). Also absent: no end of universities in Canada, including (but not limited to) McGill, Dalhousie, Toronto, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Université Laval, Ottawa. Loads of Canadian universities. And not present either are the New Zealand/Aotearoa universities which existed in 1907: Otago, Canterbury, Auckland and the Victoria University of Wellington.

So, there’s a lesson here that you shouldn’t put too much weight on postcards as a reliable source of information (as we have also seen in the case of University College Oxford).

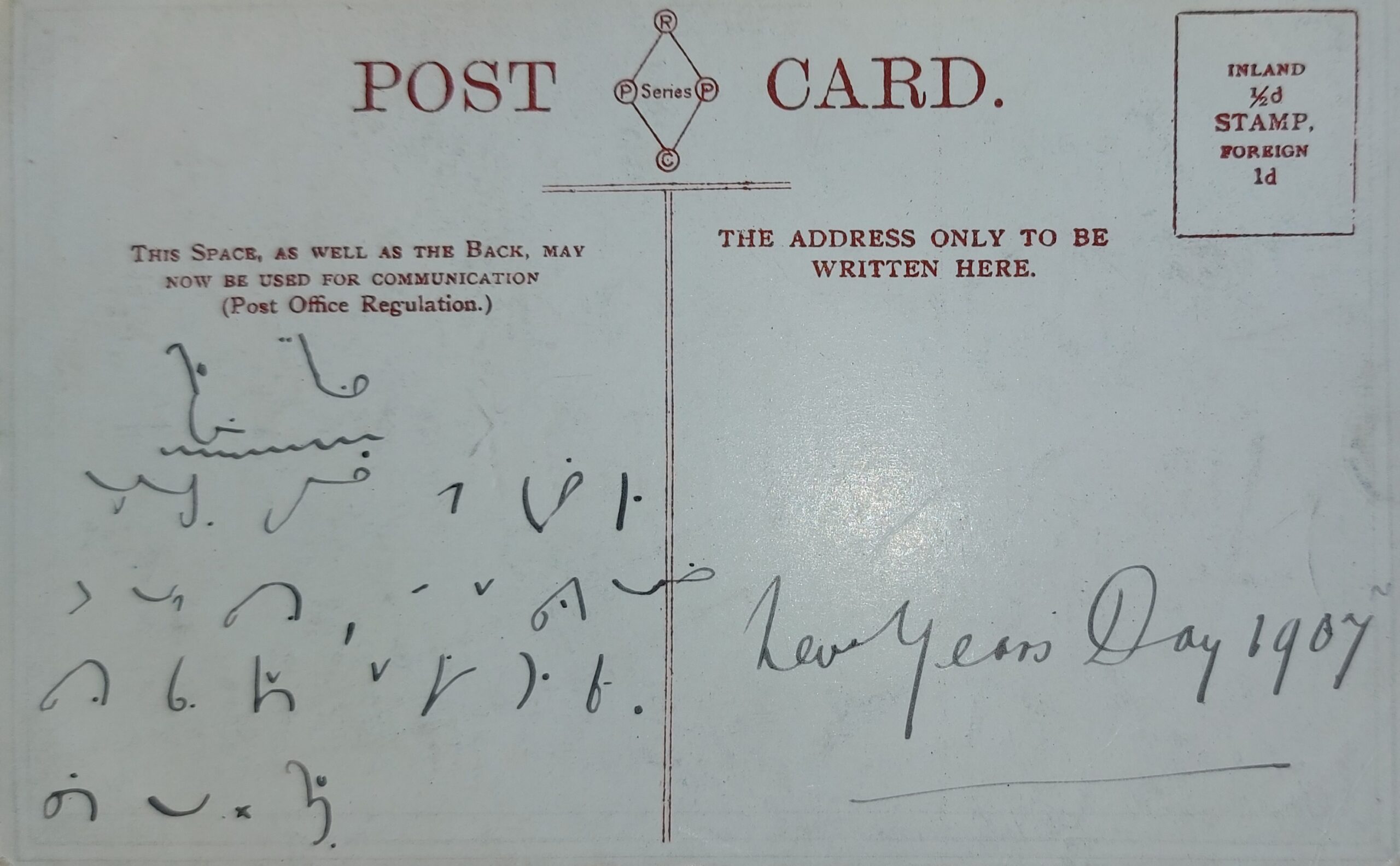

But the back of this card makes it special.

Dated New Year’s Day, 1907, there’s a message in Pitman shorthand. Which I can’t read. But thanks to the power of Twitter, and the kindness of Annie Rosina Compton (and friend) and Kathryn Baird (who has written a book on shorthand postcards!), I can share what the message says:

Perfect happiness. Nineteen weeks and the first day of the New Year and I hope this time next year I shall say just the same thing. Fraser

Who was Fraser, and to whom was the message addressed? We’ll never know. But its good to have a touch of mystery romance to wonder at.

It’s a fine postcard, nicely decoded by Hugh. As ever, it’s interesting to see how hierarchy is depicted by commercial interests (in this case to sell a postcard, see also league tables). If the postcard was printed in 1905 or 1906 (so after Sheffield gets university status) then they are looking forward, as Hugh notes, to Queens’ Belfast leaving the federal university in Ireland. It stops being the Royal University and becomes the National University in 1908. The dates given to the former members of the Victoria University are odd – both Manchester and Leeds have 1880, which is the… Read more »