Greetings from Kyiv, and a card from happier times.

In the late nineteenth century, sugar was a dominant industry around Kyiv, and the need and desire for technical education was clear. The idea of establishing a college was mooted, and in 1880 a fundraising campaign launched to help establish such a college. In November 1896 the Tsar’s Finance Minister, Sergei Witte (yes, that one), authorised the establishment of the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute.

Modelled on the polytechnics being established elsewhere in Europe (for example, the Polytechnic Institute Zurich, now ETH Zurich), the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute opened in 1898 with four departments: mechanics, engineering, agriculture, and chemistry. Entrance was by examination, and 1100 students were tested for 330 places. Following an appeal by the University’s Board, the Ministry of Finance agreed to fund an additional 30 places to help meet demand.

By 1902 the Institute’s building – the one shown on the card – was complete, and the Institute had a full suite of laboratories, libraries, refectories and so on. Kyiv had its Polytechnic Institute. As a new institute, there was an obvious need to ensure that standards were set high, and Dmitri Mendeleev – Professor at St Petersburg University and the inventor of the periodic table of elements – was the first chair of the Examination Board at the Institute. This does suggest a certain rigour.

The Institute was a pioneer in aviation in the Russian empire. In 1899 a club was formed, which by 1905 had become the aeronautics section of the Institute, with lectures and practical work, building and flying (in time) gliders and aeroplanes.

After the revolution of 1917, and the civil war, reconstruction was needed, and the Institute played its role, being designated in 1934 Kyiv Industrial Institute. By June 1941 the institute had 3000 students, and over 300 faculty members (out of a total staff of 5000 – a good datum for those who think today’s universities have too many non-academic staff!).

And then war came again to Kyiv. The Institute was evacuated to Tashkent, becoming for a while part of the Central Asian Industrial institute. But in late 1943 it was able to return to Kyiv, and in 1944 the academic year started afresh in Kyiv. The institute’s buildings had suffered in the fighting, and in summer 1945 students and staff worked over the summer to repair and rebuild the Institute (the Institute’s history calls this voluntary, but I’m not sure how much volunteering there really was in Stalin’s USSR …)

In 1948 it was renamed again – the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute Order of Lenin, and again in 1968 to the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute Order of Lenin of the 50th Anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution, which surely matches the formal names of some of the Oxford Colleges.

(Take, for example, “The College of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Saint John the Evangelist and the glorious Virgin Saint Radegund, near Cambridge”, or Jesus College Cambridge as you more likely know it.)

In 1989 a graphic arts faculty was established in the University, incorporating the Kyiv evening faculty of the Ukrainian Polygraphist Institute, named the Fedorov Institute for, I believe, nineteenth century philosopher Nikolai Fedorovich Fedorov.

This had been established in 1954 as the Art and Crafts School of Graphic Arts № 18, a department of the Moscow Printing institute.

(I give all of this detail not because I think that in itself it has long-term significance, but because I find it fascinating how different cultures recognise and share authority and quality. In UK higher education we do it with faux medieval architecture, in the Soviet Union they did it with institutional family trees.)

In 1995 the Institute was given the status of National Technical University, and it is today the largest higher education institute in Ukraine. You’ll not be surprised to know that it is no longer named after Lenin, but it does commemorate a famous alumnus- Igor Sikorsky, he of the helicopters.

Its Sunday best name since 1996 has been National Technical University of Ukraine “Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute”.

Another famous alumni was Sergei Korolev, the first chief designer of the Soviet Space programme, and involved in both the Sputnik satellite and the Vostok human flights, with Yuri Gagarin becoming the first man, and Valentina Tereshkova the first woman, in space, in 1961 and 1963 respectively.

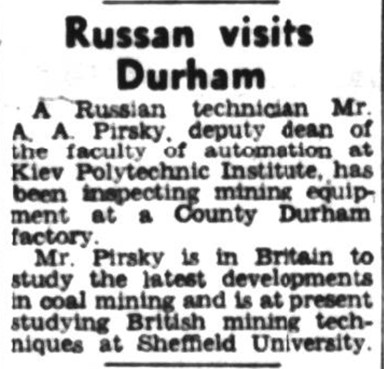

The Institute has left a small mark on the British press as well – here’s a report from the Newcastle Evening Chronicle of 10 March 1965. Almost certainly Mr Pirsky was Ukrainian not Russian, but such distinctions mattered less to us in 1965 than they seem to do today.