Three cheers for Emily Davies and Barbara Bodichon, nineteenth century pioneers of women’s rights in the UK, and founders of Girton College, Cambridge.

Davides and Bodichon founded Girton in 1869 as the College for Women. Initially based in a rented house in Hitchin (which is not in Cambridge by about 30 miles), the college moved to Cambridge in 1873, with buildings designed by Alfred Waterhouse (who also did the Manchester Town Hall and the Natural History Museum).

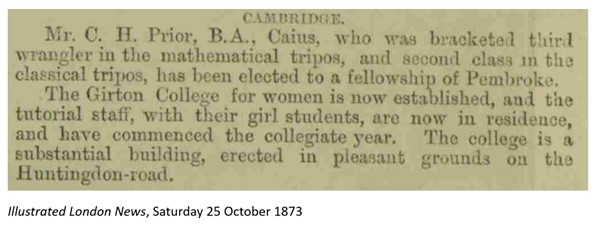

The Illustrated London News noticed the college’s move, reporting on it in October. It’s a college for women, but the students are girls …

Girton students could not at this point take Cambridge degrees or sit university examinations. The latter changed in 1880 following the performance of Girton mathematics students in examinations. In 1888 a Girton classicist outshone all others in exams, prompting a committee to be established to push for women to be able to graduate.

The events of 1897 enabled the success of this effort to be judged. The Daily News (London) of Saturday 22 May 1897 takes up the story:

WOMEN DEGREES AT CAMBRIDGE. A HOSTILE VOTE. LIVELY PROCEEDINGS. Our Cambridge Correspondent telegraphs:

“The question whether women should receive titular degrees at the hands of Cambridge University has been decisively answered. The voting took place at the Senate House yesterday, before the Vice-Chancellor, between the hours of twelve and three, and very soon after the poll opened it was apparent that the non-placets, or those voting against the Grace that women should receive degrees, were in a large majority. During the time prescribed for voting there was a large stream of voters, and many were those who exercised the franchise who had not been to the Senate House for years. The scene outside the House was almost an indescribable one. On the lawn in the Senate House yard Were assembled those who had recorded their votes, and on the other side of the railings in the public road there were hundreds of undergraduates; who amused themselves in various ways until the declaration took place. Fireworks were plentiful, and placards of all descriptions were exhibited against the case of the women.

Punctually at three o’clock the voting was announced as follows: Non-Placets 1,713 Placets 662.

This voting was on the first Grace, which involved the principle. The other Graces affecting the details were withdrawn. The terms of this first Grace were as follows: “That it is desirable that the title of Degree of Bachelor of Arts be conferred by diploma upon women who in accordance with the now existing ordinances shall hereafter satisfy the examiners in a Final Tripos Examination and, shall have kept by residence nine terms at least, provided that the title so conferred shall not involve membership of the University.”

Another Correspondent says: “The result was received with deafening cheers, the majority against the scheme being larger than was anticipated. The figures were placed on a board and carried through the principal streets by the President of the University Boat Club and another Blue. Later, the triumphant undergraduates marched to Newnham College loudly cheering. There was no disturbance, but a few windows in some houses were broken by oranges and other missiles thrown by the collegians. Those indoors derived great amusement from distributing liberal supplies of confetti, flour, rice, and water upon those assembled outside. In the evening the undergraduates were exceedingly lively, and Market-hill was the scene of an animated demonstration. A bonfire was lit, and there was a display of fireworks on a grand scale. Good humour, however, prevailed, and as the crowd was apparently of one mind there was not likely to be any mischievous results.”

Despite this setback the college continued to grow, expanding its buildings and increasing the number of students who could be accommodated. The new buildings included an indoor swimming pool (always an expensive venture!) and one of the largest dining halls in the university.

In 1924 the college gained a Royal Charter. It was growing in prestige and status, but was still not a full college of the university: it was simply a “recognised institution for higher education for women.” In 1947 the University of Cambridge finally decided to admit women to university degrees, and in 1948 degrees were awarded to Girton women for the first time. The college was also at this point admitted as a full college of the university, 79 years after its foundation.

(For perspective, note that it was not until 1956 that women and men were permitted to sit examinations in the same room at Cambridge.)

Girton had been for women only since its establishment, but in 1971 it amended its statutes to enable the admission of men to be contemplated, and in 1976 actually decided to admit men. First in 1977 to fellowships, then in 1978 to postgraduate degrees, and then in 1979 to undergraduate study.

Girton has had its share of illustrious alumna, including Delia Derbyshire, pioneer of electronic music and arranger of the Dr Who theme; Baroness Hale, President of the British Supreme Court; and Dame Rosalyn Higgins, former president of the International Court of Justice.

The card is unposted, but is part of a series published by the Great Eastern Railway in 1905 (the GER ran trains out of Liverpool Street – it looks like they were promoting the idea of day trips to Cambridge).

The college has a really good webpage outlining its history, on some of which I have drawn in writing this blog.