By special request of my friend Jenny Jenkin, we’re going back to Exeter. And, because it is 18 October, which is St Luke’s day, we’ll look at the teacher training college which became the St Luke’s campus at the University of Exeter.

We need to start with a brief overview of education in England in the nineteenth century. And I’m talking school education here, not higher education. There were ancient private foundations (think Eton, Harrow, Westminster, Winchester and the like) which provided for the sons of the ruling classes. And, later in that century, a smaller number of establishments for their daughters (for example, Cheltenham Ladies College). There were charitable grammar schools – fee paying – which provided for the sons of the wealthier middle classes. And there were Sunday schools which – in 1831 – provided some limited education for 1.25 million children, which is about half the number there were. (If you want a fantastic timeline of developments in education in the UK, try this one!)

In essence, education was considered a private concern. Which led, obviously, to a population which was less educated than neighbouring countries which had approached things more top-down. And aside from the moral arguments, industry suffered through a less educated workforce. In 1839 the first vestiges of consistent state intervention took place, with the creation of a Committee of the Privy Council on Education, to decide how to spend any money that parliament voted for schools. And there was money, given to two educational charities – the National Society and the British and Foreign School Society – and for building schools.

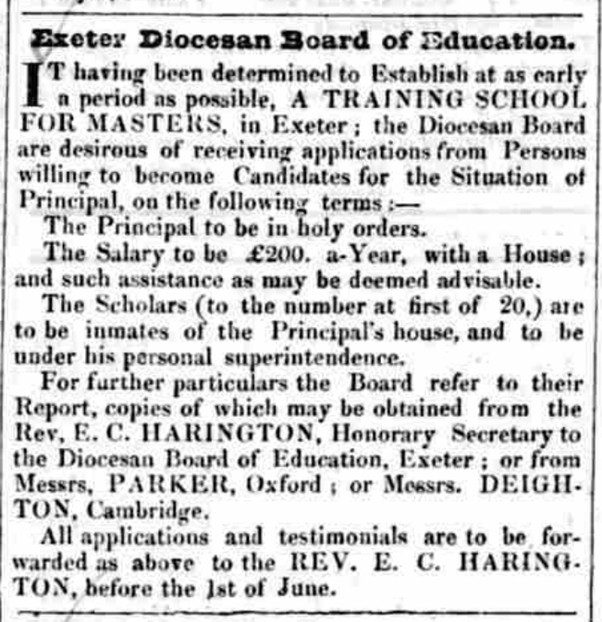

But who would teach the children in these schools? This is where the church stepped in: some dioceses established boards of education, which in turn established training colleges, so that school teachers could be educated. Which story was the case in Exeter. A training college was to be established, and in May 1839 advertisements (see, for example, from the Royal Cornwall Gazette on 3 May 1839) were run seeking a principal for the training college:

(I’m struck, by the way, as to the efficiency of the advert: the key requirements clearly stated, a straightforward process, a reasonable timescale laid out. And, by the look of it, the use of executive search, by way of Messrs Parker and Deighton …)

The first students were taught in a house in the cathedral close in Exeter, where it clearly thrived. In 1853 purpose-built accommodation was commissioned, which opened on 18 October 1854: the Exeter Diocesan Training College was founded, and today (18 October 2024, when this piece is schedule to be published) is the 170th anniversary of the new college opening. Happy anniversary!

The college continued to grow, with new and expanded buildings: a chapel in 1863; further new buildings in 1911-12, 1934 and 1938. And then in 1942, Exeter suffered heavy bombing during World War 2 (part of the so called Baedeker raids), and several of the college’s buildings were severely damaged, including the chapel, which was totally gutted by fire. Repairs were not started until 1950, and not completed until 1952.

By this time the college had a new name: St Luke’s Training College. Women were admitted as students in 1966, and further buildings (a refectory and more residences) were added in 1967.

By this time, as regular readers of my blogs will know, the tide was turning against smaller colleges. Teacher training colleges, art schools, technical colleges and colleges of commerce were all being merged to form larger colleges, and sometimes polytechnics. In St Luke’s case, the college merged with the University of Exeter, becoming part of the school of education in 1978. And the St Luke’s campus is now one of three campuses of that institution.

There’s a very good but brief history of St Luke’s which I’ve drawn on in writing this narrative – it’s well worth a look.

Now for some St Luke’s snippets.

Firstly, the very fine photo history of St Luke’s, which was written clearly in sorrow and regret at the college’s demise in 1978, shares an image of the 1909-10 hockey team, with a frame calling the college St Luke’s University College. This derived from its brief association with the University of Oxford – an affiliation which mean that students who had completed study at St Luke’s could gain direct entry to the second year of studies at Oxford.

Secondly, a St Luke’s character – Stanley Rous (later Sir Stanley Rous) studied at St Luke’s. He went on to be a notable football referee, the secretary of the FA from 1934-1962, president of FIFA from 1961-1974, and innovator – red and yellow cards and a new system of running for referees (the diagonal system, which makes sense if ever you’ve read the wonderfully titled Referees’ Chart and Players’ Guide to the Laws of Association Football, which is the official rule book.)

Thirdly, a St Luke’s founder: Charlotte Hippisley-Tuckfield, educationalist, advocate for sign language, and also the founder of the first school for deaf children. You can read about her significant role in the education of deaf people here.

The card itself was sent on 12 September 1905, to a Mrs Wyllie in Paisley.

I will have heaps to tell you when I get home. This is a most interesting old town and I have been to some of the coasting places near. Annie

One of my team took Chemistry at Exeter, before they shut the dept.

Interestingly a team of technicians from Southampton’s Physics dept workshop spent many months refitting labs in Exeter, having undercut the costings by the local techs, many of whom were made redundant shortly after. And as a result the Physics workshop in Southampton didn’t do ANY work for their own University for that time, the money they brought in, and the overtime and travel expenses they claimed made it all worthwhile I’m told. I wonder if they still do such jobs?

Hi Hugh, fascinating as ever, thank you. You are right that the churches got involved in setting up teacher training colleges (Anglican, Catholic and Nonconformist.) The National Society and British Society you refer to were Anglican and Nonconformist respectively, and the Catholic church also set up lots of elementary schools. It was not until after 1870 that the state provided for the establishment of secular schools where there was no faith-based provision. There are, of course lots of C of E primary schools and Catholic still, the nonconformist churches changed their approach later in the century and campaigned for secular… Read more »