My twenty years working in the field of data and insight has shown me its power in shaping a customer-focused culture.

My experience helping Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) to develop its market segmentation of taxpayers showed that moving away from business objectives that focus exclusively on taxpayer compliance to include customer experience in performance measures is hard for those habituated to working in a particular way.

While there was a greater moral obligation to treat taxpayers as customers, many officials struggled to stop thinking of tax dodgers as anything but criminals. Needless to say, some at HMRC saw customer segmentation as an expensive diversion, that is until experimentation showed it could be a cost-effective way to target scarce resources.

The customer segmentation of taxpayers shows how evidence-driven business strategy can be implemented to treat customer segments differently according to their needs, saving both HMRC and its customers’ money.

At that time, Fortune 500 companies were also aligning their efforts around customer segments, improving customer satisfaction with some successful field studies also reporting better performance (e.g. IBM, Intel, Fidelity Investments).

In many ways, HE is still adapting to what many other sectors did a decade ago. Learning from successful customer-centric models suggests the HE sector could also benefit from applying a strategic focus on students.

Segmented approaches

Segmentation is not the same as sub-group analysis. We often see HE institutions conducting sub-group analysis using socio-demographic indicators (ethnicity, POLAR, working status, and so on) to find statistical differences in academic performance or student experience.

Students have a wide range of attitudes, motivations, behaviours, and expectations that can be organised around needs rather than characteristics and together can help universities to better understand young people’s experiences and struggles. When combined effectively, these can override the influence of socio-demographics and offer more actionable insight.

Insight for Good is a social enterprise I run that helps organisations achieve their social and organisational goals. As part of our research agenda, we were inspired to investigate the social aspects of the skills gap in a generation who wanted to change the world but were also three times more likely to be out of work or underemployed. Throughout our research, it became clear that students had been left out of the conversations between employers and universities about getting young people into graduate-level work.

Looking to offer a new perspective on the problem, we conducted secondary, qualitative and quantitative research in order to understand students’ attitudes, needs and behaviours, and to help employers and universities engage with them more effectively. In particular, the quantitative study consisted of an online survey with a nationally representative sample of university students in the UK (n=496).

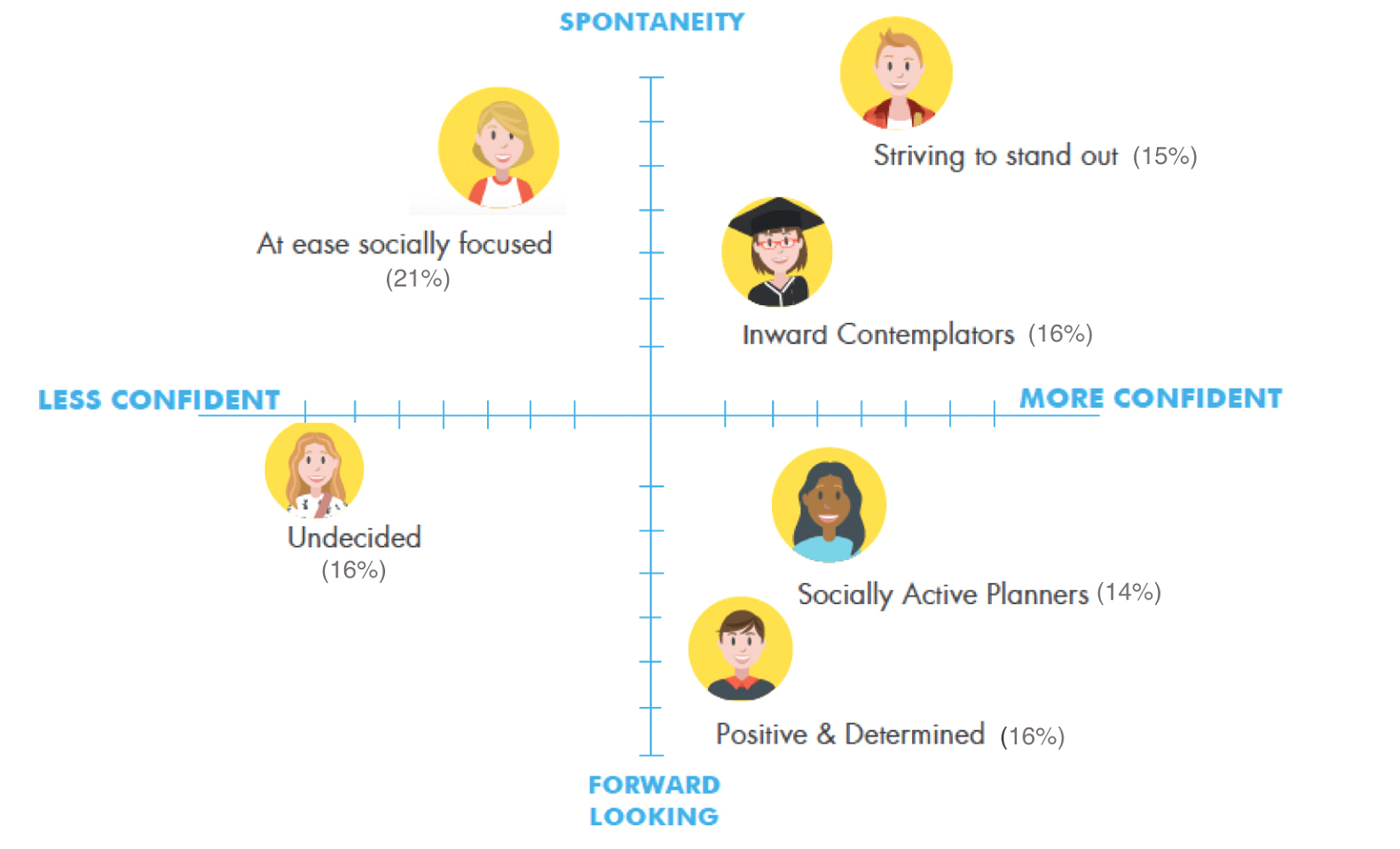

We asked students to respond to wide-ranging questions around their background, university and career choices, health and emotional stability, social behaviours (including face-to-to face and online), leadership aspirations, confidence levels, engagement with their university, as well as questions to understand their work readiness, social conscience, and future plans and expectations. Injecting statistical rigour through factor and cluster analysis, the output was a segmentation made up of six groups:

Example UK university students segmentation

Source: Market Segmentation: Avoiding a one size fits all education, Insight for Good

This contrasts with subgroup analysis that uses only one characteristic to understand internal data or survey responses. While the former can highlight interesting differences across subgroups, it has an inherent bias towards such differences, whereas other variables, when combined, prove more insightful for explaining the complexities of human behaviour.

For example, in our segmentation, the analysis helped us identify that two factors (the ability to forward plan and having inner confidence) helped differentiate the segments. These insights led us to review academic research to discover how these two factors are also critical to academic achievement, helping pinpoint why the segments in the right-bottom quadrant (what we call “socially active planners” and “positive and determined”) had the best academic results and interestingly, from a socio-demographic point of view, the highest parental income.

Strategic segmentation could help universities to more confidently develop their service offerings and prioritise service improvements, as in this illustrative example:

Student-centric strategies

Source: Market Segmentation: Avoiding a one size fits all education, Insight for Good

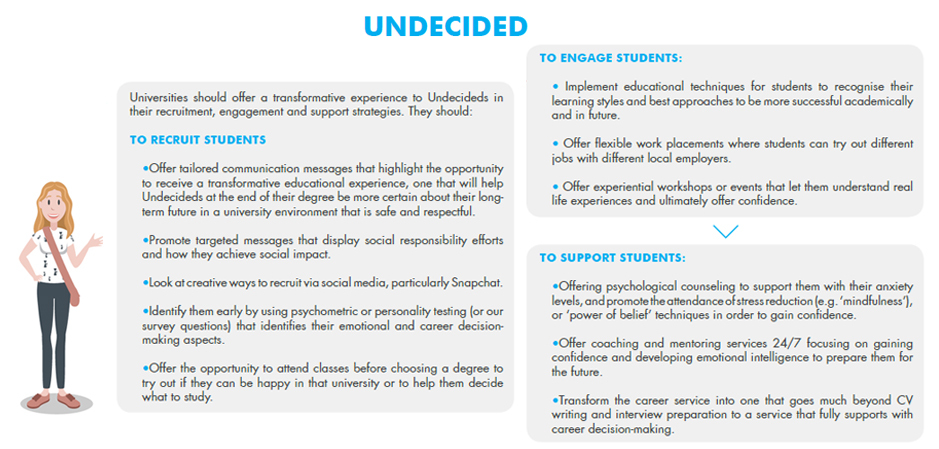

Such strategic planning can be done at a segment level once universities have detailed segment insights that can be looked at as a whole, helping to develop recruitment, engagement and support strategies that meet business objectives such as enhancing the student experience, employability and retention. Below is an illustrative targeted approach for one of the six segments that a university may wish to consider:

An example of how to treat a student segment

Source: Market Segmentation: Avoiding a one size fits all education, Insight for Good

The value of segmentation

A segmentation approach is even more valuable when universities can compare their own segment composition against the full student market and see where they have gaps. This can help to identify certain segments to target through tailored and more engaging messages, in turn, driving marketing effectiveness.

And segmentation can also help inform how to improve the student experience. Presenting experience scores by segment will help universities understand which services are underperforming for which groups and why. At HMRC, it helped to bring staff together, sharing a common language across functions and getting staff more engaged in the customer. University departments, from marketing to employability and service delivery, could more effectively work together if used a student-centric language that everyone understood.

Not just sophisticated analytics

Delivering HE is becoming a consumer-focused proposition – it is no longer enough to see education in terms of delivery. Advances in technology and data such as learning analytics should not displace the strategic importance of holistic insight into students, their hopes, aspirations and struggles.

Learning analytics may help develop personalised learning segments based on the interactions and learning trajectories of students through traceable interactions, such as virtual learning environments, classroom attendance, or library visits. They can be powerful for identifying at-risk students and providing personalised learning recommendations.

But the data collection from learning analytics systems is predetermined from the outset by the software that collects the data, which may or may not have been designed with a strategic educational outcome in mind. For instance, analysing the data obtained from the aforementioned interactions will not address important issues such as the mental health of students.

Unless universities work backwards from the outcome they desire can they start understanding the behaviours that make a real difference to learning and the overall student experience.

These insights can then be addressed via learning analytics. Only when we stop treating students as data points and start humanising the insights obtained from the research will the HE sector be more effective at improving the student experience.

Personalised services

With their rising expectations of personalisation and immediate gratification, young people want service offerings to adapt to them. But a strategic segmentation can still help deliver services that feel personalised without necessarily needing to treat each individual student differently.

From our research, the “positive and determined” segment (who are career-driven but have little interest in getting work experience during their studies because of their optimism bias) can be encouraged to attend leadership workshops in which alumni talk about the value of work experience. They can also be offered flexible study options to encourage them to combine work and study time.

By contrast, “undecided” students (who tend to suffer from anxiety and be unclear about their choices) can be offered a set of services to help them see their time at university as a transformative experience. They can be approached with tailored messages to help them understand their options and get mental health support that helps reduce anxiety.

Designing a service offer that responds to students’ real needs will help them be more engaged and increase the take-up of services — enhancing the overall student experience and employability, and helping universities to achieve their objectives.