‘You’ll find it’s doing you an awful lot of good, that medicine… George said.’

After all of the excitement of Jo Johnson’s first speech, the TEF and HEFCE’s continuing thoughts about quality, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the policy agenda for HE under the new Conservative government is beginning to take shape. But these are all measures that look to manage the longer term health of the sector and there are more immediate issues to think about.

So before we all coast off into the summer holidays, there’s the small matter of this year’s second Budget to contend with. It’s the first all Conservative Budget since 1997 and the first real opportunity to see how George Osborne intends to use his party’s parliamentary majority. It will also be his first Budget as First Secretary of State (and the first person since Lord Mandelson to hold that office). He’s de facto Deputy Prime Minister, as well as lead strategist and policymaker in this Conservative majority government.

He is also the dominant thinker in this government and increasingly the most likely beneficiary in its wars of succession. He has many more supporters around him than before – Sajid Javid, Amber Rudd, Nicky Morgan and Greg Clark have all held junior HMT positions under Osborne. Jo Johnson is reportedly a fan as well, and they certainly worked together closely when producing the Conservative manifesto. On the plus side he’s stronger than Theresa May who he now outranks and outguns in political support. His are the arguments on growth that need to be deployed if universities are to take on Theresa May’s immigration rules and targets.

Almost every Conservative ambition in the next five years rests on George Osborne delivering economic growth and improved productivity. It’s the cure for all ills. That is his immediate mission and if he delivers it then his chances of winning both the leadership and the 2020 General Election increase significantly. He’s already mapped out his intentions in the recent Mansion House speech:

“Britain must address its poor productivity. We don’t export enough; we don’t train enough; we don’t save enough; we don’t invest enough; we don’t manufacture enough; we certainly don’t build enough, and far too much of the economic activity in our nation is concentrated here in the centre of London. We will tackle each and every one of these weaknesses with the same determination we have brought to tackling the deficit – and we’ll draw the whole government effort together in a single plan for productivity next month.”

Jim O’Neill is Osborne’s man leading the agenda. O’Neill has been thinking about reviving Northern cities as well as developing new anti-microbial medicines. He believes the former is a bigger ask than the latter. And Osborne’s big challenge is to address these issues while simultaneously cutting government expenditure more deeply and more rapidly than in the last Parliament. BIS is unprotected and according to the IFS could face reductions in the region of 30%. So that’s one reason why Johnson hasn’t yet found room to link the proposed TEF to funding outcomes or incentives.

There are manifesto commitments to fulfil such as more Catapult Centres and University Enterprise Zones. So too, 3 million apprenticeships – with degree apprenticeships and 2 year degrees somewhere in the mix. And of course there’s the Northern Powerhouse – as tied to Osborne’s legacy as the Big Society will be to Cameron’s. Both feature heavily in the manifesto.

But many of the headline sector issues such as the TEF, the quality assurance system and even the campaign to increase £9k fees in line with inflation, offer little to the Treasury in terms of any immediate economic effect. They might over the longer term, but none are productivity or growth-enhancing measures for the next few years, and that’s what Osborne and the Treasury want most of all. So all of these issues can wait. Some perhaps until the final year of this parliament when there looks to be more financial flexibility.

So this will be a Budget that shifts focus from the general and the long term to the specific and the shorter term. From the macro long term commitments for more graduates and more science to micro level initiatives that deliver more jobs and more growth. That isn’t an entirely comfortable place for HE but it’s a bargain that universities may well have to make if they want to retain income levels.

That’s because it’s going to be very, very tight. The £450m in-year cuts for BIS are already landing. The suggestion is that at least £150m of that will come from HEFCE. That will mean less opportunity to smooth out reductions in funding elsewhere and more pressure on sector bodies, on student opportunity and on other teaching funds but the real action will wait for the Spending Review. So the much-discussed grants to loans switch, the research ring-fence and other substantial pots will come under pressure next year.

The Treasury always engage in clawing back underspends and in recycling spending from low priority to high priority schemes. So we’ll see at least some of the £450m coming back to the sector but via headline-grabbing and job-creating or productivity stimulating measures. More rounds of RPIF, more HEIF or Catalyst funds? There may be some measures on postgraduate loans following recent announcements and consultations but I’m betting that most of George’s medicine will focus on shorter term, specific projects or competitive programmes that offer opportunities for joint investment and immediate return. I’m guessing that is how much of the next few years and the next few Budgets is going to feel.

As David Russell – chief executive of the Education and Training Foundation and a former government colleague recently pointed out, the Treasury and government more broadly, tend to ask the following questions about policy: Firstly does it matter? Does it help to deliver the manifesto? Secondly, do voters think it matters? Is there political advantage or opportunity in it? Thirdly, will someone else pay for it? Does government have to fund all of it? Finally, and most significantly, will money spent here be more effective at meeting priorities than money spent elsewhere?

It’s that last one that allows the short term to trump the long term and the specific to be prioritised ahead of more general activity. It’s the age-old Treasury question: if we have extra money what do we get most value for? That’s always difficult for universities or colleges as well as others to fully grasp. Of course both are important but at a time of scarce resource, are they as important as other things?

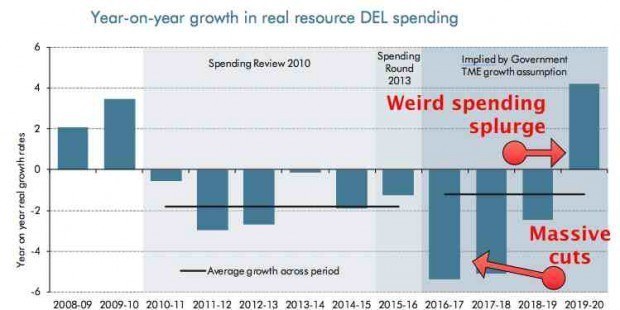

This is made even more challenging when we look at the current spending profile expected in this Parliament. The chart below from the OBR (with some added explanation) from this year’s first Budget shows just how deeply Osborne is going to have to cut in the first few years. And this is before he can find new money for productivity or growth enhancing announcements. Fraser Nelson, the editor of The Spectator, pointed out that the first few years of deep cuts, clearly much deeper than under the Coalition, look odd when the ‘spending splurge’ at the end of the Parliament is also factored in.

Osborne might choose to make these cuts a little more smoothly and over a longer period, even if that does run contrary to his pre-election promises. But for now this is what’s on the table. He’ll be hoping that his medicine will deliver an economic miracle. Cuts at a frightening scale, a shrinking state but lifting productivity and boosting growth at the same time. It’s the traditional Conservative ideology after all.

But it’s also a cure that may be keeping Osborne awake at night as well as a few vice chancellors and principals. This is medicine that will have an awful lot of things in it. As with Roald Dahl’s George making magic medicine for his Grandma, it might be ‘so strong and so fierce and so fantastic it will either cure her completely or blow off the top of her head.’