I have been championing progressive family leave policies to progress gender equity for several years now; indeed, it is the focus of my PhD research.

Yet I am often left wondering why organisations in the sector seem more comfortable championing women in leadership programmes than developing appropriate family leave policies.

There is an incongruence between calls for gender equity and family leave policy and practice.

So why focus on transition to parenthood?

The gender pay gap, the average pay difference between men and women, provides an overall snapshot of gender inequality within a specific setting – be it an organisation, sector or country. The gender pay gap in the UK HE sector is 13.7 per cent, as at 2022.

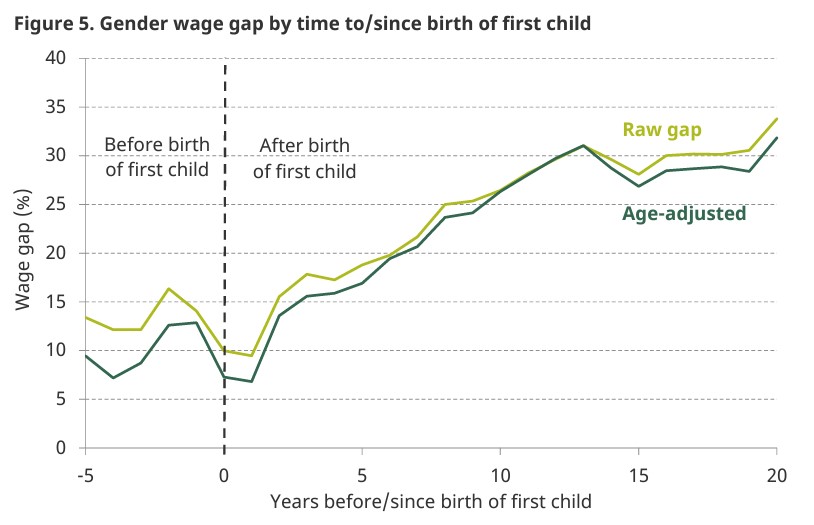

Transition to parenthood, and beyond, is known to be inextricably linked to the gender pay gap. As the work of Claudia Goldin, 2023 Laureate in the Economic Sciences, has shown the bulk of earnings difference between men and women arises after the birth of the first child. The UK gender wage gap in relation to transition to parenthood is illustrated in the following chart.

Intersection with other factors, such as contractual status, is also important. Within academia approximately 35 per cent of academic staff were on fixed term contracts in 2021, higher for early career researchers. Precarity increases unpredictability and difficulties in planning a family. Given eligibility to paid leave entitlements are normally based on continuous employment with one employer, having to move from one precarious contract to another increases the risk of only being entitled to the very basic maternity allowance. So, this, and the implied impact on staff wellbeing, might be a further driver to focus on family leave.

The recently transformed Athena Swan charter principles, which call for greater recognition and response to the gendered impact of caring responsibilities, may potentially be a further driver. And of course, there is the business case alignment between inclusive parental leave and employee recruitment, wellbeing and retention benefits.

Yet when we look at employer strategies aimed at tackling the gender pay gap and gender inequities, we see a predominant focus on recruitment, management and leadership initiatives; such as the HE Aurora women in leadership programme.

Of course, employers have family leave policies, but the question is, are these policies strategically driven to help tackle the gender pay gap and to progress gender equity? Is improving wellbeing and retention of staff a factor? Or is legal compliance the main driver? For example, the UK’s Shared Parental Leave (SPL) policy, introduced in 2015, has been recommended as a strategy to tackle the gender pay gap, yet few employers (including HEIs) have considered SPL in a meaningful way.

Leave entitlements

As has been well-documented, the UK statutory maternity leave offering, while one of the longest, comes with a miserly payment. Beyond the first six weeks, payment equates to less than 50 per cent of the national living wage. Paternity or partner leave remains only two weeks per year, with a similar miserly payment. As for SPL, low take up has commonly been attributed to policy flaws, such as low statutory payment and restrictive eligibility criteria.

The recent Government evaluation of SPL did nothing to address poor statutory provision. As a result, there has been criticism of government in-action and calls for a more equitable system for leave while still recognising the physiological demands of pregnancy and breastfeeding on mothers. In the context of poor statutory provision, employers are key – both to enhance statutory entitlements but also for creating organisational cultures in which parents feel able to access those entitlements.

UK employer enhancement of leave varies considerably. The 2023 UK benchmarking report found that 72 per cent of (responding) employers enhance maternity leave and 64 percent enhance paternity leave. This compared to 43 per cent of employers enhancing SPL pay, a rise from 25 per cent in 2017.

On first view

Back in 2016, approximately 94 per cent of HEIs enhanced their maternity leave, approximately 80% enhanced paternity leave and approximately 60 per cent of HEIs’ enhanced their SPL to match their occupational maternity leave pay entitlement.

A more recent comprehensive benchmarking across the HE sector has not been undertaken. However, responses to a recent Freedom of Information request show little change since 2016, although considerable variability in policy provision is evident. Enhanced maternity leave (and shared parental where matched) ranges from zero (i.e., statutory leave only for a remaining handful of institutions) to 26 weeks, an average of 18 weeks. A little over 60% of HEIs now match SPL and maternity leave entitlements and most institutions now enhance paternity / partner leave. Yet enhanced paternity / partner leave remains on average two weeks.

A growing number of universities, approximately 20, have removed eligibility criteria to leave entitlement to maternity, shared and paternity or partner leave and now offer paid leave as a day one entitlement – examples include Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Newcastle, Oxford, Cambridge, UCL, Edinburgh and Exeter.

In 2022, the University of the Arts London became the first UK university to offer equalised parental leave.

So, there are some positive signs, right? Relatively speaking, and assuming you work in one of the more progressive institutions in terms of family leave policy.

Workplace culture

The Government’s recent SPL evaluation showed that only 42 per cent of fathers and 51 per cent of mothers even knew about their potential SPL entitlement at the time of their child’s birth or adoption. Of parents who did not take SPL, approximately 40 per cent of parents reported discomfort with asking their employer about taking SPL. This discomfort is telling of workplace culture.

Within HE, only approximately 50 per cent of institutions have their family leave policies accessible on their website. Some 30 per cent of HEIs have not reviewed their policies in the last three years and several institutions still refer to the now obsolete Additional Paternity Leave, superseded by SPL in 2015.

But it is the language used that is most revealing. There are few examples of the notoriously complex SPL policy having been made more accessible. One HEI policy even refers to disciplinary action for potential fraudulent claims within its SPL policy. Lack of proactive implementation of family leave policies and resistance to more progressive policy change perhaps reflects normative assumptions about whether parents do want to share care or not.

Within my research, which focuses on SPL, participants suggested that simply having a policy is not enough. A fundamental message from parents was that making a policy available yet not proactively promoting it does not engender a sense of entitlement to access the policy. Parents’ calls for employers to go beyond simply making policy available, by bringing it to life through case studies and events, starkly contrasted the prejudice parents often experienced in practice. Currently, rather than enabling parents to share care, we are expecting them to share the risks associated with taking leave.

So, returning to alignment between family friendly policy and practice with EDI strategy, do variable approaches to policy and practice reflect variable overarching EDI strategic approaches? Or is there incongruence between EDI strategy and employer practice?

Within HEI EDI strategies, while reducing the gender pay gaps is often referenced as an objective or key performance indicator, the link between family friendly policy and actions to address the gender pay gap is less common. Furthermore, rarely is family leave policy explicitly aligned to the growing call for gender equity and what this means in practice.

Yet, is it a coincidence that UAL, which has a 3 per cent gender pay gap (reported in 2023) significantly lower than the sector, is leading the way on family leave policy?

Parental leave, in particular for the birthing parent, should at least match the organisation’s sickness leave pay policy. At the institution I work at the birthing parent could have any other operation and be granted 6 months full pay, 6 months half pay once they have 3 years service under their belt. But a c-section, followed by recovery and the hormonal upheaval that is the post-partum experience? Only 6 weeks full pay and 18 week half pay.