Parliament will soon return to the question of a statutory duty of care in higher education, because the first debate did not deliver the clarity or action that was needed.

The Post-16 education and skills white paper flags the issue – noting that a new Higher Education Student Support Champion will work to address the recommendations from the National Review into Higher Education Student Suicides.

More than three university students in England and Wales die by suicide every week. The duty to protect students from reasonably foreseeable harm is long overdue. Voluntary measures and optional good practice are no substitute for a clear legal duty.

The first parliamentary debate on this issue, held in 2023, left a crucial question unanswered – what does “duty of care” actually mean, and why do so many people believe universities already have one?

Every conversation about “duty of care” in higher education eventually runs into confusion. Some say universities already have one. Others insist they don’t. Both sound right – and both can’t be wrong. The problem is that “duty of care” means very different things depending on who’s speaking.

For families, it’s a promise of protection. For universities, it’s a matter of professional judgment. For lawyers, it’s a term of art – a legal threshold that decides whether the law even applies when harm occurs. But there’s a simple way to make sense of it – by borrowing a shape from soil science.

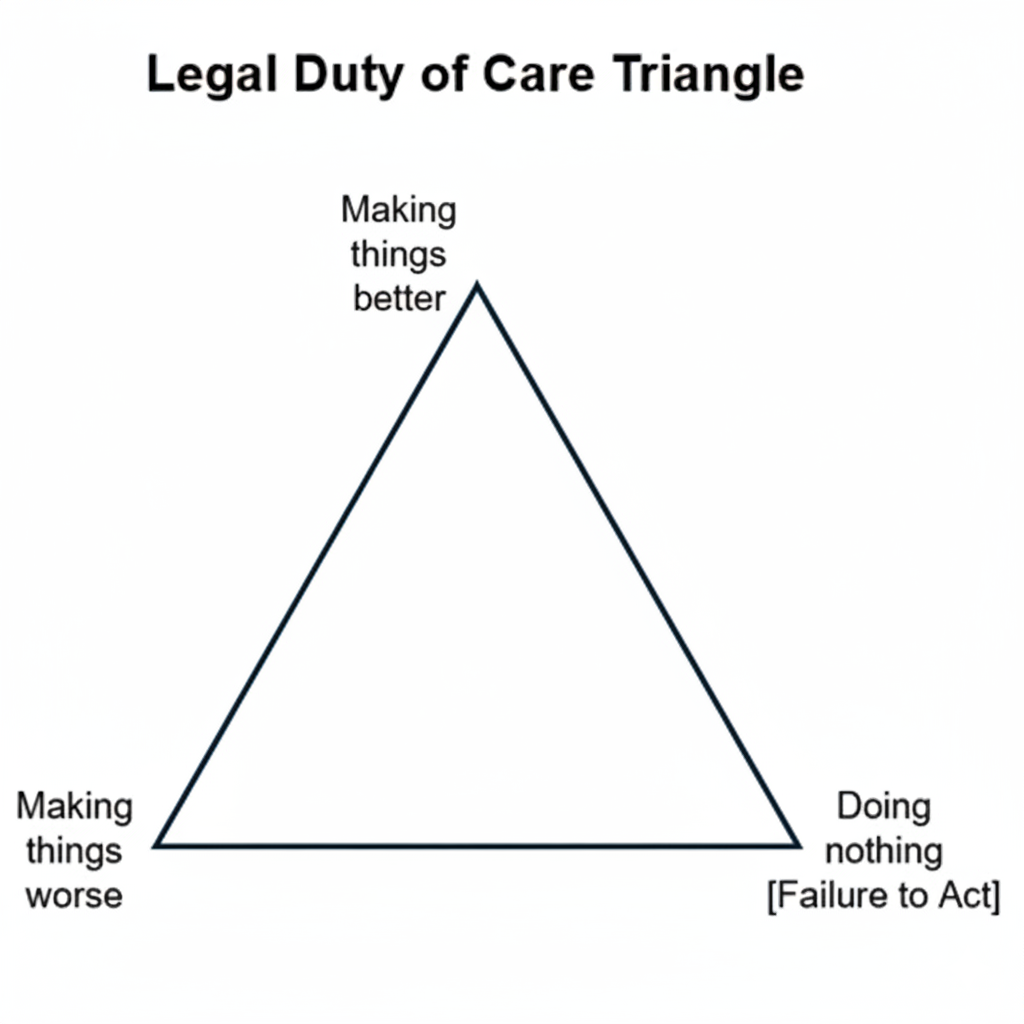

So as MPs prepare to revisit the issue, here I’ve set out a way to understand the debate in visual form – through what I’ve called the Legal Duty of Care Triangle. It shows, at a glance, why legal definitions, government policy, and public expectation have drifted so far apart – and why that gap matters now more than ever.

The concept

A ternary diagram is a triangular graph used to represent systems with three components that sum to a constant, typically 100 per cent. While traditionally employed in the physical sciences – in chemistry, geology or soil classification – to show compositional data, it can also be a powerful conceptual model for non-scientific problems.

By using the three corners of a triangle to represent three competing factors, we can visualise the balance between them and the resulting outcome.

The same idea can explain the legal concept of duty of care. Imagine a triangle whose corners are labelled “making things worse,” “doing nothing,” and “making things better.” Every decision, omission or intervention made by an institution can be plotted somewhere within that space. The position tells you what kind of care – or lack of care – is at play, and whether the law of negligence currently recognises it.

Acts, omissions and the Tindall judgment

The distinction between acts and omissions runs through English law. Courts are willing to impose liability for acts that cause harm, but rarely for failures to act, even when the need for intervention was obvious.

The Supreme Court reaffirmed this in Tindall v Chief Constable of Thames Valley Police [2024] UKSC 44, describing the difference between “making things worse” and “failing to make things better.” The law punishes the first but usually overlooks the second, unless a “special relationship” creates a specific obligation to act.

That single distinction explains why so many student cases – including Abrahart v University of Bristol (Court of Appeal, 2024) – fail to establish a general duty of care. The courts accept that mistakes were made, and even that harm was foreseeable, but can decline to impose liability by characterising the university’s failings as “pure omissions”, not actions that “made things worse.”

In the conceptual model, the three corners of the triangle represent three strategic approaches an institution might take when faced with foreseeable risk:

- Making things better – Proactive action. Taking reasonable and timely steps to prevent foreseeable harm. This might include implementing sound procedures, addressing emerging risks, and responding appropriately when warning signs are clear.

- Making things worse – Negligent action. Acts or decisions that foreseeably create or aggravate harm — for example, ignoring evidence, mishandling complaints, or enforcing policies that intensify vulnerability or risk.

- Doing nothing – Passive inaction. A failure to act when an institution knows, or ought reasonably to know, that intervention is required. Courts are generally reluctant to impose broad affirmative duties, but complete inaction in the face of foreseeable harm can potentially still give rise to liability under existing legal frameworks such as negligence or equality law.

The triangle shows how these behaviours relate to one another.

- At the bottom left lies making things worse – acts of commission that cause harm.

- At the bottom right, doing nothing – omissions or institutional inertia.

- At the top, making things better – protective, preventive steps taken with reasonable care.

The law, as it stands, occupies mainly the lower portion of the triangle. It is most comfortable along the base, where harmful acts are distinguished from mere inaction. The upper space – proactive prevention – sits largely outside the common-law field.

Cause, not prevent

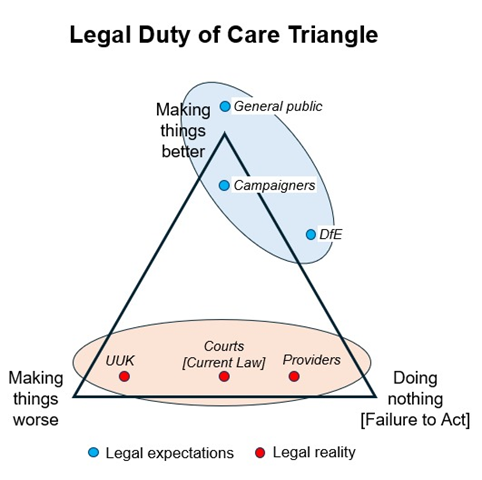

One organisation sits in a particularly revealing place on the triangle – Universities UK (UUK).

Unlike the Department for Education or the courts, UUK has consistently described universities as already having a common law “general duty of care.” At first glance, that sounds like agreement with campaigners – but it isn’t.

What UUK actually means is a general duty not to cause harm through acts or omissions. It’s a subtle but crucial difference. It is referring to a reactive duty – one concerned with causation of harm, not prevention of reasonably foreseeable harm.

For example, if an institution takes a clear and identifiable act — such as issuing incorrect information, mishandling a process, or withdrawing essential support — and that conduct foreseeably causes or worsens harm, the law may treat the situation as one of direct causation.

If the institution then fails to correct or mitigate the error once aware of it, that omission becomes part of the same chain of causation.In such cases, the duty extends to omissions only when they form part of that chain, not where the institution simply fails to prevent a wider or unrelated risk..

In legal terms, this remains a negative duty (to avoid causing harm), not a positive duty (to take steps to prevent it). It recognises that omissions can sometimes “cause” harm where there’s a direct link, but it doesn’t impose any obligation to foresee and prevent it.

That distinction between cause and prevent defines UUK’s unique position. It sits within the existing boundaries of common law because it focuses on reactive duties — those that arise only when harm has already been caused.

This is the source of much public confusion: UUK uses the language of care to describe a legal concept concerned solely with causation.

The result is a comforting vocabulary that sounds protective but, in practice, stops at the point of legal liability.

When UUK says that universities already have a duty of care, it means a duty not to make things worse, rather than a duty to make things better. The same words – but different worlds.

Responsibility without liability

The original petition did not ask for improved guidance or voluntary measures. It called for a statutory legal duty of care – a clearly defined obligation in law requiring universities to take reasonable steps to protect students from foreseeable harm.

Yet when the government issued its 2023 petition response, it appeared to suggest that such a duty already existed. The statement claimed that universities “already have a general duty of care to not cause harm to their students” and “are expected to act reasonably to protect the health, safety and welfare of their students”. Language that sounded legal but was not.

At that stage, the Department for Education (DfE) was describing something closer to an ethical or moral responsibility – a general expectation that institutions should act responsibly – while borrowing the vocabulary of law. It gave the public the reassurance of legal certainty without any of its substance. The explicit legal framing emerged only later.

In response to a Parliamentary Question tabled shortly before the Westminster Hall debate, Minister Robert Halfon used the phrase “law of negligence.”

This was the first time the Department had explicitly tied its earlier petition response to that legal doctrine, implying that it had always referred to common-law principles. From that point onward, this became the Department’s preferred line – not as clarification, but as post-hoc justification.

Then, in early 2025, Janet Daby MP, Minister for Children, Families and Wellbeing in the Department for Education (DfE). appeared to reset the conversation. In a Parliamentary Question response she acknowledged that a duty of care may arise in certain circumstances, but that this would be a matter for the courts to determine. This was a noticeable change in tone – a more candid admission that no general legal duty exists and that the issue remains legally unsettled.

Her statement offered welcome clarity after years of obfuscation, though it still stopped short of committing the Department to legislative reform.

The same careful phrasing was subsequently used in a formal letter from the Department dated 16 July 2025, confirming that this “reset” had become its official position:

A duty of care in higher education may arise in certain circumstances. Such circumstances would be a matter for the courts to decide… The common law allows flexibility, without the potential rigidity that may arise from codifying a statutory duty.

The evolution reveals rhetorical movement but positional continuity.

The Department has, in reality, always occupied the same place – outside the legal boundary of the triangle, in the zone of responsibility without liability. What changed was not the position itself but the language used to describe it.

The 2023 response disguised that position through legal-sounding reassurance; the 2025 reset finally admitted what had been true all along — that no general legal duty exists and that the matter rests with the courts. In other words, DfE continues to speak of care, support and best practice, but refuses to define those commitments in law.

When the risk is radicalisation, the government imposes a statutory Prevent Duty, but when the risk is harm to students, it hides behind the flexibility of common law.

The real world

Once the triangle exists, it becomes possible to plot where each actor sits – and, crucially, what that reveals about how they understand “duty of care.”

At the bottom centre sit the courts, which define the legal floor of responsibility. Their judgments focus on causation, proximity, and foreseeability – deciding whether an act or omission was sufficiently connected to the harm suffered to give rise to a duty.

They don’t occupy either corner of the base because they navigate between them – recognising liability for acts that make things worse, but rarely for omissions that cause or contribute to the problem, or simply fail to make things better.

Their position therefore represents the balancing point of the common law – the threshold where duty ends and moral expectation begins.

Along that same base lies UUK, which has translated the courts’ caution into sector orthodoxy. UUK’s “general duty not to cause harm” adopts the courts’ reasoning as a policy principle – treating the lower boundary of the triangle as the full extent of universities’ obligations. In effect, the courts define the boundary, and UUK defends it.

Moving rightwards along the base, universities sit midway between the courts and the “doing nothing” corner, invoking autonomy and professional judgment to argue that support and intervention are matters of discretion rather than law.

Then just outside that edge sits the Department for Education, which talks in moral terms of “responsibility” and “care” but refuses to anchor those ideas in law. It operates in the space of responsibility without liability.

Above them all, beyond the apex marked “making things better,” lies public expectation – the belief that institutions should act to prevent foreseeable harm, not merely avoid causing it.

This moral position sits outside the present legal framework but defines the social direction of travel.

Between these two levels – between the courts’ current legal boundary and the moral high ground of public expectation – lies the proposed statutory duty of care.

It would still sit along the base axis of law, midway between making things worse and doing nothing, but it would rise vertically within the triangle – recognising that the law must not only avoid harm but also act to prevent it where reasonably foreseeable, just as Parliament has already required through the Prevent Duty.

In that sense, a statutory duty would lift the legal threshold upward, not outward – retaining the structure of the common law but extending its reach to address public expectation.

The triangle naturally narrows as it rises. In legal terms, that tapering reflects how rarely the courts recognise proactive duties. A statutory duty of care would not alter the shape of the triangle but would raise the level at which the law operates, making what is now exceptional – acting to prevent harm – part of the ordinary standard of care.

Drawing the line

The Legal Duty of Care Triangle is not just a visual aid, it’s a question. Every dot on it represents a choice about where responsibility should sit – inside or outside the field of law.

Parliament now faces that same choice. The forthcoming debate is not about whether universities should care for their students – everyone agrees they should. It is about whether that care should be accountable.

Placing the point inside the triangle would mean recognising a statutory legal duty of care – a defined obligation that lifts the existing common-law threshold so that institutions must take reasonable steps to prevent foreseeable harm. It would introduce a clear standard of accountability, giving students and families a route to justice when that standard is not met.

Placing the point outside the triangle leaves the status quo intact – a landscape of guidance, codes, and voluntary commitments that sound caring but lack consequence when breached. It maintains responsibility without liability – expectation without enforcement.

That is the question before Parliament. Where should the point be placed? Inside the triangle, where care carries accountability – or outside, where it does not?

The triangle invites everyone – not just lawyers or policymakers – to think about where they believe accountability should begin. It is less about identifying where universities are and more about asking where they should be in terms of legal accountability.

For a university that sees its role purely as educational delivery, the point may hover near the base – within the comfort zone of “doing nothing” unless compelled. But that is the vending machine model of higher education – inputs go in, outputs come out, but no awareness or responsibility exists between the two.

When things go wrong, the machine insists it functioned as designed – and no one accepts responsibility for the harm that results.

For institutions that recognise their wider duty to protect students from reasonably foreseeable harm, the point moves upward, toward “making things better.”

The purpose of our campaign is not to redraw the triangle but to raise the floor – bringing the baseline of law closer to where most people assume it already stands.

A statutory duty of care would not expand the triangle. It would ensure that its foundation reflects modern expectations of safety, fairness, and accountability in higher education.

What that duty would look like in practice – the mechanisms, policies, and safeguards that would follow are arguments for another day.

The purpose here is simpler – to define the space where that conversation must take place – inside the triangle, where duty carries accountability.