Last week culminated in predictable sound and fury around certain higher education-specific aspects of the Augar report, even though we all knew they were coming. These included the proposed new fee level of £7,500 (which grabbed most of the headlines), a stinging critique of university spending (and saving, in the form of surplus), the prospect of possible restrictions on access to student finance based on tariff, and the removal of funding for foundation years.

It’s understandable that in the first week of Augar, universities would look first at how that package might impact on them directly, to comment on that straight away, and make arguments about their role and value. Indeed, in our own precis, we focused on exactly that. But looking beyond the initial response, it’s critical that the sector now considers the message in the substance in this review.

Two parallel approaches

One way to read the underlying narrative of the Augar report is that it represents an indictment of two parallel education policy approaches, pursued by multiple, and politically different, governments over the last fifteen or so years. These parallel approaches have treated higher education and further education in radically divergent and – the report implies – radically incompatible ways.

In short, the parallel policy approaches can be summed up as follows:

The government has pushed higher education towards a more market-like system, which Augar says has gone so far as to become dysfunctional (with symptoms ranging from the total lack of price competition to grade inflation, unconditional offers and other much-discussed system problems). But he also says that, in parallel, further education has been subjected by governments to a policy of intense, highly bureaucratic central planning, tinkering and micro-management, which has also become dysfunctional.

And in the report, there’s an obvious but important amplifier to this observation in the conclusion that higher education is probably over-funded, and further education is scandalously underfunded.

Incompatible?

Augar starts to unpack the ways this deep incompatibility has effects which trickle down to cause a wide range of serious practical problems on the ground, and argues that this has become a significant barrier to the performance of England’s skills system as a whole, reducing the national value of that system, and impeding the ambitions of many students in it. It is also argued to be a source of immense unfairness and socially regressive outcomes, which can no longer be justified.

Nobody thinks that colleges and universities are the same thing, or should be treated in exactly the same way. But the review says that the huge gulf of treatment – on lines of regulation, funding and other issues – simply is not rigorous from a philosophical or policy design standpoint. And it must change.

Reading Augar’s report, there are numerous comparisons to draw between higher and further education – sometimes these are made explicit, and other times they are left to the reader to discover as you move between sections.

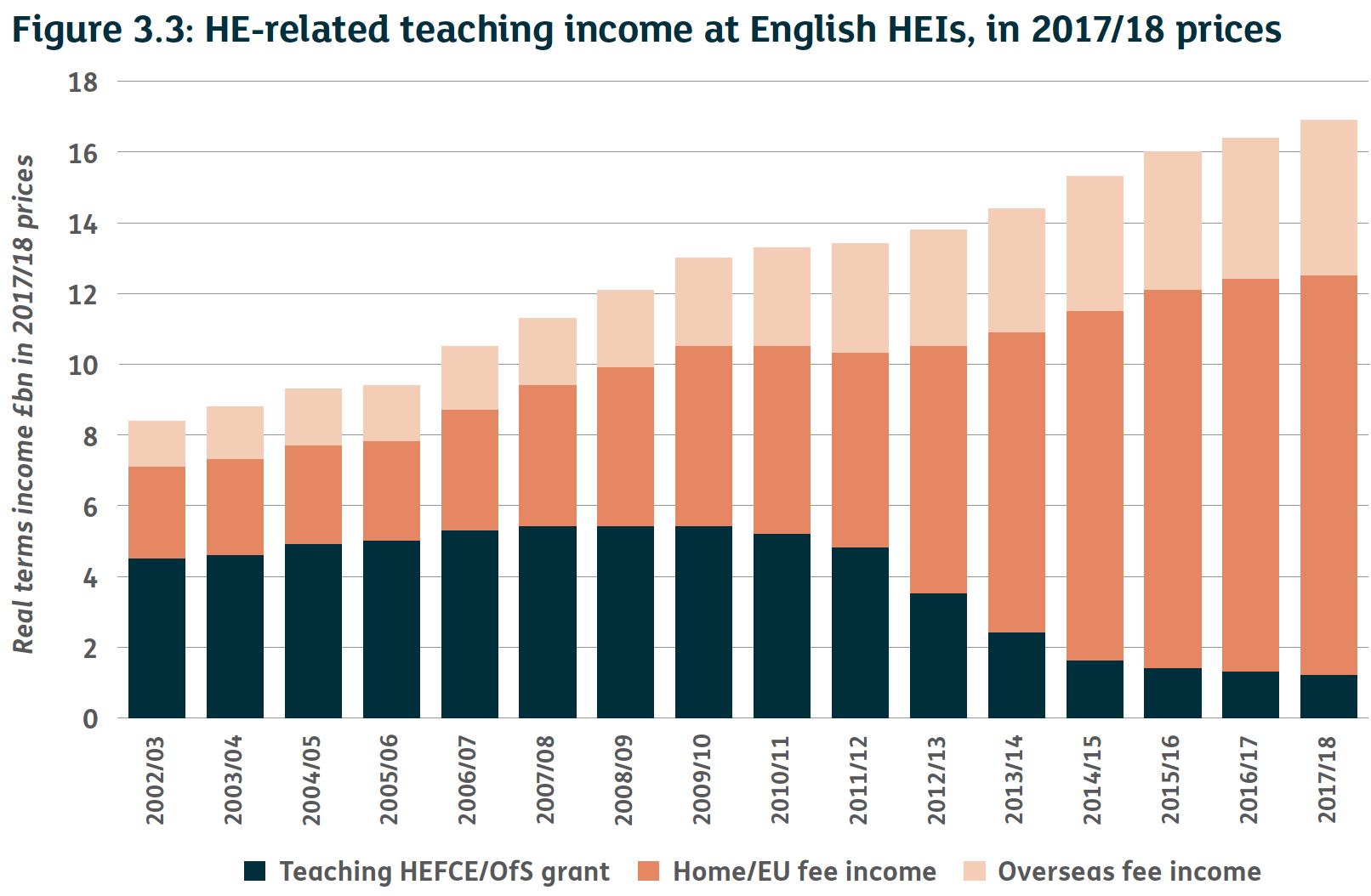

For example, this the graph on the bottom of p.67….

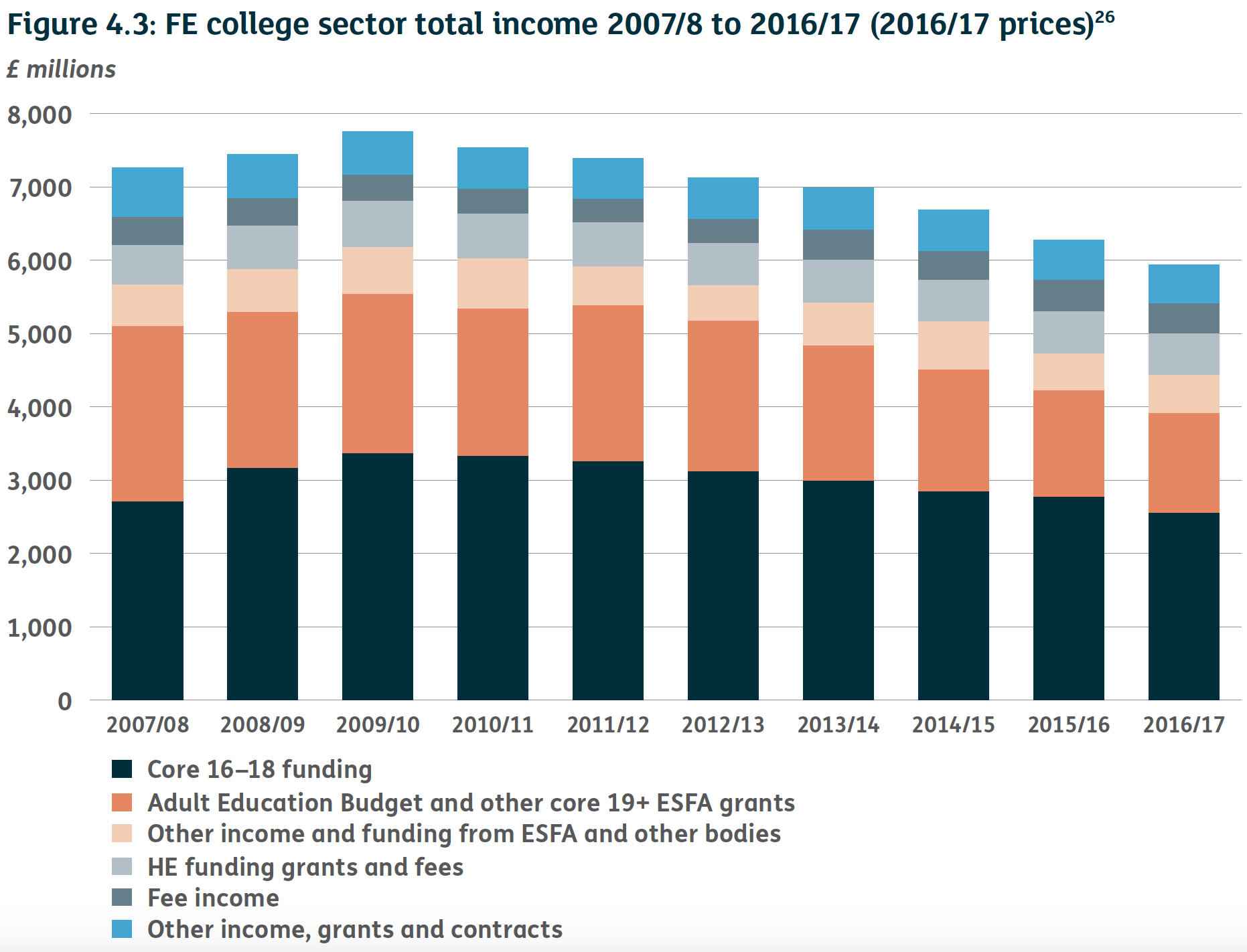

….and the one on the top of p.120.

The former shows higher education-related teaching income at English higher education providers, the latter further education sector total income.

Now, keep in mind the social background of the majority of students who learn in each sector, and you can form your own judgement about whether it is morally acceptable to balance educational resource across society in this way.

Crossing the gulf

It would be a real failing if the focus of the coming debate is only dragged back to issues concerned with higher education. Augar himself hints at the risks of this in his own foreword to the report, with a sharp comment about the strong higher education background bias that pervades modern journalism.

But this review was never really about the fee cap or its attendant issues, and if we’re going to understand it properly and see its potential we have to push those points to the margins and see the bigger picture.

It’s clear that the higher education sector does many wonderful things and that it remains, in all its diverse glory, a jewel in the national crown. People in the sector should be rightly proud of that. But, to paraphrase a well-known critique, for too long we have regarded the low fortunes of the further education sector as somebody else’s problem.

Chapter 6 of the report exposes starkly how much further education is swamped in a regime of byzantine complexity. We think policy in higher education is complex, but it’s easy by comparison. So to give the Augar report its proper dues, we all need to sit down with a strong coffee and get our heads around this stuff, how it compares to higher education policy and how the two sectors might become better integrated in a deep sense, with a genuinely fairer settlement, at both the system and institutional levels.

Augar has helped untangle it about as clearly as might be possible, and the job for further and higher education is now to try and stitch it back together again. The pages of the report that set out the purposes of a post-compulsory education system could be a valuable reference point. We might begin by acknowledging, as the Augar panel does, the civic mission of colleges, and recognising their role in the research, innovation and scholarship infrastructure, as well as in the provision of skills and access to education.

This asks us to move beyond the current hotchpotch of further and higher education partnerships and local arrangements and into the realm of a coherent strategy that genuinely crosses the gulf. That is the biggest challenge posed by Philip Augar. Will anyone take it up?

[…] https://wonkhe.com/blogs/crossing-the-gulf-the-true-challenge-of-augar/ […]