The British government is trying to sell off parts of the growing English student loan mountain to the private sector in small – and they hope, not newsworthy – slices. But so far this privatisation has not been going well. Investors might be beginning to realise that they are buying potentially toxic assets – so they will start to factor in the risk that a future government will write off this debt.

After 2012, English fees had suddenly and unjustifiably become the highest in the world. The people cajoled into taking out those debts were children when they made the decision to go to university. Who would pay a “market price” to buy debt incurred by children who could not possibly have understood what they were entering into, the international marketplace they had suddenly become a part of, and how their future earnings would be sold to private companies?

Selling the future cheaply

At the end of November 2017, you may not have noticed the UK government announce that it would lose £800 million on the sale of just 8.6% of its pre-2012 student loans. The government plans to quietly sell more of these loans over the next five years. So far they have shown little interest in a public debate being opened up on this issue, and millions of students and former students discussing who their loans might be sold to, or for how much.

It may turn out that future loans are sold for even less, with an even bigger loss. Thomas Hale, writing in the Financial Times in January, concluded that:

“The debate around the discount on the sale has important implications not only for the value of tens of billions of loans still sitting on the government’s accounts, but also for the overall viability (and political acceptability) of the current funding model for English higher education, and for education models in many other economies around the world.”

Because the current government realised that in the future a very different type of government might want to unravel this mess, the (now former) universities minister Jo Johnson attached a promise to the sale. Any future government would have to compensate the investors who bought the loans if, in what is called a “democratic risk”, the electorate of Britain decided to vote into power a government that would abolish new loans and fees. That future government would then have to look into how to recompense existing student loan borrowers who were simply unlucky enough to have been born at the wrong time.

Of course, any future government can explain that it was not elected to be tied to the venality of past administrations. It can also point out that those investors buying student loans took a risk. Part of that risk was that a government might be elected that would not look kindly on such profiteering. Any compensation should be due to students and graduates, not those that led us into the financial crash of 2008, or those who tried to profit out of the decision of 17-year-old children to go to university.

Highest fees or not?

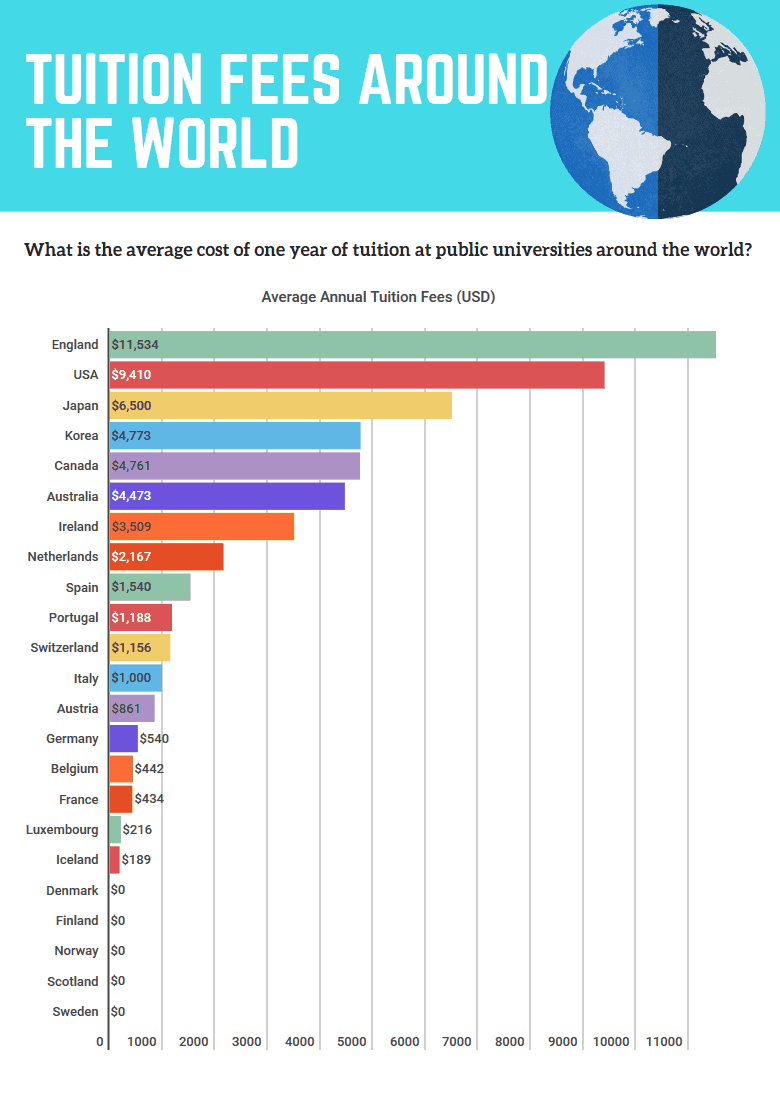

What are the incentives for those currently in government to keep on propping up the current system? The key incentive appears to be that it has made it possible for England to have – on some measures – the highest student fees in the world. Research by the creator of the website “student loan calculator” – drawing on a large number of sources – was published in March 2017 and is illustrated in the diagram below. The key comparator is between the England and the USA. OECD statistics report that the average annual fee for a bachelor’s degree in the USA is $8,202 at a public institution as compared to $9,019 a few years ago. The figures will change year by year – but England remains a substantially more expensive place to study than the USA, and both countries are the two of most unequal of OECD countries.

A year ago, the Economist published alternative figures suggesting that in many US states it was more expensive to go to university than in the England. The OECD will have taken in factors other than just the headline fees, such as bursaries. But worrying unduly about such comparisons misses the main issue – both England and the USA are out of line with the rest of the world.

Source: Student Loan Calculator

Some people criticise the chart above by pointing out that a few of the extreme elite private US universities have much higher fees that the US average. However, the same would be true of a very small but growing number of private UK universities, and does not affect the large majority of students and young adults.

Even if the line for England is adjusted to make it the ‘UK average’, it would still be longer than the US line. England contains such a high proportion of students in all of the UK because the populations of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are small in comparison. This graph is a fair reflection of the international distribution although it misses out important countries such as Chile. But it does highlight the position of Scotland, and it would be good if Northern Ireland and Wales were added to it in future.

The Scottish way

In Scotland, the debate has moved on from fees. A report published in November 2017 suggested that all university students in Scotland should have a legal right to £8,100 a year to live on, and half that amount when they are at college. The tricky question of how to fund such maintenance payments is rising up the agenda.

If Scotland wanted to aim higher it would have to become an independent country. Then it would have the political power to choose to do this, as Lorenza Antonucci says:

“A truly transformative move would be to implement a Nordic system of student support, where the absence of tuition fees is accompanied by a generous and (above all) universal system of grants (and loans). In this system, grants would be guaranteed to all students, regardless of parental income. This move would be a radical departure from the British system of HE which is based on individual investment.”

Brexit – better than all the rest?

As Brexit looms closer, various schemes for Britain to “find new markets” will be touted. One approach will be to suggest that because our higher education is the most expensive in the world, that means that (in the immortal words of Tina Turner) it must also be “simply the best, better than all the rest”. We once said the same about our banks.

Putting too many eggs in one basket is unwise. Claiming that something must be good because it is expensive is dangerous. Suddenly making it very expensive overnight, as occurred when fees tripled from £3,000 to £9,000 a year and then suggesting that the price reflects sudden new found quality assumes that you are aiming your marketing at some very stupid people who do not understand when they are being conned.

The raising of fees might be ever so slightly defendable, as a short-term fix for when the global financial crisis hit. It prevented mass redundancies in universities. But as a long-term strategy, it moved English higher education closer to becoming a finishing school for the less discerning and less able of the world’s very richest children. For these children, as Tina Turner also said (in Simply the Best), we can provide: “a lifetime of promises and a world of dreams”.

Hello,

Dear Applicant, Are you in any financial crisis, do you have a low credit score and you are finding it hard to obtain capital service from local banks and other financial institutes? Here is your chance to obtain a financial service from our company. We offer all kind of loan to individual companies at 2% interest rate.

If you need a loan do not hesitate to contact us below via.

Name: Mr. Cliff David

Email: safefinancialservices07@gmail.com

WhatsApp Number:+919205645829