Our skills system has developed what I call a “missing middle” — a relative lack of higher technical qualifications at levels 4 and 5 (qualifications that are beyond what we think of as being school level but below bachelor’s degrees).

In my latest report for the Gatsby Foundation, I explore how we got to this point, how our provision at these levels compares with other countries, and what could be done to address this gap in our system.

Where is higher technical education?

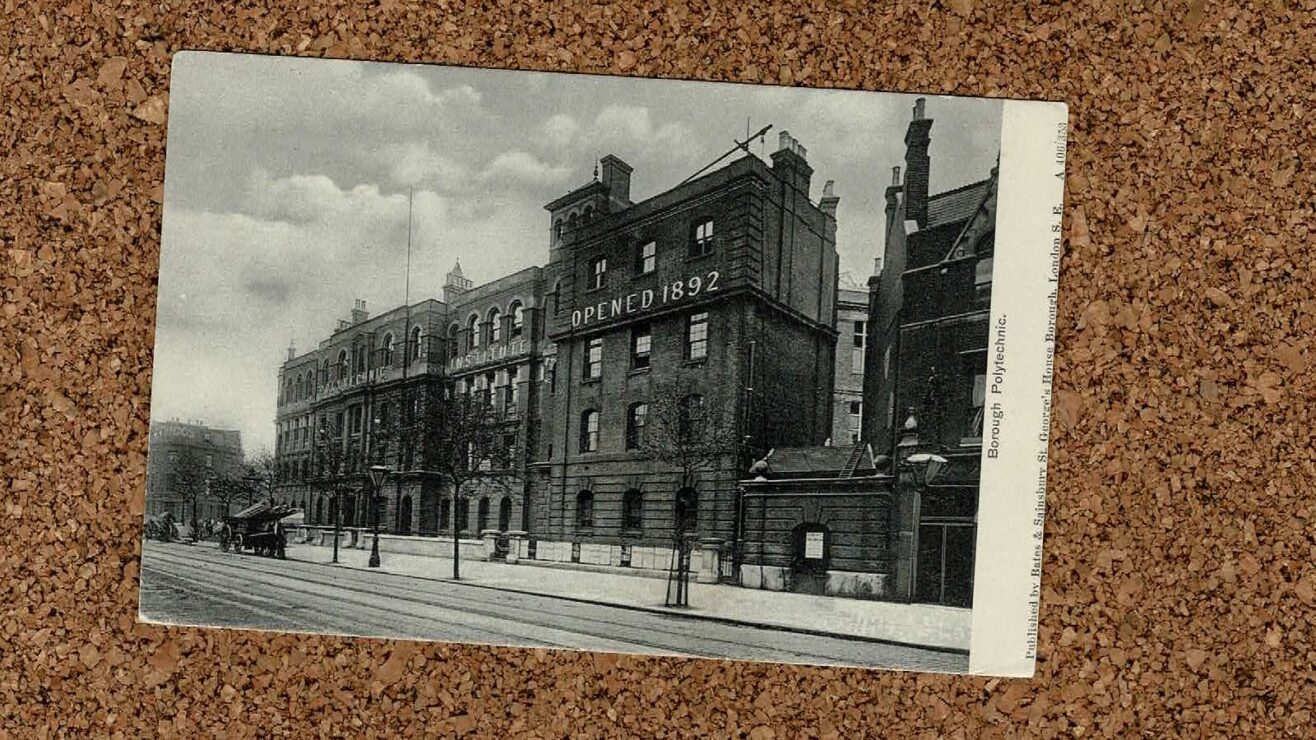

This missing middle is a peculiar feature of the modern English technical education system, and we must look in part to history to understand why this is. Within the last century there have been cyclical policy proposals and attempts to address the issue, typically driven by particular skills needs of the time.

Higher nationals were introduced in the 1920s to tackle the engineering skills shortage post World War I. In the mid-1950s, the government identified a shortfall in the supply of mid-level technologists, so proposed to increase supply by 50% through the new diploma in technology. By the 1960s, Higher technical education (HTE) qualifications like higher national diplomas played a large role as entry routes into the professions. For example, in engineering, HTE served a clear purpose in preparing people for particular occupations.

In the late 1990s, the Dearing report proposed to concentrate HE expansion in HNCs and HNDs. By the early 2000s, foundation degrees were created with the expectation that these would become both a free-standing, work-related qualification and an avenue of progression, reflecting labour market demand for intermediate skills.

And yet, despite these calls for more HTE skills in the labour market, multiple factors over the same time period actually caused a decline in HTE, at least as a share of all higher education. This has been widely recognised, and the terms of reference for the current review of post-18 education and funding note the lack of alternative technical routes to three-year degrees.

What were these factors? In the 1960s, the Robbins report voiced little enthusiasm for part-time students, or for qualifications below bachelor’s level. Professions like engineering, teaching and nursing came to expect entrants to the profession to have bachelor’s degrees. The polytechnics, with their distinctive technical and vocational mission, are no longer with us. More recently, the collapse of part-time numbers in HE has been devastating for an HTE system which is dominated by part-timers. But we still have a clear need for higher technical skills in the labour market, and it still needs to be addressed.

International comparisons

My report demonstrates that England is also an outlier by international standards. Even within the UK, Scotland, through sustained support for higher nationals usually delivered in FE colleges, maintains a much larger higher technical sector than England. Around the world, mid-level qualifications have flourished where there are strong links between employers and providers, streamlined progression opportunities for students, flexible forms of provision for adults, and other initiatives that have developed HTE qualifications which are more than just pale imitations of bachelor’s degrees.

In Sweden, higher vocational education programmes require partnerships between employers and training providers, and target specific skills requirements. In Japan, the elite Kosen institutions offer programmes that combine the equivalent of an A-level with two years of post-secondary technical education, easing the path from school to higher level education and training.

In Switzerland, professional examinations allow adults to follow flexible routes, with no required programmes of study, to a final assessment. These offers have what marketers would describe as unique selling points, which are of key importance in establishing a clear, firm role for higher technical education.

So what can, and should, be done about the missing middle? Step forward two potential vehicles of reform, both currently in train—the review of levels 4-5 and the review of post-18 education and funding. Secretary of State Damian Hinds’ speech last week provided an indication of the policy direction and underlined how higher technical education is going to remain firmly on the policy agenda. My own report aims to contribute to that debate, by looking at the past, learning from the experience of other countries, and suggesting directions for the future.

Do the higher level Apprenticeships standards not fit the qualification ‘gap’ to which you refer?

Dear Paul – you are absolutely right! Although, as the full report argues, we need to make one change to make this a reality. At present apprenticeship standards in England differ from most apprenticeship systems in other countries, in that they do not allow people to pursue the end-point assessment and obtain the qualification without going through an apprenticeship. For example, in Norway, about one third of those obtaining journeyman certificates obtain it directly, through the examination. If level 4 and 5 apprenticeship standards were to grant this principle, opening them up to individuals who already have most of the… Read more »

Interesting article Simon. Lots to think about. In general, I agree that we need a rethink of how qualifications and training are defined in the 21st Century. I am a product of the polytechnic system from 30 years ago when I obtained my HND in Physical Science (NQF Level 5). Today’s many employers do not understand the vocational qualification standards because they equate everything mostly on the free standing & trusted academic level standards of GCSE, A levels and Degrees. Today, the vocational standards are hard to understand. It is also difficult to equate their value in relation to the… Read more »