The idea that students should passively consume their education is widely regarded by academics as a bad one.

For some students, knowing that their tuition fees are paying their lecturers’ wages may engender unrealistic expectations around the quantity and/or type of input they should receive.

These expectations may also be accompanied by a sense of entitlement among some students in terms of grade outcomes.

Students as consumers

The idea that students’ consumer identities should be reinforced thus seems to be at odds with what educators perceive to be needed for creating optimal teaching and learning experiences, and research supports this.

For example, data I have collected from undergraduate home students in England suggests that those who identify more strongly as consumers have poorer academic outcomes than those with weaker consumer identities.

Furthermore, student “consumers” are more likely to have goals that are related to their performance, e.g., passing a test, than goals related to developing their understanding, and so they adopt more passive learning strategies, such as rote memorisation.

In addition, students who complain more about their course (a “symptom” of marketised environments whereby customer feedback is encouraged) are also more likely to report using superficial learning strategies, which are associated with poorer attainment.

When you look at the data, however, the extent to which students actually identify as consumers may be surprising. The data do not support the belief that most students identify strongly as consumers. For example, one study measured levels of agreement to statements from a student customer orientation questionnaire in over 600 undergraduates in England.

Example statements included: “As long as I complete all of my assignments, I deserve a good grade”, and “The main purpose of my university education is to maximise my ability to earn money”.

The mean agreement score was fairly low, and comparable to a similar study of almost 800 students, and another study of American students. How does this reconcile with the perception among many educators of students identifying as consumers?

A student identity typology

It is useful to look at the bigger picture and understand students’ supposed “consumer” identities alongside the more traditional identity of student as scholar or learner. In the same study that first measured consumer identities among students in England, Bunce et al also measured learner identity.

They found that students, on average, had a strong learner identity (measured with items such as “I read relevant sources to learn more about my subject at university” and “I feel most satisfied when I work hard to learn something”).

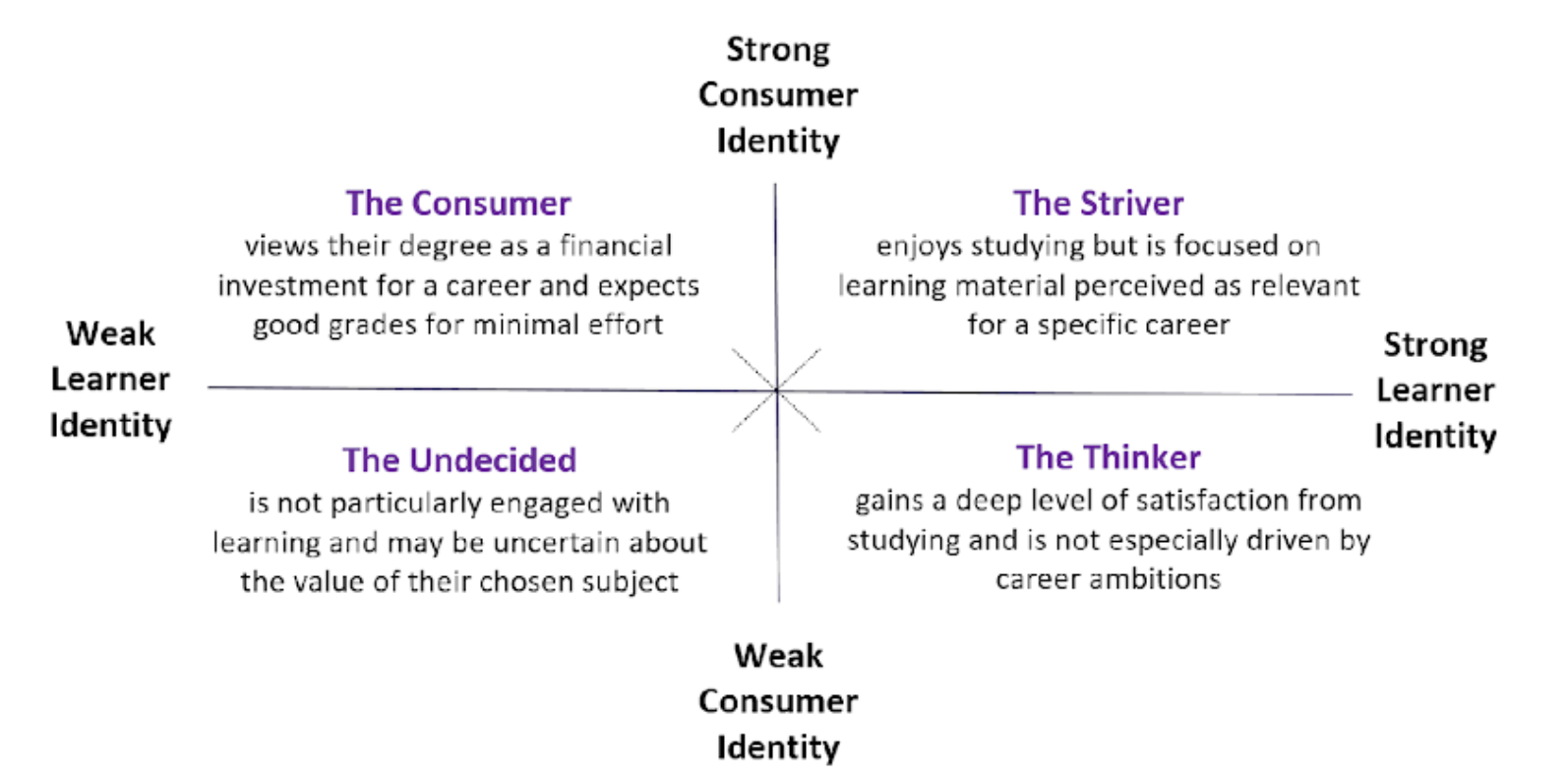

However, rather than viewing consumer identity and learner identity as opposite ends of a continuum, I suggest that these two dimensions of a student’s self-concept can sit alongside each other, and this can be conceptualised in a four-way typology (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A four-way typology of students according to the strength of their learner and consumer identities

If we consider students’ identities as consumers and learners as two separate ones, then we can start to understand the paradox between the idea that modern students are passive “consumers” versus students’ perceptions of themselves as learners.

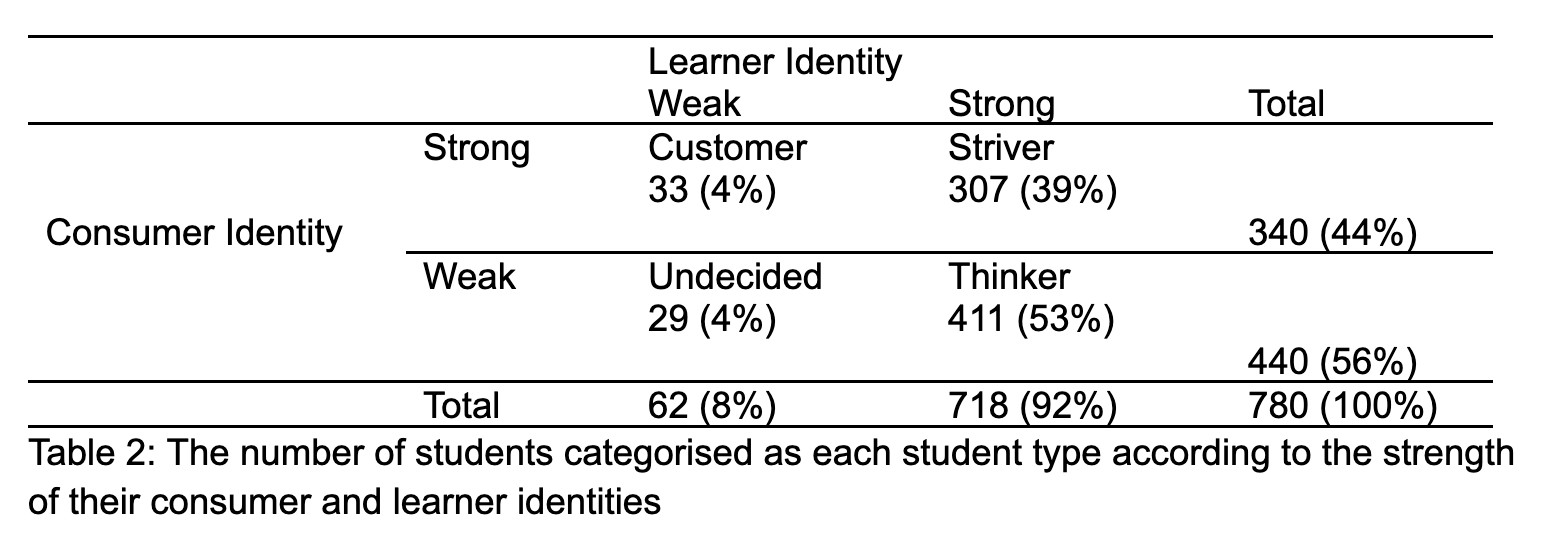

I categorised students according to this four-way typology, as shown in Table 1 (originally presented in Taylor Bunce et al). The number of individual students who identified purely as “Customers” (strong consumer identity, weak learner identity) was almost non-existent (4 per cent), but the number of students who identified strongly as consumers and learners (Strivers) was rather high at 39 per cent.

Interestingly, there was an even greater number of students who had a weak consumer identity and strong learner identity (“Thinkers”, 53 per cent). Therefore, looking at these two dimensions of students’ self-concepts alongside each other presents a more nuanced and complex picture of how individual students are seeing themselves.

Consuming and learning

One might argue that helping students to become “Strivers” would actually confer them the best ”value” of university. They would still see learning as their responsibility and have study goals that are related to deepening their understanding, but they would also view their degree as a financial investment.

In this way, rather than simply passively consuming their education, they become more active consumers, making the most of services available to them at university to support their career ambitions. When I asked students to reflect on their consumer and learner identities as part of a teaching session, students recognise that being a successful student means: “studying [and] using the services available at university”, and “engaging in learning activities and having a serious focus towards my career”.

A practical tool to support student identities

Students are arguably entitled to receive support from institutions to help them navigate the potential tensions that may arise from holding conceptions of themselves as both consumers and learners.

To this end, I have led the development of a workshop that educators can use with students that enables students to assess, reflect on, and balance these two aspects of their student self-concepts (see www.brookes.ac.uk/SIIP). Initial evaluation data from psychology undergraduates suggests that this workshop has the potential to increase the number of student “Strivers” by supporting them to think more holistically about the opportunities afforded by their degree for their futures.

My plea to educators is to overcome the notion that students consuming education is inherently “bad”. I suggest that we want students to be active, engaged, and motivated consumers, who work with us to ensure they get the best value from their time spent at university.

We have responsibility for supporting students to graduate with knowledge, skills, and a qualification to enable both individual prosperity and societal improvement. To enable this, we should support students to develop a more nuanced approach to understanding their identities as both learners and consumers – after all, they are paying our wages.

Thankyou, that’s great news – most students are thinkers! So what’s the problem? If most of the people who pay our wages actually agree, despite all the very real economic challenges they face, with a quite ‘traditional’ love of learning for its own sake, and those students who adopt this approach are the most likely to succeed in their studies, why on earth should we indoctrinate them away from this wonderful love of learning into a narrow cult of seeing themselves as financial investors? Again and again we see the crassly consumerist model of education that policymakers and university managers… Read more »