Once again the combined voices of the established higher education sector are cheering for the Peers of the Realm.

The noble Lords have inflicted another embarrassing defeat for the government over the Higher Education and Research Bill, this time inserting a new clause preventing a link between the Teaching Excellence Framework and differential levels of fees.

Does this mean that the TEF is dead? Probably not. Does it mean that tuition fees will no longer be increased by the rate of inflation? Probably not either. The cross-party group of opposition Lords behind this amendment made it clear that they were not opposed to increasing fees by inflation, and many also stated that they supported some form of Teaching Excellence Framework as a means to improve quality.

Indeed, the matter highlights the splits within the group of TEF’s opponents. Some, including NUS and UCU, are opposed to any increase in fees whatsoever. However, most of the Lords arguing against TEF (and one suspects many vice chancellors) simply want to take the inflationary fee increase and quietly dispose of the burden of TEF. In the long run, it’s unlikely either group will get what they want: fees will rise, and some variant of the TEF will probably limp on.

It’s important to stress that yesterday’s vote will probably not have much of an effect on TEF2, the results of which are due to be released in May, and for which universities have submitted their applications. Higher education providers will still be rated Gold, Silver and Bronze in the exercise. As things stand, the 2018 statutory instrument amending tuition fee regulations would simply not be able to set differential rates based on these outcomes. Yet the TEF will still have happened, with all the inevitable media fanfare and impact on reputations.

The critical influence might come in TEF year 3 (results to be released in 2018, determining fees in 2019), and whether universities would continue to enter without the incentive of increased fees. However, the government could simply deny the sector its fee increase by refusing to issue a statutory instrument, perhaps if not enough universities chose to enter. The prospect of such a standoff is unlikely, but as a possible endpoint will no doubt influence both sides’ negotiating position. Then there’s the ‘legacy effect’ of TEF2 – universities might enter TEF3 for the sake of reputation: to double down on a successful outcome, or (more likely) correct a negative one – but things get pretty unclear here in any case.

Words and meanings

Looking at the language of the opposition peers speaking in yesterday’s debate, it appears that the amendment may well be stalling tactic rather than an attempt to completely derail TEF and its link with fees.

As Lord Kerslake made clear, if anything, the House’s objection is that fee increases will not be universally available to universities as a result of TEF:

“I have no doubt that a properly argued case for further inflation-level increases will, and indeed should, get the support of Parliament. The issue here comes from the Government’s plans to circumvent the debate on fees and allow inflation increases only for those universities that have achieved silver or gold rankings…

“There is a strong case for promoting teaching excellence and for allowing student fees to rise in order to reflect increasing costs. However, putting the two together in the way the Government are currently proposing is both ill-judged and unfair…

“It is really important to say that there is no need for universities to be deprived of the opportunity for inflation increases.”

Baroness Wolf’s was one of several to object to the TEF’s metrics “in its current state”, and Lord Lipsey – an outspoken critic of the National Student Survey in particular – demanded that the government “[give] time for the TEF to settle down before they [bring] in the fees link”. Baroness Blackstone called it “putting the cart before the horse”, whilst Lord Stevenson was more effusive in his support for both fee increases and some form of eventual link with a quality improvement system:

“There is no reason at all why the Government do not bring forward a statutory instrument [to raise fees] under the terms of the Act that make provision for that power to do so. There is no need, in fact, to anticipate what may be a good system for measuring higher education by linking it to the teaching quality that has been discovered by a half-baked scheme that is not yet half way through its pilot system.

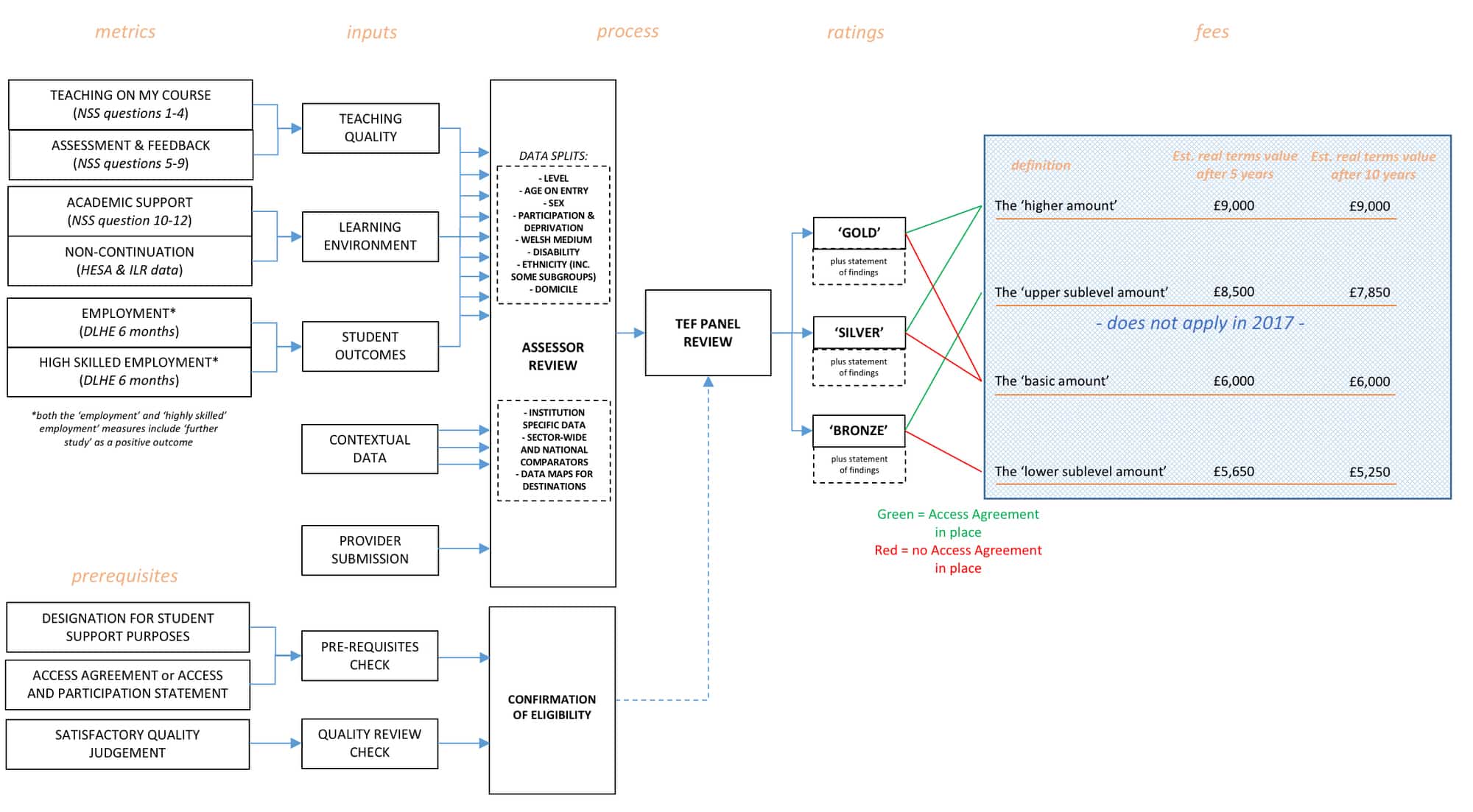

The debate in the House of Lords has frequently been diverted into disputes over the ins and outs of what Wonkhe has called ‘the incredible machine’. This is inevitably a subject which every wonk and their dog has view on, and the simple coincidence of having several such wonks in the Lords is one of the reasons for this standoff.

The matters taken issue with in TEF’s current design appear to include (but are by no means limited to):

- the use of NSS as a core metric;

- the use of employment data and potential use of LEO salary data in future iterations;

- the use of benchmarking, which ensures a ‘relative’ rating of institutions rather than an ‘absolute’ rating.

Taking all this into account begs the question: what would a Peer Approved (very different to peer reviewed) TEF look like? Would it be workable? And in whose interests would it really work for?

Oiling the machine

The focus on the ins and outs of the TEF’s methodology suggests that peers are not contented to see future versions of the exercise designed as have the first two: by a small team of overworked officials in DfE and HEFCE with only notional consultation with the sector. There is a reasonable case to be made that this is simply too much executive power for the government to hold over universities’ heads.

Thus the critical issue may not prove to be so much the specific methodology behind TEF as much as its governance and oversight. As Mark wrote on Monday, the next crunch here may come with Amendment 72, which would require affirmative Parliamentary approval for the future design of TEF and associated fee increase.

One wonders if this would really make TEF any better. If you think TEF is politicised and somewhat unfocused now, just wait until politicians and peers – each with their own interests to champion and axes to grind – get their hands on the detail. One has to feel a little bit sorry for those officials cursed with designing TEF. They were tasked with a difficult enough job by their minister before; if the minutiae of their work were subject to the approval of both Houses of Parliament, it might be completely unworkable. And that’s before we even get into the thorny matter of a subject-level TEF.

Parliamentary oversight of ‘the incredible machine’ would also make it vulnerable to bias and the sway of special interests. The aforementioned matter of benchmarking is particularly tricky, as it will lead to several recognised ‘prestigious’ – or as Baroness Wolf chose to call them, “better known” – universities doing badly compared to less prestigious competitors. The overrepresentation of a particular subsection of universities in Parliament is well known. Roughly one third of MPs attended just six universities: Oxford, Cambridge, LSE, Edinburgh, Manchester and Durham. The peers most involved in the debate over the ins and outs of the TEF are predominantly linked – in both paid, unpaid, or historical capacities – to Russell Group and pre-92 institutions. One suspects that a parliamentary approved version of the TEF would simply be a rebranded version of the Sunday Times league table.

As with their previous set of run ins with Jo Johnson, the Lords might chose negotiate a compromise solution during the coming ‘ping pong’ between the two Houses. One possibility might be the formation of some form of independent oversight of TEF, which would have the power to reject the executive’s proposals for the exercise if it felt it lack rigour. This could involve a broad range of stakeholders and independent pedagogical experts committed to making TEF the best it can be, and provide advice and input to the hard-working officials tasked with making the incredible machine run smoothly.

There’s a case to be made for better and more thorough scrutiny of the ins and outs of TEF in order to further refine and improve it, and free it from the whims of the executive. But fully Politicising the exercise (with a very capital P) could make things much, much worse.

I’m assuming that the Lords who oppose TEF are being careful with their language. As the Conservative manifesto contained the words: “we will introduce a framework to recognise universities offering the highest teaching quality” then the concept can’t be overturned in the Lords.

The detail however, and certainly the link to fees, are fair game.

The TEF is a weird thing; a creature of planning departments and senior management teams. Maybe it will move into the world of learning and teaching strategies, curriculum reviews and staff development schemes, but while it is stuck with the weird proxies I bet most attention is being placed on data analysis rather than improvements to learning.

@Mike if you have the Salisbury Convention in mind, this (a) applies only regarding votes on the bill at second or third reading in the Lords, (b) applies only to bills named in the manifesto (it is arguable as to whether it applies to individual policy initiatives, but as only the TEF fee link requires legislation and this was not in the manifesto this is perhaps moot), and (c) may indeed not apply to Theresa May’s government, which was not elected based on a manifesto.

This is a suitably wonky Lord’s Library note on the various issues http://www.parliament.uk/documents/lords-library/hllsalisburydoctrine.pdf