The Teaching Excellence Framework could have a seismic impact on the reputations of British universities, both for good and for ill. As effectively a government-sponsored evaluation, its Gold, Silver, and Bronze awards could be stuck with institutions for up to three years.

The list of outcomes and panel judgements released today were given to Wonkhe under embargo on Wednesday morning. We did not receive the underlying data until this morning, and there will be plenty more to glean from that.

Nonetheless, there is plenty to say about the headline results, which include some shocks (though different ones, depending on how you define them), some insights into how the process has worked (or perhaps not worked), and reminded us to look ahead to the future of TEF.

Less disruptive than you think

Much of the media coverage will focus on how three Russell Group universities, most notably LSE, have been awarded a Bronze. Several other prestigious institutions may also be unhappy about ‘only’ being awarded Silver. Indeed, the much criticised benchmarking element of the exercise was intended to upset previous assumptions about high-quality institutions, and be a fairer game for newer institutions that typically have an intake of much less privileged students.

Yet an early look at the awards ranked by entry tariffs (as used in the Guardian League Table, and so excluding a number of small and specialist institutions) suggests that the ‘upset’ to the traditional hierarchy has been limited, at best. It seems as if Gold awards may be concentrated amongst the highest tariff institutions, even if some are still to be found in the middle and lower tariff groups. The average Guardian entry tariff score (again, noting that this is incomplete data) of all Gold winners is 152, for Silver it’s 132, and for Bronze it’s 125. The ‘big hitting’ Bronze awards for LSE, Southampton, Liverpool, and SOAS, are the exceptions rather than the rule.

Frankly, given what we know about the available data and benchmarks, this is surprising. An speedy examination of the provider submissions suggests that a couple more Russell Group universities may have narrowly escaped Bronze, while a couple more may have only just edged a Gold. We will only be able to work out for certain once we’ve had a chance to run through the underlying data.

Success for the arts and specialists

Small and specialist institutions also appear to have performed very well. Specialist providers winning Gold range from the Arts University Bournemouth to the Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts, the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama to the Royal Veterinary College, and many more such as Harper Adams University, Bishop Grosseteste University, the Conservatoire for Dance and Drama, Rose Bruford College and the Royal College of Music. GuildHE, the representative body for small and specialist higher education providers, had eleven of its thirty-nine members awarded Gold.

All this is particularly good news for arts institutions, who may have been disheartened by last week’s LEO data showing relatively weak salary outcomes in many Creative Arts and Design courses. It goes to show (as does LSE’s Bronze) that a strong TEF performance can contrast strongly with absolute graduate salary outcomes.

An even spread? Not for colleges

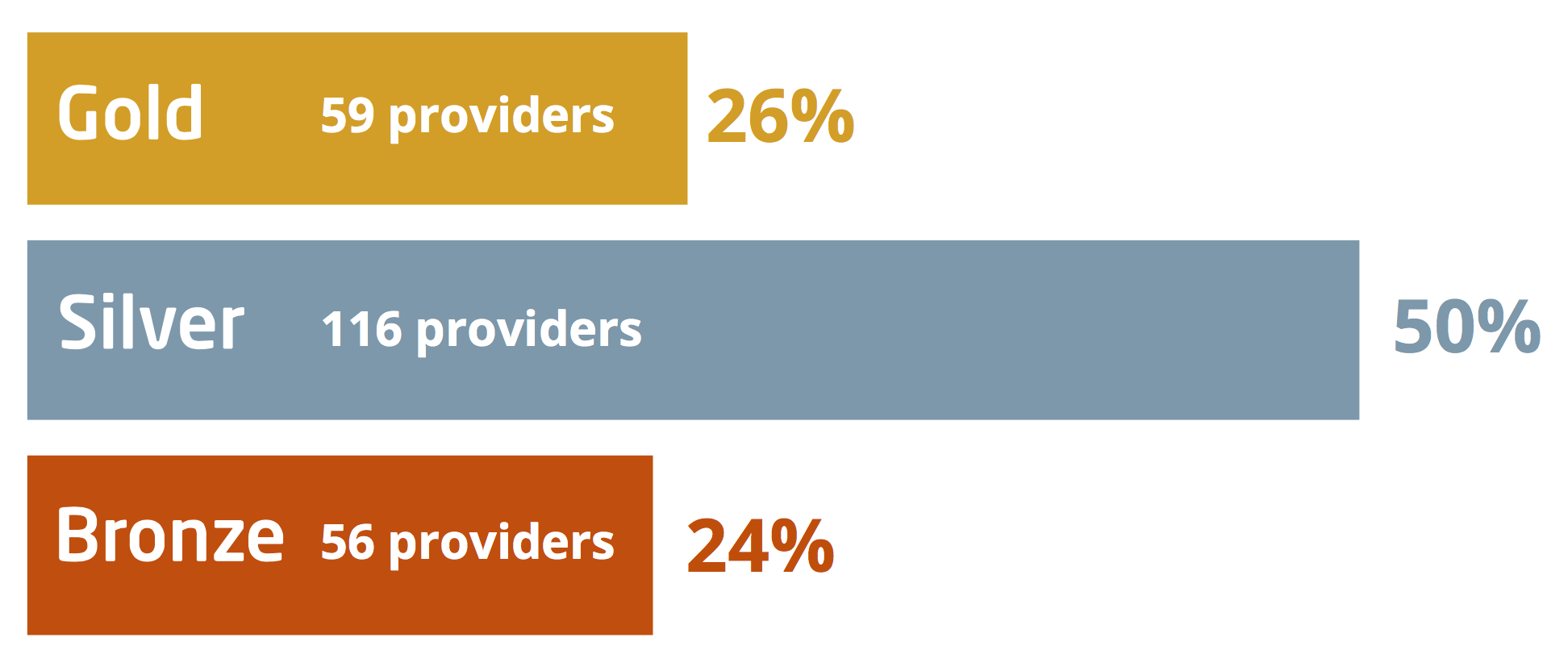

As expected, roughly half of all entrants in TEF have received a Silver outcome, with roughly a quarter each receiving Gold and Bronze. This is nearly consistent with HEFCE’s guidance issued last year, but there is a slightly higher proportion of Gold awards, and slightly smaller proportion of Silver awards, than was suggested by the pure ‘flagging’ of the metrics. This may be due to the addition in the final results of provisional awards for those providers whose metrics were not in sufficient quantity for a full award.

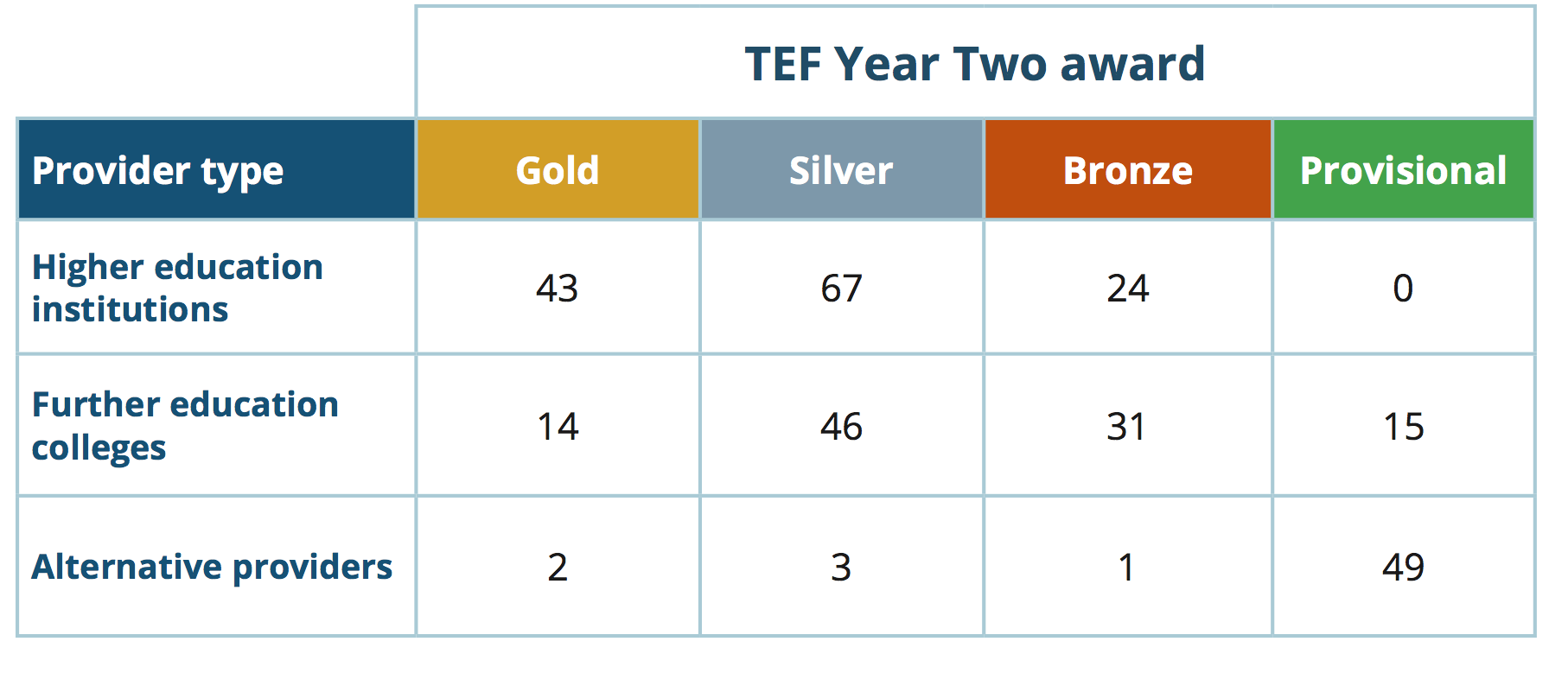

When we break this down, the split in awards varies a great deal between higher education institutions and further education colleges. 32% of higher education institutions achieved Gold, 50% Silver, and 18% Bronze.

However, 34% of further education colleges received a Bronze award. This disparity must raise some questions about the extent to which colleges had the resources to devote to the exercise, particularly their written submissions. But it will take a look at the underlying data to better understand why colleges have, on the whole, struggled.

Sins of omission

As we covered back in February, there was an interesting subplot about which institutions, particularly in England and Wales, had chosen not to participate in this year’s TEF. It appears that – other than the Open University – there have been no high profile higher education provider omissions in England at least. St Mary’s University Twickenham, who just snuck in after the original deadline thanks to DfE’s largesse, got Silver.

Outside England, however, there are some interesting cases of universities that quietly declined to participate. In Wales, Aberystwyth and and the University of South Wales both absented themselves. Neither Queen’s University Belfast nor the University of Ulster decided to take part in Northern Ireland. And in Scotland, there were several known and vocal absentees such as the University of Edinburgh. Still, five Scottish universities did chose to participate – all based on the east coast – and winning three Gold awards and two Silver.

London and the regions

Looking for a highly ranked university but not sure where to start? Try the East Midlands, where seven of eight higher education providers were awarded Gold. However, be warier about London, where Imperial College London was the only non-specialist institution to get Gold. Other regions roughly mirror the spread of awards across the UK as a whole.

Written submissions (or something else…) mattered

This is written before we’ve seen the underlying data or the provider submissions themselves. However, it is clear both from what we know about the available metrics, and also looking at the panel judgements, that some written submissions might have been critical in bumping up some institutions from Bronze to Silver, and others from Silver to Gold.

The HEFCE guidance stated the following:

“The likelihood of the initial hypotheses being maintained after the additional evidence in the provider submission is considered will increase commensurately with the number of positive or negative flags on core metrics. That is, the more clear-cut performance is against the core metrics, the less likely it is that the initial hypothesis will change in either direction in light of the further evidence.”

Some panel judgements suggest that institutions may have been ‘let off’ for ‘negative flags’ on some core metrics, but that their written submission had addressed these issues either “partially”, “fully”, “largely” or “effectively”. It is heavily implicit that this means that some institutions with a negative flag have won Gold (a change from the initial hypothesis according to the HEFCE guidance) and that some with two negative flags have won Silver (which would also be a change from the initial hypothesis). Performance in split metrics may also have been important here.

No challenges to results?

There were rumours going into the process that one or two institutions were already preparing to appeal against their results or even to try request a judicial review. Madeleine Atkins, Chief Executive of HEFCE, stated at yesterday’s press conference that she has not received any indications that institutions will be appealing their results, but watch this space. The deadline to submit a notice of intention to appeal to HEFCE is 12 noon on June 27th.

Plenty still to play for

Today’s TEF outcomes are by no means the final say that this exercise will have on the fate of higher education institutions. There is still a great deal to play for and many things to bear in mind.

Firstly, these results will not be linked to university fee levels for some years. Institutions in England merely have to participate to receive their year-on-year inflationary fee increase until at least 2020. At the rate we’re going, there’s a chance that TEF may never be linked to incremental fee levels, and thus take on a very different raison d’etre.

Secondly, though TEF awards are valid for three years. Institutions can re-enter next year, but there is little reason why those with Gold would jeopardise their rating. This means that TEF year’s three and four will be pretty subdued affairs, allowing the government and the Office for Students to refine the exercise and pilot new aspects of it. In many ways, this year’s TEF is only a taster.

What could these changes look like? Well, the government is now required by the Higher Education and Research Act, as a result of lobbying from the Lords, to commission an independent review of TEF by the end of 2019. The review could make big recommendations about the robustness of metrics, use of ‘medals’ for outcomes, and the place of the written submission.

However, the government has stated its intention to introduce a subject-level TEF exercise. The pilots will begin next year, but as we’ve noted, making this work will be phenomenally complicated. Finally, we know that in the long-run the government hopes to introduce a TEF for taught postgraduate courses backed by the newly available loans, but this appears to have fallen down the list of priorities.

For the most comprehensive coverage of the Teaching Excellence Framework, follow Wonkhe’s TEF hashtag here.